NEW YORK, NY — What makes the oldfield mouse steadfastly monogamous throughout its life while its closest rodent relatives are promiscuous? The answer may be a previously unknown hormone-generating cell, according to a new study published online today in Nature from scientists at Columbia’s Zuckerman Institute.

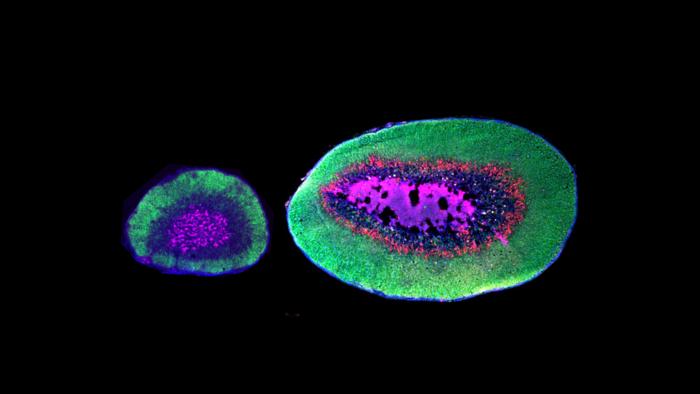

Credit: Bendesky lab/Columbia’s Zuckerman Institute

NEW YORK, NY — What makes the oldfield mouse steadfastly monogamous throughout its life while its closest rodent relatives are promiscuous? The answer may be a previously unknown hormone-generating cell, according to a new study published online today in Nature from scientists at Columbia’s Zuckerman Institute.

“The hormone from these cells was actually first discovered in humans many decades ago, but nobody really knew what it did,” said Andrés Bendesky, MD, PhD, a principal investigator at Columbia’s Zuckerman Institute. “We’ve discovered that it can promote nurturing in mice, which gives us an idea of what it might be doing in humans.”

The new study investigated two species of mice. One is the most abundant mammal in North America — the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), which ranges from Alaska to Central America. The other, the oldfield mouse (Peromyscus polionotus), lives in Florida and Georgia, and is a bit smaller, weighing in at roughly 13 grams compared with the deer mouse’s 18 grams.

More than 100 years of previous research has shown that the mice species behave in strikingly different ways. Whereas the deer mouse is promiscuous — even a single litter of pups can have four different fathers — the oldfield mouse mates for life.

However, prior work also suggested these species are evolutionary siblings, based on similarities in their skulls, teeth and other anatomical features, as well as their genetics. To find out why these close mouse relatives behave so differently, the scientists examined their adrenal glands.

“This pair of organs, located in the abdomen, produces many hormones important for behavior,” said Dr. Bendesky, who is also an assistant professor of ecology, evolution and environmental biology at Columbia University. “These include stress hormones such as adrenaline, but also a number of sex hormones.”

The adrenal glands of these mice proved startlingly different in size. In adults, the adrenals of the monogamous mice are roughly six times heavier than those of promiscuous mice (after adjusting for differences in the body weight between the species).

“This extraordinary difference in the size of an internal organ between such closely related species is unprecedented,” Dr. Bendesky said.

Genetic analysis of the adrenal cells revealed that one gene, Akr1c18, saw far more activity in the monogamous mice than in the promiscuous rodents. The enzyme this gene encodes helps create a little-studied hormone known as 20⍺-OHP, which is also found in humans and other mammals.

The researchers observed that increasing 20⍺-OHP hormone boosted nurturing behavior in both mouse species. For instance, 17 percent of the promiscuous mice who were given the hormone groomed their pups and brought them back to their nests, whereas none behaved this way if not given the hormone.

“This marks the first time we found anything that could increase parental care in the promiscuous group,” Dr. Bendesky said.

Normally these glands are divided into three zones. But the scientists discovered that the adrenals of the monogamous mice possessed a fourth zone.

“We called this the zona inaudita, which is Latin for ‘previously unheard-of zone,’ because no one has ever observed this type of cell in another animal,” said Natalie Niepoth, PhD, a co-first author on the study who is now a senior scientist at Regeneron.

In zona inaudita cells, the researchers found that 194 genes, including Akr1c18, were far more active compared with the same genes in other adrenal cells. Their analyses also identified key genes underlying the development and function of the zona inaudita in the oldfield mice.

This completely unheard-of structure apparently evolved rapidly. Genetic mutations accumulate in genomes at roughly predictable rates over time. By measuring the number of mutations distinguishing these species, the scientists estimated this novel cell type evolved within the past 20,000 years, “which is just an eyeblink when it comes to evolution,” Dr. Bendesky said.

Much remains uncertain about what drives the evolution of monogamous behavior. One argument suggests that monogamy can increase the chances that parents will cooperate to care for their offspring, since fathers are more confident the young are theirs. This kind of teamwork can improve the chances that the progeny will survive, especially when resources are limited, Dr. Bendesky said. The newly found adrenal cells promote parenting behavior typical of monogamy, the researchers noted.

The new findings could provide insights when it comes to parenting behavior and challenges in humans, Dr. Niepoth suggested. For example, in mice, 20⍺-OHP is often converted into a compound very similar to the molecule allopregnanolone, which naturally occurs in humans and has been approved by the FDA as a drug to help treat the postpartum depression that people often experience after childbirth, Dr. Bendesky said.

“I hope that our study motivates further investigation into the link between 20⍺-OHP and parenting in humans,” said Jennifer R. Merritt, PhD, a co-first author on the study and postdoctoral researcher in the Bendesky lab.. “We have so much to learn about the role this hormone plays in human parental behavior.”

###

The paper, “Evolution of a novel adrenal cell type that promotes parental care,” was published online in Nature on May 15, 2024.

The full list of authors includes Natalie Niepoth, Jennifer R. Merritt, Michelle Uminski, Emily Lei, Victoria S. Esquibies, Ina B. Bando, Kimberly Hernandez, Christoph Gebhardt, Sarah A. Wacker, Stefano Lutzu, Asmita Poudel, Kiran K. Soma, Stephanie Rudolph and Andres Bendesky.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Journal

Nature

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Animals

Article Title

Evolution of a novel adrenal cell type that promotes parental care

Article Publication Date

15-May-2024

COI Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.