England’s Forgotten First King: Æthelstan’s Groundbreaking Legacy Reclaimed by Scholar Ahead of Historic Anniversaries

A seismic reevaluation of England’s earliest monarchy is stirring the historical landscape as Professor David Woodman from the University of Cambridge unveils a compelling new biography of Æthelstan, the ruler heralded by many as England’s first king. This scholarly work comes at a momentous time, marking the 1,100th anniversary of Æthelstan’s coronation in 925 AD and the subsequent founding of the English kingdom in 927 AD. Woodman’s meticulous research confronts the longstanding marginalization of Æthelstan’s reign and fervently campaigns for his rightful acclaim in public consciousness and academia alike.

Æthelstan’s significance has been obscured through centuries, largely eclipsed by iconic events such as the Battle of Hastings in 1066 or the Magna Carta in 1215. The absence of a contemporary biographer for Æthelstan contrasts sharply with figures like Alfred the Great, whose legacy was bolstered by the Welsh cleric Asser’s detailed chronicles. Moreover, subsequent political narratives favored King Edgar for ecclesiastical reforms, further relegating Æthelstan’s pioneering contributions in governance and culture to historical footnotes. Woodman aims to reverse this trend, spotlighting the intricate fabric of Æthelstan’s political acumen and enduring influence on the English state.

At the core of Æthelstan’s enduring impact lies his unparalleled military leadership, essential to his success in unifying disparate territories under a single realm. His campaigns suppressed Viking settlements entrenched in northern and eastern England, culminating in the pivotal acquisition of York in 927 AD. This conquest effectively incorporated Northumbria into Æthelstan’s dominion, cementing the territorial contours of what would be recognized as England. The strategic brilliance of Æthelstan’s campaigns is underscored by his command over a coalition of Welsh and Scottish kings, compelled to participate in his royal assemblies as tokens of submission, revealing a geopolitically complex and assertive reign.

The Battle of Brunanburh in 937 AD stands as the apotheosis of Æthelstan’s military dominance, where his forces decisively crushed a formidable alliance of Vikings, Scots, and Strathclyde Welsh eager to dismantle his rule. Woodman emphasizes that Brunanburh’s historical importance rivals that of the Battle of Hastings, not least because contemporary chronicles from England, Wales, Ireland, and Scandinavia all document the battle’s carnage and outcome with remarkable unanimity. While the exact location remains debated, Woodman confidently locates the battle at Bromborough on the Wirral, a site whose strategic merits and linguistic roots support his conclusion.

Beyond the battlefield, Æthelstan’s reign heralded a revolutionary transformation in royal governance. Legal documents from his period—particularly the ‘diplomas,’ grants of land issued by the king—are distinguished not only by their formality but also by their literary sophistication. Woodman notes a deliberate evolution in these documents, which during Æthelstan’s rule became elaborate expressions of royal authority, embodying a learned Latin style replete with rhetorical flourishes such as rhyme and alliteration. This enhancement marks a paradigm shift: from mere administrative instruments to potent symbols of centralized power projecting the king’s legitimacy and political vision.

Moreover, the mechanics of Æthelstan’s government exhibit a level of administrative centralization previously unappreciated. The presence of a royal scribe entrusted with overseeing document production, and who consistently accompanied the king and his assembly across the kingdom, signals a systemic strategy to maintain cohesion and assert control. Woodman elucidates how Æthelstan’s governance included the dissemination of law codes to various shires, accompanied by feedback mechanisms that informed subsequent legislative reforms—an early instance of data-driven policy implementation in medieval governance.

Æthelstan’s consolidation of power was not merely a domestic affair but also a deft engagement with broader European politics. While contemporaneous continental realms fragmented with nobles asserting autonomous control, Æthelstan fortified his position by forging dynastic ties through the marriage of his half-sisters into influential continental houses. This diplomatic foresight ensured England’s embeddedness within the intricate matrix of European power relations, underscoring Æthelstan’s role as a forward-looking statesman.

