In a groundbreaking study published in the International Journal of Anthropology and Ethnology, scholar Y. Gong delves into the intricate development of cartographic representations in ancient China, specifically analyzing the concept of Tianyuan Difang and the evolution of the single-sheet Tianxia Tu before approximately 1600 AD. This research sheds new light on ancient Chinese worldviews and geographical understandings, with implications that resonate far beyond the historical context.

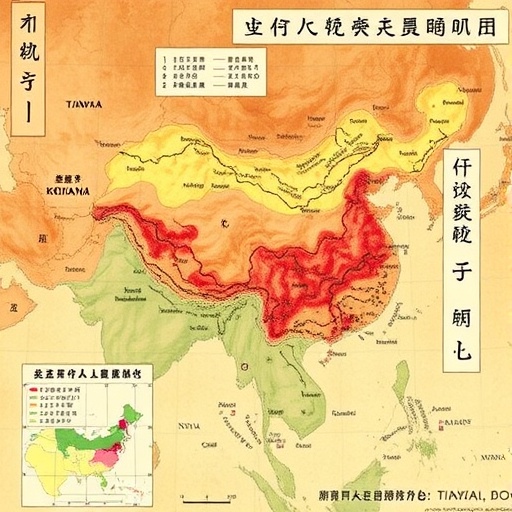

The Tianxia Tu, literally translating to “Map of All Under Heaven,” represents one of the earliest comprehensive attempts to portray the world from a distinctly Chinese perspective. Unlike Western medieval maps that often showed fragmented and religiously inspired geographies, the Tianxia Tu embodies an integrative spatial vision rooted in Chinese cosmology and political ideology. Gong’s work meticulously examines the transition from multi-sheet to single-sheet versions of these maps, highlighting the significance of design shifts and their cultural implications.

Central to Gong’s analysis is the concept of Tianyuan Difang, which can be understood as the “Central Origin Place” or the cosmic center of the world. This idea aligns closely with Chinese philosophical traditions, particularly those stemming from Confucianism and Daoism, that envision the emperor’s realm as the geopolitical and cosmic nucleus. Gong argues that Tianyuan Difang was not only a specific geographical area but also a symbolic notion through which ancient Chinese cartographers framed their spatial interpretations.

Technological advancements in paper production, ink, and printing during the Song and Ming dynasties played a crucial role in enabling the creation of single-sheet maps. These technological innovations democratized geography by allowing maps to be more widely circulated and accessible. Gong carefully analyzes how improvements in medium corresponded with evolving political narratives and administrative needs, particularly regarding frontier management and imperial projection.

From a technical standpoint, Gong’s study emphasizes the cartographic techniques employed in these ancient maps, such as the use of proportional scaling, symbolic representations of mountains and rivers, and hierarchical spatial ordering. These techniques reflect a sophisticated understanding of geography that integrates empirical observation with ideological function. For instance, the representation of borders in the Tianxia Tu served not merely to demarcate space but to assert imperial dominion and cultural hegemony.

What is particularly striking in Gong’s findings is the realization that the Tianxia Tu was much more than a tool for navigation. It operated simultaneously as a map, a political manifesto, and a philosophical text. Its iconography communicates values of order, harmony, and the emperor’s Mandate of Heaven, thus intertwining cartography with governance and cosmology in a uniquely Chinese fashion.

The shift to a single-sheet format also reveals changes in the audience for these maps. While earlier multi-sheet maps were primarily commissioned by scholars and officials, the more compact Tianxia Tu could address a broader segment of society, including merchants and local administrators. This broader dissemination suggests a shift towards a more inclusive conception of spatial awareness, possibly in response to expanding trade and internal migration patterns.

Moreover, Gong contextualizes these transformations within larger global cartographic trends. While European mapmaking during the same period tended toward explorations and continent-wide representations driven by colonial ambitions, Chinese cartography maintained its focus on “All Under Heaven” as a harmonious and hierarchically ordered universe. This divergence underscores differing worldviews and the complex interplay between geography and ideology.

The research also identifies surviving examples of Tianxia Tu maps housed in various museums and archives, analyzing their physical attributes, stylistic differences, and annotations. Gong applies modern digital imaging techniques to decode faded inscriptions and reconstruct coloring schemes, thereby reviving insights into the aesthetic and informational richness of these artifacts.

Gong’s work furthermore probes into the social functions of the Tianxia Tu, suggesting that it operated within rituals and education systems as a mnemonic device and a medium for reinforcing collective identity. In an era before mass literacy, such visual tools were indispensable in encoding knowledge, values, and power structures.

One of the more captivating sections of the study focuses on how these maps managed the representation of borderlands and peripheral regions, which were often contested and culturally diverse. Through cartographic omission or inclusion, mapmakers exercised agency in defining the political landscape, shaping perceptions of belonging and otherness. This plays into larger narratives of pilgrimage, trade, and military campaigns of the time.

In addition to historical and cultural analyses, Gong utilizes geographic information system (GIS) methodologies to digitally overlay historical Tianxia Tu maps with modern geographic data. This innovative approach allows for a spatial understanding of map accuracy, revealing how much was symbolic versus topographically precise. Such interdisciplinary methods demonstrate the potential for blending humanities with technology.

The implications of Gong’s findings extend to modern understandings of cartography as a culturally embedded practice rather than a neutral scientific endeavor. By illustrating how ancient Chinese maps were instruments of ideology and identity, this study invites reconsideration of map-making in all historical contexts, including contemporary ones where geopolitical narratives continue to shape representations of space.

In sum, Gong’s comprehensive exploration of the Tianyuan Difang concept and the evolution of the single-sheet Tianxia Tu not only enriches our comprehension of ancient Chinese cartographic traditions but also contributes to broader discourses on the interrelations between geography, power, and culture. This research is an essential reference point for historians, anthropologists, cartographers, and anyone interested in how humans conceptualize and visualize their world.

Subject of Research: The evolution of ancient Chinese cartography focusing on the concept of Tianyuan Difang and the development of the single-sheet Tianxia Tu maps before circa 1600 AD.

Article Title: The concept of Tianyuan Difang and the evolution of single-sheet Tianxia Tu in ancient China (before around 1600 AD).

Article References:

Gong, Y. The concept of Tianyuan Difang and the evolution of single-sheet Tianxia Tu in ancient China (before around 1600 AD). Int. j. anthropol. ethnol. 9, 3 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41257-025-00126-w

Image Credits: AI Generated

DOI: 10.1186/s41257-025-00126-w (Published 24 February 2025)