New archaeological research is shedding unprecedented light on the origins and domestication processes of a native tuber, the Four Corners potato (Solanum jamesii), across the Colorado Plateau. Spearheaded by the University of Utah and published in PLOS ONE, this study challenges long-held assumptions about Indigenous agricultural practices in the American Southwest by providing robust evidence that early Native peoples not only harvested but also intentionally transported, cultivated, and potentially domesticated S. jamesii as far back as 10,000 years ago.

The Four Corners potato has been a cultural, nutritional, and medicinal cornerstone for Indigenous communities across the region for millennia. However, the extent and mechanisms by which these communities domesticated the plant remained obscured. Prior genetic studies hinted at anthropogenic influence by revealing the tuber’s transplantation well beyond its native ecological niche. Now, this monumental study amplifies those findings by analyzing 401 ancient stone tools—metates and manos—unearthed from 14 key archaeological sites spanning the natural and extended anthropogenic range of S. jamesii.

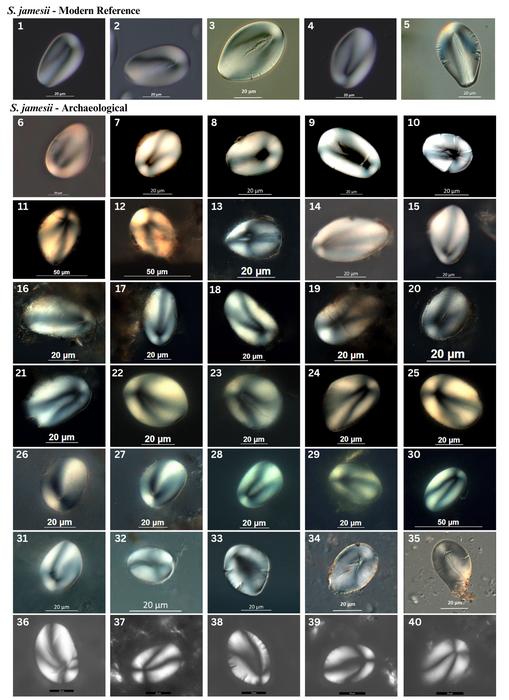

Central to this research is the microscopic identification of starch granules embedded in the crevices of these food-processing implements. These granules serve as molecular fossils, preserving unequivocal evidence of plant processing. Excavation of the starch residues from these millennia-old tools demanded meticulous laboratory techniques developed over a decade to isolate and differentiate S. jamesii starch from other local flora. The results reveal consistent use of this tuber in nine archaeological sites, with several documenting continuous usage dating back to the Paleoindian period, establishing a timeline for active cultivation.

One of the most striking revelations from this research is the definition of the ‘anthropogenic range’ for S. jamesii—a band of the Colorado Plateau where Indigenous populations actively transported and cultivated this tuber. This anthropogenic corridor includes significant sites such as North Creek Shelter in southern Utah, Long House in southwest Colorado, and Pueblo Bonito in northwest New Mexico. Notably, these areas also sustain modern wild populations of S. jamesii, underscoring an ecological legacy of millennia-old anthropogenic influences on plant distribution and diversity.

The plant ecology perspective contributed by co-author Bruce Pavlik points to observable shifts in plant traits within this anthropogenic range. These alterations include enhanced freezing tolerance, prolonged tuber dormancy, and improved sprouting vigor—functional characteristics signaling early stages of artificial selection. Such phenotypic variations strongly hint at directed human intervention in the plant’s life cycle, suggesting that early cultivators engineered the potato’s biology to fit environmental and subsistence needs.

From an anthropological vantage, this study breaks critical ground in decolonizing narratives around Southwestern agriculture that have traditionally emphasized crop introductions from Mesoamerica—namely maize, beans, and squash—while overlooking Indigenous impact on native flora. Integrating archaeological starch analyses with ethnographic interviews, researchers document Indigenous knowledge systems that continue to regard S. jamesii not merely as a food source but as an integral participant in spiritual and cultural practices. Diné and Hopi elders’ accounts authenticate oral traditions describing the potato’s preparation, cultivation, and ceremonial uses, preserving these plant-human relationships into present times.