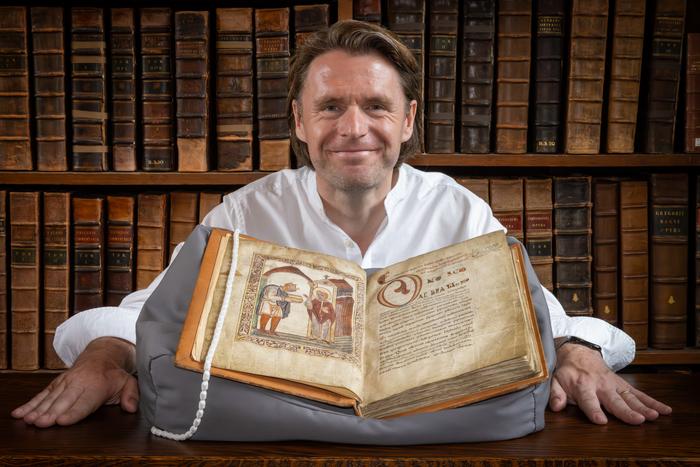

Cultural and religious revitalization further marked Æthelstan’s reign, addressing the decline in learning and ecclesiastical influence that followed Viking devastations of monastic centers. Woodman highlights Æthelstan’s patronage of scholars from across Europe who gathered at his court, nurturing an intellectual renaissance. A key artifact symbolizing this cultural resurgence is the earliest extant portrait of an English monarch, depicting Æthelstan reverently before Saint Cuthbert, preserved in a 10th-century manuscript housed at the Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. This image signals Æthelstan’s strategic efforts to align himself with revered saints and religious institutions to legitimize and advance his rule.

Another poignant piece of evidence comes from the Durham Liber Vitae, a tenth-century manuscript listing individuals associated with the Community of Saint Cuthbert in alternating gold and silver lettering. Remarkably, Æthelstan’s name is inscribed near the manuscript’s beginning, an indication of his prominent status and personal connection with the religious community—a link possibly fostered by those within his retinue during a 934 visit. These religious engagements reveal Æthelstan’s sophisticated use of spiritual patronage as a mechanism of kingship and statecraft.

Professor Woodman’s campaign extends beyond historical reexamination to tangible public recognition. Collaborating with prominent figures including historian-broadcasters Tom Holland and Michael Wood, and under the aegis of Alex Burghart MP, Woodman advocates for commemorative monuments—whether statues, plaques, or portraits—in sites intimately linked with Æthelstan’s legacy: Westminster, Eamont Bridge, and Malmesbury. Such efforts aim to embed Æthelstan’s memory within the national narrative, correcting the historic oversight and celebrating the architect of England’s inception.

Education remains a pivotal frontier in redefining Æthelstan’s stature. Woodman urges the integration of Æthelstan’s story into mainstream school curricula, challenging the predominant focus on post-conquest events. His assertions rest on the premise that understanding the formation of England is equally, if not more, critical than its subsequent conquests, fostering a more nuanced appreciation of medieval state formation and governance.

Æthelstan’s reign, covering less than two decades, witnessed foundational political, military, and cultural innovations that shaped England’s trajectory for centuries. The relative fragmentation following his death in 939 AD has led some historians to question the durability and authenticity of his contributions. However, Woodman rebuts this perspective by emphasizing that the very difficulties that followed highlight the magnitude of Æthelstan’s achievements—he forged a kingdom where none had previously existed, establishing governance principles and a royal identity whose echoes resonate through English history.

This comprehensive reevaluation invites both scholars and the public to reconsider early medieval England, not as a peripheral prelude to the Norman conquest, but as a period marked by sophisticated state-building and visionary leadership. Æthelstan’s story, resurrected through meticulous scholarship and public advocacy, promises to transform the understanding of English origins, placing this forgotten king at the center of the nation’s historical imagination.

Subject of Research: Æthelstan’s reign and his foundational role in the creation of the Kingdom of England

Article Title:

News Publication Date: 2nd September 2025

Web References: https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691249490/the-first-king-of-england

References: Woodman, David. The First King of England: Æthelstan and the Birth of a Kingdom, Princeton University Press, 2025

Image Credits: The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Keywords: Æthelstan, early English monarchy, Battle of Brunanburh, medieval governance, Anglo-Saxon England, royal diplomacy, historical biography, English state formation