Reconstructing Ancient Identities: Unveiling Europe’s Earliest Victory Celebrations Through Multi-Isotope Analysis

A groundbreaking study published in Science Advances offers unprecedented insights into the lives and violent deaths of individuals buried in mass graves dating back to the late Middle Neolithic period in Europe. By harnessing cutting-edge multi-isotope analytical techniques, researchers have shed new light on prehistoric conflict, challenging long-held assumptions about the nature and cultural significance of violence in ancestral societies.

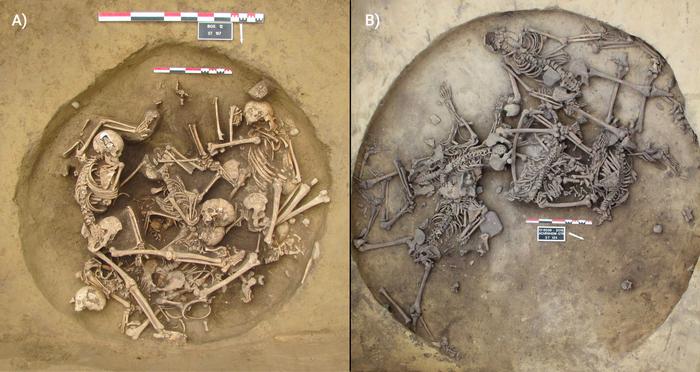

The research focuses on two enigmatic burial sites in the Alsace region of northeastern France — notably Achenheim and Bergheim — where archaeologists uncovered complex assemblages of human remains characterized by extraordinary patterns of trauma and postmortem manipulation. These sites, dated to approximately 4300–4150 BCE, hold key evidence that violence during this era was far from random; instead, it was orchestrated with ritualistic precision and symbolic intent.

Excavations revealed skeletons bearing signs of extreme and repetitive blunt-force trauma, brutally inflicted in ways exceeding what would be necessary merely to kill. Alongside these complete skeletons, archaeologists found pits containing only severed left upper limbs, meticulously detached and deposited. This unusual combination of complete skeletons and isolated trophy limbs defies conventional interpretations of Neolithic violence, which often presume indiscriminate massacres or pragmatic executions.

To decode this complex mortuary phenomenon, the international research team employed multi-isotope analyses, examining isotopic signatures within teeth and bone collagen from the victims. These signatures—particularly strontium and oxygen isotopes—act as geographic and dietary tracers, revealing not only individual life histories but also their movement across landscapes. The approach enabled scientists to differentiate locals from outsiders with remarkable precision.

The isotopic data pointed to a striking dichotomy between the individuals whose limbs were severed and those subjected to full skeleton burials. The detached limbs displayed local isotopic values, suggesting these were warriors native to the region, likely killed in battle. In contrast, the complete bodies bore isotopic signatures consistent with origins outside the immediate area and exhibited indicators of higher physiological stress earlier in life, hinting at a history of displacement or captivity.

This dual pattern supports the hypothesis that these Neolithic death assemblages represent the aftermath of structured martial victory celebrations rather than mere episodes of warfare or extermination. In this interpretation, local combatants killed in battle were dismembered, with their limbs taken as trophies to display martial success and dominance. Meanwhile, non-local captives—possibly vanquished enemies or rival communities—were subjected to painful, theatrical executions designed to humiliate and reinforce the victor’s social cohesion.

Such practices imply that violence in Neolithic Europe had far-reaching social and cultural dimensions beyond physical conflict. The mortuary treatment of these victims functioned as political theater, a performative assertion of power woven into the fabric of early communal identity. It was a ritual that communicated messages of dominance, control, and memory, embedding combat experience within collective social narratives.

Professor Rick Schulting, a senior author of the study from the University of Oxford, emphasizes the broader implications: “These findings reveal a sophisticated strategy in which violence was ritualized and instrumentalized not simply as pragmatic warfare but as a spectacle imbued with social meaning. The Neolithic communities engaged in acts that expressed dominance, forged alliances, and shaped cultural memories through carefully staged post-conflict ceremonies.”

The detailed isotopic reconstructions further amplify our understanding of the victims’ life courses. Individuals with full skeletons showed signatures reflecting varied diets and elevated physiological stress markers—possibly evidence of nutritional deficiencies or chronic hardship—consistent with the hardships faced by captives or marginalized groups. Conversely, the trophy limbs belonged to individuals with isotopic profiles indicating residency in the local environment, reinforcing their status as community members and primary combatants.

This dual identity narrative challenges simplified models of prehistoric violence, which often viewed Neolithic conflict through the lens of generalized, random aggression or resource-driven conflict alone. Instead, the study invites us to reconsider this period as one marked by intricate social dynamics, where ritualized violence played a pivotal role in maintaining societal structures and identities.

Environmental and archaeological context support this interpretation. The Alsace region during the late Neolithic was a cultural crossroads, experiencing significant social transformations as farming communities expanded and interacted. These tensions likely sparked conflict but also created opportunities for ritual performances that helped regulate group boundaries and hierarchies.

Additionally, the research team’s use of multi-isotope biography represents a methodological advancement in archaeology. By combining isotopic data derived from multiple elements—strontium, oxygen, carbon, and nitrogen—the team reconstructed nuanced lifetime mobility, diet, and stress patterns for individuals long deceased. Such integrative approaches promise to revolutionize our capacity to interpret the social lives of ancient peoples.

The collaborative effort, funded by a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions grant and involving institutions across Europe, reflects a multidisciplinary approach essential to unraveling complex prehistoric behaviors. It involved expertise from archaeology, chemistry, anthropology, and bioarchaeology, bridging data and theory to produce a holistic picture.

Ultimately, this study contributes a crucial dimension to the human story, illuminating how acts of violence in deep prehistory were enmeshed with cultural meanings, identity formation, and social memory. It demonstrates that even some of the earliest known episodes of organized conflict were not merely destructive but also constructive in shaping emerging social orders.

As techniques like multi-isotope analysis become more refined, they will continue to unveil hidden narratives from ancient human remains, transforming fragmentary bones into vivid stories of migration, conflict, and human experience. This research sets a new benchmark in reconstructing the complex interplay of life, death, and ritual in early European societies.

Subject of Research: People

Article Title: Multi-isotope biographies and identities of victims of martial victory celebrations in Neolithic Europe

News Publication Date: 20-Aug-2025

Web References:

Multi-isotope biographies and identities of victims of martial victory celebrations in Neolithic Europe (DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv3162)

Image Credits:

A: pit 157 from Bergheim (credit: F. Chenal); B: pit 124 from Achenheim (credit: P. Lefranc).

Keywords: Archaeology, Human remains