As the global crisis of plastic pollution intensifies, a groundbreaking study led by scientists at Tulane University sheds new light on the ecological threats plastics pose to marine environments worldwide. This comprehensive investigation represents the first global-scale ecological risk assessment of marine plastic pollution, meticulously mapping not simply where plastics accumulate but where they inflict the greatest harm across oceanic ecosystems. Moving beyond the visible “garbage patches,” the study reveals that the most vulnerable areas are often those where plastics intersect with dense marine biodiversity and existing pollutants, underscoring that even regions with moderate plastic presence may experience significant ecological degradation.

Published in the prestigious journal Nature Sustainability, this pioneering work introduces an innovative framework that evaluates plastic pollution’s multi-pathway impacts on marine life. It examines four critical modes of ecological harm: ingestion of plastic debris by marine organisms, entanglement hazards posed by abandoned fishing gear commonly known as ghost gear, the role of plastics as vectors transporting hazardous pollutants through marine food webs, and the leaching of toxic chemicals as plastics degrade over time. By quantifying these intertwined risk pathways, the study offers a holistic portrait of plastic’s ecological footprint across global oceans.

Yanxu Zhang, associate professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Tulane’s School of Science and Engineering and the study’s lead author, emphasizes the knowledge gap this research addresses. “While the presence of plastic pollution in the ocean is universally acknowledged, the intricate ways it endangers marine ecosystems through diverse biological interactions have remained elusive,” Zhang explains. The research team’s goal was to systematically unravel these complex interactions, using cutting-edge computational techniques to integrate disparate datasets and generate a spatially explicit risk assessment that could inform targeted mitigation efforts.

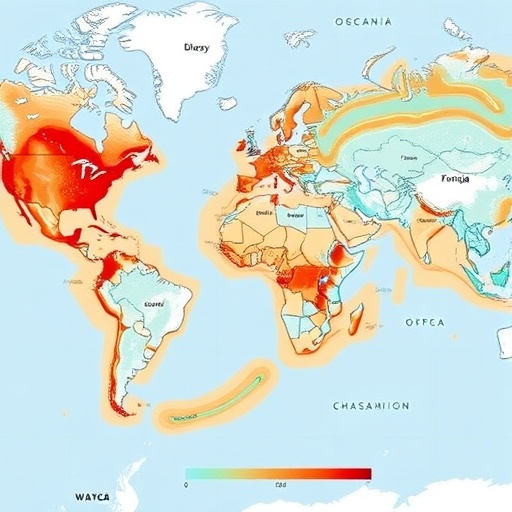

Central to the methodology was the integration of multiple global data models detailing the distribution of ocean plastics, the spatial ranges of marine species, and the global prevalence of toxic pollutants. This interdisciplinary synthesis utilized advanced ecological modeling and machine learning algorithms to predict spatial hotspots where ecological risks from plastic pollution converge. The resultant ecological risk maps identify critical zones where plastics’ harmful effects are most acute, providing a data-driven foundation for prioritizing conservation and cleanup operations beyond areas characterized solely by high plastic density.

Contrary to conventional assumptions that plastic pollution risk corresponds directly with plastic concentration, the findings highlight a more nuanced reality. High-risk zones include mid-latitude regions of the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans, coastal waters of East Asia, and parts of the northern Indian Ocean. In many of these areas, nutrient-rich waters support prolific marine life, heightening vulnerability to ingestion and entanglement risks even when plastic concentrations are not highest. This result challenges policymakers to think beyond the visible accumulation of debris and address ecological sensitivity and pollutant synergy when strategizing marine protection.

A particularly grave hazard identified is the prevalence of “ghost gear” – abandoned fishing apparatus including gillnets, traps, fishing lines, and trawl nets – which poses severe entanglement risks to marine fauna. These derelict materials remain active threats long after being cast aside, ensnaring fish, mammals, and sea turtles with devastating ecological consequences. The study underscores coastal areas adjacent to intensive fishing zones as epicenters of ghost gear impacts, calling for improved waste management and retrieval programs within commercial fisheries.

Moreover, the research illuminates plastics’ insidious role as vectors for toxic contaminants, effectively acting as “conveyor belts” that introduce and magnify hazardous substances within marine food webs. Two substances of particular concern are methylmercury, a potent neurotoxin, and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), one of the notorious “forever chemicals.” Both bioaccumulate through trophic levels and threaten human health via seafood consumption. The spatial overlap between plastic debris contaminated with such pollutants and areas with concentrated marine fauna creates ecological risk hotspots with serious implications for ecosystem and public health.

Looking toward the future, the team employed predictive modeling to simulate scenarios reflecting various global plastic waste management trajectories. The projections are sobering: in the absence of intensified global interventions, the risk of marine organisms ingesting plastics could surge by more than threefold by the year 2060. However, the models also provide hope, indicating that proactive, coordinated efforts to reduce plastic input and enhance municipal and industrial waste processing – particularly in rapidly industrializing nations – can substantially mitigate these escalating threats.

Zhang stresses the timeliness and significance of these findings. “As the international community negotiates a global treaty aimed at curbing plastic pollution, our study provides critical scientific grounding. Our ecological risk maps pinpoint where cleanup and policy measures will be most effective, enabling scarce resources to be allocated strategically.” The research’s integration of ecological, chemical, and spatial data offers a replicable model for future assessments of anthropogenic impacts on marine environments.

This international collaboration spans multiple leading institutions, including Nanjing University and South China University of Technology in China, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego in the United States, Concordia University in Canada, and the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences in New Zealand. Their collective expertise bridged oceanography, ecology, environmental chemistry, and computational modeling, reflecting the multidisciplinary approach essential for tackling complex environmental crises.

In sum, this landmark study redefines how the scientific community and policymakers confront marine plastic pollution, advocating for risk-based management that acknowledges the multifaceted and location-specific nature of plastic-related ecological harm. It compels an urgent reevaluation of current practices and provides actionable insights to safeguard oceanic biodiversity, ecosystem functionality, and, ultimately, human well-being against one of the 21st century’s most pervasive environmental hazards.

Subject of Research: Ecological risk assessment of marine plastic pollution

Article Title: Ecological risk assessment of marine plastic pollution

News Publication Date: 2-Sep-2025

Web References:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-025-01620-x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01620-x

Keywords: Pollution, Water pollution, Environmental sciences, Marine ecology, Conservation ecology, Conservation priorities, Ecological restoration, Ecosystem management, Marine conservation, Conservation policies, Ecological modeling, Ecosystem services, Environmental impact assessments, Natural resources management, Wildlife management, Applied ecology, Earth sciences, Oceanography, Planet Earth