The use of metates and manos to prepare this tuber marks a technological innovation adapted specifically for extracting starch-rich nutrients essential for survival in a semi-arid environment. These grinding stones, recognizable by their polished and smoothed surfaces, provided a mechanism to release starch granules from the tough tuber tissues while simultaneously recording human subsistence practices in the microscopic traces left behind. The quantification of starch residues on each tool offers a proxy measure for the intensity and frequency of potato processing, painting a nuanced picture of ancient dietary patterns.

Strikingly, this research also reveals social distinctions in botanical expertise within Indigenous communities. Interviews highlight gendered knowledge transmission: women demonstrated active, practical familiarity with S. jamesii’s preparation and use, including employing glésh—specialized white clay—to mitigate the tuber’s natural bitterness. Men, by contrast, referenced the potato in passive terms, indicating shifting cultural roles regarding food procurement and preparation. This gendered disparity reflects broader themes of kinship, land stewardship, and cultural heritage embedded within agricultural systems.

Nutritionally, S. jamesii stands as a remarkable food resource relative to domesticated potatoes elsewhere, boasting triple the protein and double the caloric content of commercial red potatoes, alongside essential minerals and dietary fiber. Such nutrient density would have positioned the Four Corners potato as a vital staple aiding human survival and resilience in the region’s challenging environments, augmenting other foraged or cultivated resources.

Importantly, this work contradicts entrenched biases that questioned Indigenous innovation in native crop domestication, presenting multidisciplinary evidence—from starch residue archaeology and population genetics to ethnobotany and cultural anthropology—that collectively reveals the subtle yet profound human-nature relationships shaping Southwestern food systems over thousands of years. It also highlights ongoing struggles faced by Indigenous communities to regain access to traditional land and plant resources amid contemporary political and environmental challenges, underscoring the need for collaborative stewardship that honors cultural and ecological continuities.

Looking forward, the research team aims to decode the genomic signatures underpinning these phenotypic modifications in S. jamesii populations, striving to identify hallmark genetic markers of artificial selection that could definitively confirm full domestication. Such insights would further cement the Four Corners potato’s status as a native domesticate and enrich our understanding of early agricultural pathways outside Old World and Mesoamerican centers of domestication.

This landmark study exemplifies how combining advanced scientific methods—such as microscopic starch analysis—with Indigenous knowledge and ecological research provides a transformative lens on the deep history of human-plant co-evolution. By illuminating the ancient legacy of the Four Corners potato, researchers are rewriting the agricultural narrative of North America, celebrating Indigenous ingenuity in shaping the landscapes and foodways that persist today.

Subject of Research: Not applicable

Article Title: Ancient use and long-distance transport of the Four Corners potato (Solanum jamesii) across the Colorado Plateau: Implications for early stages of domestication

News Publication Date: 21-Jan-2026

Web References:

PLOS ONE article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0335671

University of Utah Genetics Study: https://attheu.utah.edu/facultystaff/genetics-reveal-ancient-trade-routes-of-four-corners-potato/

Co-Indigenous Management Bears Ears: https://attheu.utah.edu/facultystaff/co-indigenous-management-bears-ears/

References:

Louderback, L., Wilks, S., Joyce, K., Rickett, S., Bamberg, J., del Rio, A., Pavlik, B., Wilson, C. (2026). Ancient use and long-distance transport of the Four Corners potato (Solanum jamesii) across the Colorado Plateau: Implications for early stages of domestication. PLOS ONE.

Image Credits: Louderback et al., (2026) PLOS ONE

Keywords:

Crop domestication, Anthropology, Archaeological sites, Ethnobotany, Ethnography, Indigenous peoples, Agriculture, Farming, Horticulture, Genetics