Across the vast landscape of cognitive neuroscience, visuomotor adaptation stands as a fundamental process that enables individuals to finely tune their motor actions in response to changing visual inputs. This dynamic recalibration of motor output based on sensory feedback is critical not only for everyday activities such as reaching and grasping but also plays a vital role in rehabilitation and skill acquisition. Yet, despite the extensive research on motor learning mechanisms, a compelling question arises: to what extent are these mechanisms truly universal? A groundbreaking study led by Assistant Professor Chiharu Yamada at Waseda University, Tokyo, ventures into this uncharted territory, uncovering how deeply embedded cultural cognitive biases silently shape the explicit strategies underpinning visuomotor adaptation.

Visuomotor learning is characterized by the brain’s ability to adjust limb movements through feedback integration, enhancing the precision with which motor actions align with sensory goals. Historically, motor adaptation has been conceptualized as a combination of implicit and explicit processes. Implicit components reflect automatic adjustments made without conscious awareness, whereas explicit components involve deliberate strategy use and cognitive evaluation. Conventional models have often treated these explicit strategies as global constants across populations. However, mounting evidence from cultural psychology suggests significant variability in cognitive styles, decision-making, and bias formation, hinting that cultural context might recalibrate the explicit dimensions of motor learning in ways not previously appreciated.

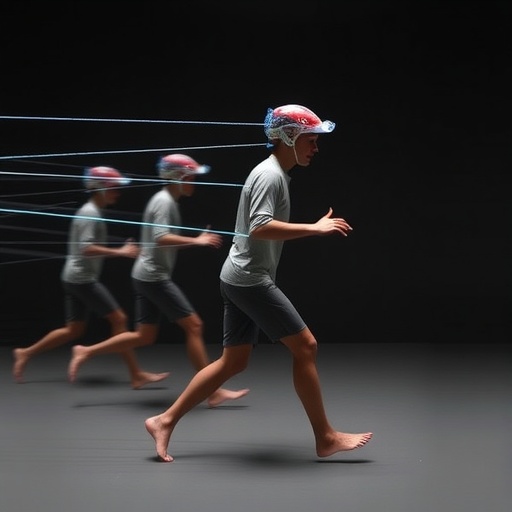

The study spearheaded by Yamada and colleagues was meticulously designed to probe this intersection of culture and cognition within the strictures of an experimental aiming task paradigm. This research involved 48 university students divided equally between two culturally and geographically distinct groups: Japanese and Norwegian participants. Each individual engaged in a computer-based task requiring rapid and accurate angular adjustments to target a circle among eight possible locations on a display, using a trackball mouse. Crucially, visual feedback was systematically rotated, necessitating visuomotor recalibration. This setup allowed the researchers to dissect the nuanced changes in strategy participants employed to overcome feedback perturbations.

Surprisingly, the study unveiled that while both Japanese and Norwegian participants exhibited comparable overall task performance in terms of endpoint accuracy and aftereffects, marked differences emerged in their explicit aiming strategies. Japanese participants demonstrated a tendency to aim at positions noticeably offset from the actual target, indicating a broader explicit exploratory strategy. Moreover, they adjusted their aiming directions more frequently—even after successfully hitting a target—contrasting with their Norwegian counterparts who showed greater aiming consistency post-success. This behavioral pattern implicates an underlying cognitive bias rooted in explicit motor planning, modulated by cultural background.

These findings challenge the longstanding assumption that motor learning adaptation strategies are invariant across populations. Instead, they emphasize that the explicit cognitive components of motor control are susceptible to culturally ingrained cognitive biases. Such biases manifest unconsciously yet shape the manner in which individuals interpret feedback and deploy corrective strategies during motor learning. These results resonate with a broader psychological dialogue on how Eastern and Western cognitive schemas differ, with East Asian cultures exhibiting holistic and context-sensitive cognitive styles, while Western cultures favor analytic and rule-based approaches.

