Do children have regular bedtimes and do parents enforce strict screen time policies? And do parents take their children to museums so that they can learn from an early age? Or is everyday life more about having fun together, without clear rules and any ambition to ‘develop’ children in any particular way?

Credit: University of Copenhagen

Do children have regular bedtimes and do parents enforce strict screen time policies? And do parents take their children to museums so that they can learn from an early age? Or is everyday life more about having fun together, without clear rules and any ambition to ‘develop’ children in any particular way?

Family life can be lived in many different ways, and what children bring with them from the home environment has a substantial impact on their opportunities and development later in life.

A new study from the Department of Sociology, University of Copenhagen, and VIVE – The Danish Center for Social Science Research now offers a research-based typology of how the everyday lives of Danish families with young children can be grouped into four types of family learning environments. Four types that might influence children in very different ways.

“Learning environments are not just about playing spelling games with children,” says Professor Mads Meier Jæger from the Department of Sociology, co-author of the study.

“Our study shows that there are big differences in the learning environments in which Danish children grow up, but also that it is possible to categorise them into different general types. Consequently, the study provides a comprehensive picture of children’s learning environments and how individual dimensions of these environments interact,” he says.

Level of activity, daily structure and learning environments

The study derives four types of family learning environments from rich data collected from 44 Danish families with children aged 3-6. Using a custom digital diary app, parents documented their family life with text, photos, audio and video over a period of 12 weeks. Parents were also interviewed.

From the data collected, the authors of the study outlined six dimensions particularly salient in characterising learning environments: Family activities, emotional climate, organisation of everyday life, social networks, expectations and values, and out-of-home care.

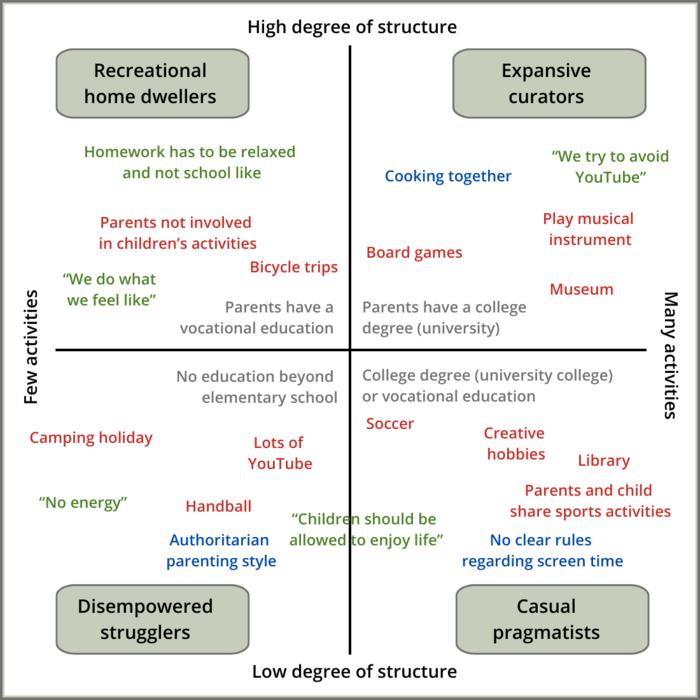

The six dimensions were then condensed into four typical learning environments on the basis of the level (and type) of family activities and the degree of structure in everyday life (see figure as well as brief description below). The diagram illustrates each learning environment by means of specific activities and statements.

According to Mads Meier Jæger, one of the strengths of the typology is that it is based on the activity level and everyday organisation of families. Previous research has confirmed that these are key dimensions in children’s learning. In addition, the model shows a relationship between learning environments and parental education. This is consistent with research suggesting that education is the single strongest dimension of socioeconomic status.

The four categories should not be interpreted too rigidly. Many families may resemble more than one learning environment. Nor does the study say how many families belong to each of the four types. It is only the association between different activities, attitudes and underlying social factors that the researchers have mapped.

New Scandinavian perspective

Nevertheless, the categories provide a new, Scandinavian perspective on children’s learning environments, as the study also includes children’s school, institutional and leisure lives. The ‘casual pragmatists’ and ‘recreational home dwellers’ are very much products of the Scandinavian welfare regime and reflect other forms of inequality than those in economic and social typically of Anglo-Saxon countries.

“For example, children whose parents have vocational education and jobs are not socially disadvantaged. Parents have jobs and resources, but their focus is not on academic stimulation and children acquiring higher education. These families simply have other priorities,” Mads Meier Jæger explains.

This way, the new typology provides a richer picture of how many individual parts of family life together create a family learning environment. This is important, Mads Meier Jæger says.

“In Denmark, we also have social inequality and lack of mobility in some dimensions. If we want to tackle these challenges, we need to understand where inequality originates. Our study tries to provide some answers by taking a more holistic approach.

The four learning environments in brief

(See also the attached simplified figure (Figure 1) and the study’s original figure (Figure 2) with more examples)

Expansive curators tend to have a college/university degree and ensure that children have many educational and stimulating activities inside and outside the home (e.g. word games, music lessons and museum visits). The emotional climate is safe and everyday life is organised, for example with regular bedtimes and strict rules regarding children’s use of screens. Parents are very active in their children’s lives outside the home, which they see as an extension of their in-house learning environment.

Casual pragmatists tend to have a medium level of higher education, such as a bachelor’s degree or perhaps a vocational education. As with the ‘expansive curators’, they also engage in many and varied activities, but typically with less focus on cognitive stimulation and under less supervision. Overall, daily life, while still emotionally stable, is more loosely structured in terms of meals, bedtimes, etc.

Recreational home dwellers tend to have a vocational education or similar. Like ‘expansive curators’, daily life is structured. However, family activities tend to take place in or near the home, and parents emphasise recreation rather than deliberately stimulating children. Spending time in the garden is preferred to visiting a museum, and watching Eurovision for kids is more common than playing the piano. The type of education children receive is less important if they receive one.

Disempowered strugglers have weakest social networks, few financial resources and sometimes no formal education. Families participate in few activities and family life is often characterised by uncertainty and lack of structure and, unlike the other three groups, the emotional climate can be unstable. Parents are rarely involved in their children’s lives outside the home.

Facts about the study

The article ‘Family learning environments in Scandinavia: dimensions, types and socioeconomic profiles’ has been published in the British Journal of Sociology of Education.

The authors of the article are Mads Meier Jæger, Department of Sociology/UCPH, Katrine Syppli Kohl, Saxo Institute/UCPH, and Jens-Peter Thomsen, Sofie Henze-Pedersen, Kirstine Karmsteen and Rasmus Henriksen Klokker, all from VIVE – The Danish Center for Social Science Research.

The study is based on extensive analyses of qualitative data from 44 Danish families with children aged 3-6 years, including the families’ electronic diaries, supplemented by a systematic literature review. The families were selected to cover a range of educational levels but are not representative of all Danish families.

The study is part of the project ‘Learning environments in Danish families and their importance for children’s development’, which is supported by the A.P. Møller Foundation and primarily anchored at VIVE.

Journal

British Journal of Sociology of Education

Method of Research

Observational study

Subject of Research

People

Article Title

Family learning environments in Scandinavia: dimensions, types and socioeconomic profiles

Article Publication Date

5-Mar-2024