In a groundbreaking revelation, an extensive study led by researchers from Aalto University has unveiled a startling discrepancy in global population databases, highlighting a significant underestimation of rural populations worldwide. The findings indicate that these datasets may overlook as much as 53% to 84% of individuals living in rural areas, a shocking statistic that carries profound implications for public policy and resource allocation across both developed and developing nations.

Governments, international organizations, and numerous scholarly investigations lean heavily on global population metrics for various essential functions, including healthcare planning, infrastructure development, epidemiological studies, and disaster management. As these datasets have been foundational to countless decisions, the study arises as a critical call to reassess their accuracy and applicability in real-world scenarios. Josias Láng-Ritter, a postdoctoral researcher at Aalto University, emphasizes the lack of reliable demographic data in understanding rural populations, suggesting that the actual number of individuals residing in these areas is significantly higher than previously documented.

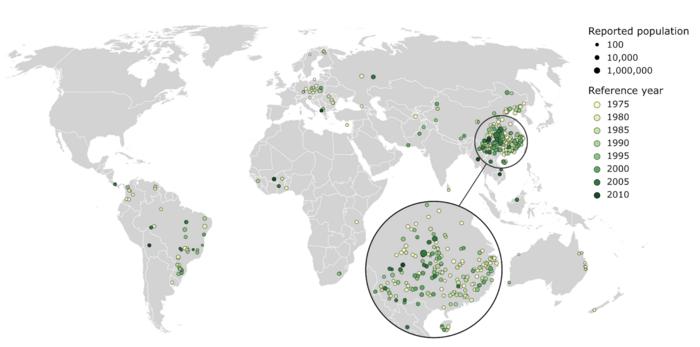

The study scrutinizes the integrity of five widely utilized global population datasets, which rely on census data to divide geographical regions into high-resolution grid cells representing population density. By cross-comparing these datasets with resettlement statistics from over 300 rural dam projects spanning 35 nations, the researchers illustrate the systemic flaws inherent in current population tracking methodologies. Remarkably, they found that even the most recent datasets exhibit substantial inaccuracies, missing substantial portions of rural inhabitants.

The investigation covered data periods ranging from 1975 to 2010, as the availability of dam-related data for subsequent years remained sparse. It was revealed that data from 2010 displayed the least bias, still failing to represent one-third to three-quarters of the actual rural populations documented. Despite advancements in capturing more accurate demographic information over the years, Láng-Ritter asserts the persistence of systemic underrepresentation, suggesting that relying on traditional census methods may not rectify these disparities.

The root causes of these biases appear to emanate from traditional census practices, which are often logistically challenging in rural settings. Sparse populations distributed across vast areas lead to incomplete data collection processes, leaving many individuals uncounted and thus excluded from global datasets. Moreover, many nations lack the financial and infrastructural resources necessary for meticulous demographic compilation, further exacerbating the issue of misrepresented populations.

In contrast, Damian resettlement data sourced from hydropower projects serve as reliable indicators for accurate population counts. The relocation process following dam constructions necessitates meticulous tracking of affected individuals, driven by compensation protocols. This provides an invaluable comparison point for researchers, revealing that local counts often reflect the actual numbers more accurately than the broader datasets that succumb to administrative and geographical biases.

The study’s significant implications extend beyond mere statistics. As approximately 43% of the global population resides in rural regions, the study raises alarms about the overlooked needs of these communities. The resulting misrepresentation could lead to inadequate resource allocation, affecting vital services such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure development within rural environments. Decisions based on flawed demographic information could, therefore, perpetuate inequalities between urban and rural regions.

Given that official estimates from the United Nations and the World Bank draw upon the same national census data informing these datasets, the challenge of accurately representing rural populations gains urgent significance. Lack of reliable data indicates that rural communities are likely to receive insufficient attention in planning initiatives, which could worsen underdevelopment and exacerbate existing disparities.

The team’s findings urge a renewed conversation about the methodologies employed in population data collection. In particular, nations grappling with inadequate local demographics are urged to reconsider their reliance on potentially misleading global datasets. Láng-Ritter highlights the critical need to merge modern technological advancements with traditional data collection methods in a way that accurately reflects the diversity and distribution of populations, thereby ensuring equitable access to services, resources, and policy initiatives.

In high-income countries like Finland, population data can be remarkably reliable, showcasing a model that combines historical records with advancements in digital record-keeping. Finland’s early adoption of digital population records in 1990 exemplifies how technological innovation can enhance the accuracy of demographic statistics. For many nations still struggling to establish reliable census methodologies, however, the path towards digitalizing records may take years and even decades.

As this study reverberates across policy-making circles, it emphasizes the necessity of adapting and improving current population datasets. Failure to address these systemic deficiencies threatens to skew more than just population counts; it jeopardizes the future well-being of rural communities whose voices remain muted in the corridors of power. The call to action is clear: without comprehensive, reliable population data, crafting effective policies to ensure equitable resource distribution becomes an insurmountable challenge.

This research is a pivotal step forward in highlighting and mitigating the biases inherent in global demographic data collection. The implications for future census practices cannot be overstated, as governments and organizations worldwide confront the dual challenges of effective rural representation and accurate demographic planning in an ever-evolving global landscape.

Subject of Research: Global population datasets and their representation of rural populations

Article Title: Global Gridded Population Datasets Systematically Underrepresent Rural Population

News Publication Date: 18-Mar-2025

Web References: Nature Communications

References: Not provided

Image Credits: Credit: Josias Láng-Ritter et. Al / Aalto University

Keywords: Population data, rural populations, Aalto University, census bias, resource allocation, demographic data, global datasets