The ramifications of this study extend far beyond theoretical neuroscience and touch upon practical domains such as clinical rehabilitation and athletic training. Traditional rehabilitation paradigms often rely on patient verbal reports and explicit feedback to assess recovery trajectories. If cultural biases influence patients’ reporting styles and explicit adaptation strategies, standardized assessment tools may misinterpret genuine progress or failure. Likewise, in sports science, coaching instructions that assume uniform interpretation may fall short when cross-cultural athletes apply differing explicit strategies, potentially impacting training effectiveness and motor skill acquisition.

Intriguingly, this research beckons a paradigm shift in developing adaptive learning systems, particularly educational technologies that incorporate motor learning algorithms. By integrating cultural dimensions into these systems, designers can achieve more equitable and precise skill assessments, ensuring that adaptive feedback aligns not only with individual performance metrics but also embraces culturally contingent cognitive frameworks. This culturally attuned approach represents a critical leap towards personalized motor learning interventions on a global scale.

Assistant Professor Yamada highlights the critical necessity for researchers and clinicians alike to recalibrate their interpretive frameworks: “Our research highlights the risk of misinterpreting motor learning abilities when explicit strategies are measured without accounting for cultural bias, urging a re-evaluation of assessment tools in global research and clinical contexts.” This statement underscores a broader call to the scientific community to embed cultural sensitivity into experimental design, data interpretation, and therapeutic applications.

The methodological rigor of this investigation amplifies its credibility. The utilization of a controlled visuomotor rotation paradigm with precise measurement of aiming directions offers granular insight into the temporal dynamics of explicit and implicit motor processes. Moreover, the cross-cultural comparative approach, spanning continents and diverse cognitive milieus, sets a precedent for subsequent studies to dissect cultural contributions to neurocognitive functions with greater specificity.

Furthermore, the findings stimulate rich avenues for future research. Probing the neural correlates of these explicit cultural biases through neuroimaging techniques, such as fMRI or EEG, could illuminate the circuitry involved in culturally modulated motor planning. Additionally, expanding participant demographics to include a wider array of cultural backgrounds, age groups, and clinical populations would deepen understanding of the universality versus specificity debate in motor adaptation.

In the educational domain, integrating these insights fosters the design of culturally adaptive training programs that optimize motor skill development. Such innovations could revolutionize how instructors customize learning experiences, balancing implicit automaticity with culturally influenced explicit strategy instruction. This has profound implications for domains ranging from music performance to surgical training where visuomotor adaptation is paramount.

From a theoretical perspective, this research enriches cognitive neuroscience by juxtaposing culture as a dynamic modifier rather than a peripheral variable in cognitive modeling. It demands an interdisciplinary synthesis, blending anthropology, psychology, and neurobiology to construct comprehensive models of human cognition that respect cultural diversity alongside neural commonalities. This holistic vision aligns with the emerging ethos of globally inclusive science.

In summary, the work led by Assistant Professor Chiharu Yamada and collaborators traverses fresh intellectual terrain, revealing that unconscious cultural cognitive biases pervade the explicit processes governing visuomotor adaptation. Importantly, these biases subtly yet decisively influence how individuals consciously strategize motor corrections, a revelation with wide-reaching implications for research, clinical practice, education, and technology design. As the quest to unravel the complexities of motor learning progresses, acknowledging the silent cultural fingerprints embedded within cognitive control stands as a critical milestone on the path toward truly universal neuroscientific principles.

Subject of Research: People

Article Title: Unconscious cultural cognitive biases in explicit processes of visuomotor adaptation

News Publication Date: 2-Jul-2025

Web References: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41539-025-00335-0

References:

Yamada, C., Itaguchi, Y., & Rodríguez-Aranda, C. (2025). Unconscious cultural cognitive biases in explicit processes of visuomotor adaptation. npj Science of Learning. DOI: 10.1038/s41539-025-00335-0

Image Credits: Assistant Professor Chiharu Yamada from Waseda University, Japan

Keywords: Psychological science, Motor development, Cognition, Learning, Neuroscience, Education, Cultural practices, Human behavior, Sports, Cognitive bias