Astronomers have captured what appears to be a snapshot of a massive collision of giant asteroids in Beta Pictoris, a neighboring star system known for its early age and tumultuous planet-forming activity.

Credit: Roberto Molar Candanosa/Johns Hopkins University, with Beta Pictoris concept art by Lynette Cook/NASA.

Astronomers have captured what appears to be a snapshot of a massive collision of giant asteroids in Beta Pictoris, a neighboring star system known for its early age and tumultuous planet-forming activity.

The observations spotlight the volatile processes that shape star systems like our own, offering a unique glimpse into the primordial stages of planetary formation.

“Beta Pictoris is at an age when planet formation in the terrestrial planet zone is still ongoing through giant asteroid collisions, so what we could be seeing here is basically how rocky planets and other bodies are forming in real time,” said Christine Chen, a Johns Hopkins University astronomer who led the research.

The insights will be presented today at the 244th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Madison, Wisconsin.

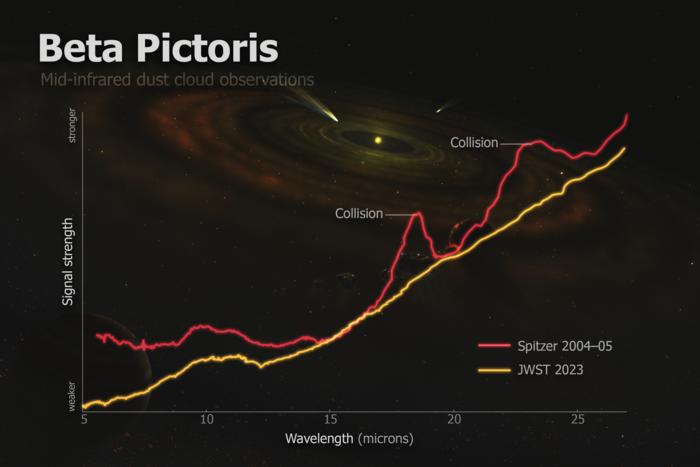

Chen’s team spotted significant changes in the energy signatures emitted by dust grains around Beta Pictoris by comparing new data from the James Webb Space Telescope with observations by the Spitzer Space Telescope from 2004 and 2005. With Webb’s detailed measurements, the team tracked the dust particles’ composition and size in the exact area previously analyzed by Spitzer.

Focusing on heat emitted by crystalline silicates—minerals commonly found around young stars as well as on Earth and other celestial bodies—the scientists found no traces of the particles previously seen in 2004–05. This suggests a cataclysmic collision occurred among asteroids and other objects about 20 years ago, pulverizing the bodies into fine dust particles smaller than pollen or powdered sugar, Chen said.

“We think all that dust is what we saw initially in the Spitzer data from 2004 and 2005,” said Chen, who is also an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute. “With Webb’s new data, the best explanation we have is that, in fact, we witnessed the aftermath of an infrequent, cataclysmic event between large asteroid-size bodies, marking a complete change in our understanding of this star system.”

The new data suggests dust that was dispersed outward by radiation from the system’s central star is no longer detectable, Chen said. Initially, dust near the star heated up and emitted thermal radiation that Spitzer’s instruments identified. Now, dust that cooled off as it moved far away from the star no longer emits those thermal features.

When Spitzer collected the earlier data, scientists assumed something like small bodies grinding down would stir and replenish the dust steadily over time. But Webb’s new observations show the dust disappeared and was not replaced. The amount of dust kicked up is about 100,000 times the size of the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs, Chen said.

Beta Pictoris, located about 63 light years from Earth, has long been a focal point for astronomers because of its proximity and random processes where collisions, space weathering, and other planet-making factors will dictate the system’s fate.

At only 20 million years—compared to our 4.5-billion-year-old solar system—Beta Pictoris is at a key age where giant planets have formed but terrestrial planets might still be developing. It has at least two known gas giants, Beta Pic b and c, which also influence the surrounding dust and debris.

“The question we are trying to contextualize is whether this whole process of terrestrial and giant planet formation is common or rare, and the even more basic question: Are planetary systems like the solar system that rare?” said co-author Kadin Worthen, a doctoral student in astrophysics at Johns Hopkins. “We’re basically trying to understand how weird or average we are.”

The new insights also underscore the unmatched capability of the Webb telescope to unveil the intricacies of exoplanets and star systems, the team reports. They offer key clues into how the architectures of other solar systems resemble ours and will likely deepen scientists’ understanding of how early turmoil influences planets’ atmospheres, water content, and other key aspects of habitability.

“Most discoveries by JWST come from things the telescope has detected directly,” said co-author Cicero Lu, a former Johns Hopkins doctoral student in astrophysics. “In this case, the story is a little different because our results come from what JWST did not see.”

Other authors are Yiwei Chai and Alexis Li of Johns Hopkins; David R. Law, B.A. Sargent, G.C. Sloan, Julien H. Girard, Dean C. Hines, Marshall Perrin and Laurent Pueyo of the Space Telescope Science Institute; Carey M. Lisse of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory; Dan M. Watson of the University of Rochester; Jens Kammerer of the European Southern Observatory; Isabel Rebollido of the European Space Agency; and Christopher Stark of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

The research was supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration under Grant No. 80NSSC22K1752.

Journalists registered for the meeting can attend the presentation in person or virtually on Monday, June 10 at 10:15 a.m. Central Standard Time. Nonregistrants may watch the press conference on the AAS Press Office YouTube channel but will be unable to ask questions.

Method of Research

Observational study