Beneath the serene surface of Gan Ha-Shelosha National Park, a groundbreaking archaeological discovery has emerged that promises to reshape our understanding of medieval industry in the Holy Land. A team led by Professor Amos Frumkin from the Institute of Earth Sciences at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has uncovered an intricate network of subterranean water tunnels hewn directly into the soft tufa rock of the Nahal ‘Amal streambed. These remarkable tunnels, dating back to the 13th to 15th centuries CE during the Mamluk period, provide compelling evidence of a water-powered sugar industry that flourished in the arid southern Levant.

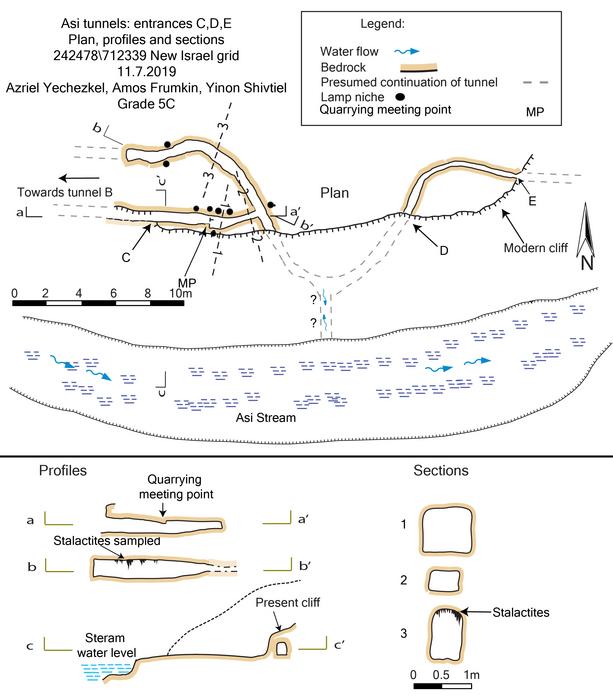

The tunnels, once concealed beneath centuries of sediment and modern development, were revealed through recent construction activity. Researchers identified five parallel shafts exposed by excavations, prompting detailed surveys and hydrological analyses. Unlike the open aqueducts common to the Mediterranean world’s hydraulic systems, these tunnels functioned as enclosed channels strategically designed to harness brackish spring water, reflecting a sophisticated adaptation to the unique geologic and climatic constraints of the Bet She’an Valley. Rather than merely distributing irrigation water, the channels appear to have converted the kinetic energy of flowing water into mechanical power.

By applying uranium–thorium dating techniques to stalactites that formed shortly after the tunnels’ creation, researchers have dated the construction to the late Mamluk era — approximately the 14th to 15th centuries CE. This timeframe aligns closely with historical records that highlight the economic significance of sugarcane cultivation and exportation in the eastern Mediterranean during Mamluk rule. Sugar production required complex water management for irrigation and mechanical crushing, demands met ingeniously by this subterranean network.

The hydraulic design of the tunnels is remarkable in its precision. Subtle gradients within the channels optimized water flow to drive horizontal paddle wheels, an innovative water-powered mechanical solution that turned massive millstones used to crush sugarcane. This engineering feat indicates advanced knowledge of fluid dynamics and mechanical principles within the medieval Levantine context. Excavated wear marks and flow traces within the tunnels, along with the tunnels’ configuration, affirm their primary role in powering sugar mills rather than conventional flour milling installations.

Further archaeological evidence corroborates this interpretation. Among artifacts unearthed downstream is a Mamluk-era oil lamp, temporally anchoring the site within the broader industrial landscape of the period. The presence of such objects emphasizes the integration of this water infrastructure within a thriving network of production and trade that connected the fertile Bet She’an Valley with the expansive Mediterranean sugar markets.

Over subsequent centuries, the original sugar mills underwent transformation. During the Ottoman period, many were repurposed as flour mills, reflecting shifting economic priorities and adaptive reuse of water management infrastructure. This transition underscores the dynamic interplay between environment, technology, and socioeconomic change, demonstrating the tunnels’ lasting significance as pivotal hydraulic assets adjusted to evolving local needs.

The discovery of the Nahal ‘Amal tunnels challenges enduring assumptions that technological innovation in the medieval Levant was limited by environmental scarcity. Instead, it reveals an industrious and pragmatic approach by Mamluk engineers who leveraged natural resources to generate sustainable mechanical power under challenging conditions. Their ability to convert brackish spring water—a resource previously considered suboptimal for irrigation—into a source of reliable energy signifies a nuanced understanding of hydrogeology and mechanical engineering.

From an industrial archaeology perspective, this find bridges multiple scientific disciplines: geology, hydrology, archaeology, and economic history. It vividly illustrates how the physical landscape was manipulated not just for agricultural sustenance but also for industrial productivity, expanding our perception of medieval technological capabilities in the region. The tunnels highlight a sophisticated integration of natural and human systems designed for optimal resource utilization.

Moreover, the use of subterranean water channels represents a strategic innovation distinct from the well-documented open aqueduct systems prevalent elsewhere in the Mediterranean. Encasing the flowing water within rock-carved channels protected the resource from evaporation and contamination in an arid climate, enhancing efficiency and reliability. This design decision illuminates an advanced environmental adaptation rarely documented in medieval hydraulic engineering.

Professor Frumkin emphasizes that these tunnels should be understood as more than mere industrial remnants; they symbolize a broader societal investment in economic infrastructure and resilience. By harnessing the ingenuity of water management, the Mamluks extended their influence beyond military conquests into the realms of commerce and technology, sustaining their empire’s prosperity through effective natural resource control.

This research not only illuminates an engineering milestone but also invites reexamination of historical narratives that have marginalized the Levant’s technological heritage during the Middle Ages. As the team continues to analyze the tunnels and associated artifacts, they anticipate further revelations about the production techniques, labor systems, and trade networks supported by this water-powered sugar industry.

In sum, the submerged water tunnels of Nahal ‘Amal serve as a powerful testament to medieval innovation, revealing how environmental challenges were met with technical creativity to support a vibrant industrial economy. These findings enrich our understanding of the Mamluk era’s economic infrastructure and highlight the complex interdependencies between human ingenuity, natural resources, and historic trade that shaped the medieval Mediterranean world.

Subject of Research: Not applicable

Article Title: Water tunnels at Nahal ‘Amal (Israel): evidence of a water-based sugar industry in the Mamluk period?

News Publication Date: 16-Oct-2025

Web References:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12685-025-00368-7

Image Credits: Azriel Yechezkel, Amos Frumkin, Yinon Shivtiel

Keywords: Archaeology, Water resources