In the desolate expanse of northeastern Mongolia’s steppe, far removed from the grand palaces and bustling metropolises known to dominate medieval East Asian history, an extraordinary archaeological discovery is rewriting how historians and scientists understand life on the fringes of one of the region’s great empires. Archaeologists working at Site 23, a remote garrison outpost strategically positioned along the sprawling defensive wall of the Liao Empire, have uncovered a remarkably rich zoological deposit that offers rare, vivid insight into everyday existence along this medieval frontier.

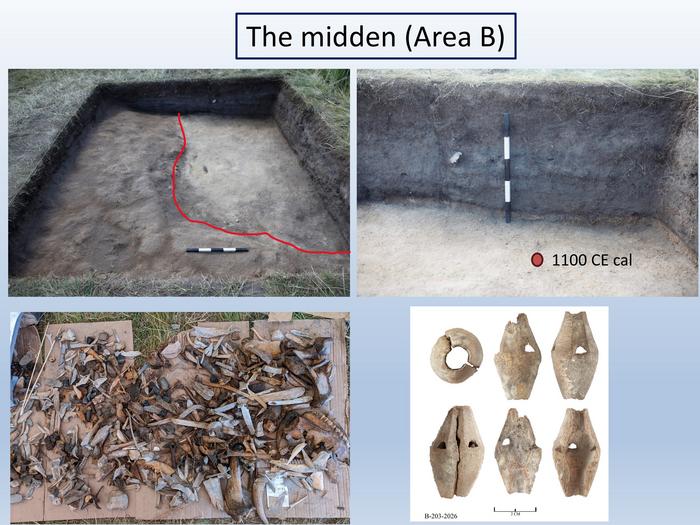

This discovery centers on a remarkably well-preserved midden—a refuse heap—that dates back to approximately 1050 CE, situated within a vast fortification system erected by the Khitan people, the semi-nomadic rulers of the Liao dynasty who controlled large swaths of northern China and Mongolia between 916 and 1125 CE. The long-wall system, extending some 4,000 kilometers in length, remains one of the least understood components of medieval Chinese defensive architecture, largely overshadowed by grander constructions such as the Great Wall. Unlike the imperial records that focus heavily on court rituals and military campaigns, the garbage pile at Site 23 narrates a nuanced story of survival, subsistence, and social dynamics far from the capital’s gilded halls.

Led by doctoral candidate Tikvah Steiner from the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, under the guidance of Professors Gideon Shelach-Lavi and Rivka Rabinovich, this study harnesses zooarchaeological techniques to analyze over 7,000 animal bones meticulously recovered from the midden. The detailed bone analysis illuminates the modalities of life endured by soldiers and possibly their families or auxiliary staff, painting a complex tableau of self-sufficiency. Unlike simple military outposts supplied solely by a central authority, this garrison appears to have operated as an adaptive, resourceful community managing livestock, exploiting wild fauna, and crafting tools and ornaments from bone.

The faunal assemblage reveals a predominance of domesticated species such as sheep, goats, horses, and dogs, alongside wild species including gazelles and mustelids, and even aquatic resources such as catfish. The presence of neonatal remains, particularly lambs and puppies, may indicate a severe environmental stressor—possibly a late spring freeze—that significantly impacted animal survival and, by extension, human subsistence strategies. Such climatic challenges resonate with historical accounts from the final century of the Liao Empire, a period punctuated by environmental adversity and sociopolitical strain.

Cut marks, burn marks, and marrow extraction evidence on the bones provide further indication of complex butchery practices and dietary adaptations. The identification of cattle phalanges deliberately split to access marrow underscores a meticulous use of available resources, while worked bones fashioned into tools and decorative whistling arrows highlight cultural individuality and craftsmanship. These finds disrupt the notion that borderlands were mere buffer zones, instead revealing pockets of cultural vitality operating on the empire’s margins.

The garrison’s economy revolved mainly around pastoralism, with sheep and goats supplying meat, milk, and materials such as wool and hide. Horse breeding further exemplifies the militarized nature of the outpost, critical for communication and warfare on the expansive steppe. However, hunting wild gazelles and mustelids supplemented the diet, while seasonal fishing on local waterways added important protein sources. This diversified subsistence strategy reflects an adaptive economy attuned to local ecological conditions—a vital consideration for sustaining a remote settlement under harsh and fluctuating environmental circumstances.

Importantly, the archaeological data bridges a significant gap in the historical record, which remains silent on the daily life and resilience of frontline inhabitants. The grand narrative of the Liao dynasty’s courtly ambitions and conquests largely omits these border communities, who nonetheless bore the brunt of frontier hardships. Through scientific analysis, these animal bones emerge as silent witnesses, their taphonomy and spatial context offering a form of testimony to human endurance, tacit knowledge, and adaptation amid isolation.

The implications of this research extend beyond the Liao Empire, offering comparative insights into frontier survival across empires, from the Roman limes in Europe to the Great Wall of China. It underscores the universal challenges faced by communities living on the edge of imperial domains—negotiating limited resources, fluctuating supply lines, and climatic volatility to maintain their livelihoods. This study exemplifies the power of interdisciplinary approaches, wherein archaeological science complements historical scholarship to render a fuller, more textured picture of past societies.

Furthermore, the assemblage at Site 23 challenges entrenched historiographical paradigms that privilege elite experiences and monumental architecture over quotidian realities. By foregrounding zooarchaeology, the study unlocks an otherwise invisible narrative about social organization, economic choices, and cultural expression embedded in everyday refuse. It emphasizes how material remains, often discarded and overlooked, can profoundly reshape our understanding of empire and frontier dynamics.

In sum, the ongoing research at Site 23 transforms archaeological midden into a vibrant archive of life on the periphery of the Liao empire. It reveals a community not solely defined by military obligations but characterized by a dynamic synthesis of herding, hunting, craftsmanship, and environmental negotiation. As such, it invites scholars and the public alike to reconsider medieval frontier zones as spaces of intricate human interaction and adaptation, rather than mere margins of imperial history.

Subject of Research: People

Article Title: Subsistence and survival along the medieval long-wall system of northern China and Mongolia: A zooarchaeological and historical perspective

News Publication Date: 4-Jun-2025

Web References: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2025.100639

Image Credits: Photo Credit – Tal Rogovski

Keywords: Historical archaeology, Archaeological periods, Archaeological sites, Archaeology, Cultural anthropology, Animal fossils