As climate change intensifies, the relationship between extreme weather events and human migration is growing increasingly complex. A groundbreaking study published on September 3 in Nature Communications sheds new light on how demographic factors such as age and education critically shape migration patterns in response to severe heat waves, droughts, and other climate stressors. Moving beyond simplistic narratives of mass displacement, this research reveals a nuanced picture: some populations are forced to move while others find themselves trapped in place, unable to escape worsening conditions.

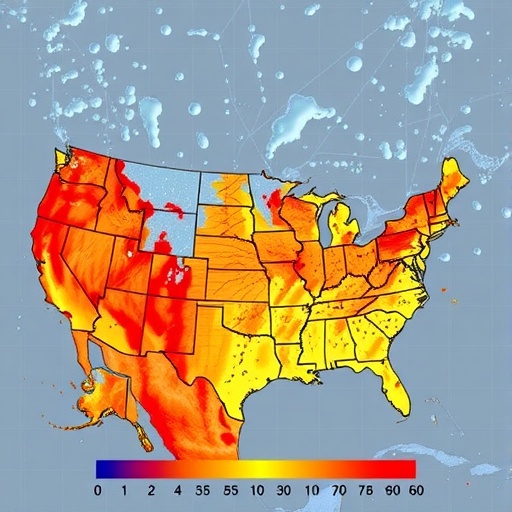

The interdisciplinary team, led by environmental social scientist Hélène Benveniste of Stanford University, analyzed an unprecedented dataset comprising over 125,000 instances of cross-border migration from 168 origin countries to 23 destinations, alongside more than 480,000 internal moves within 71 nations. Each migration event was categorized by variables including migrant age, educational attainment, sex, as well as origin and destination attributes. This granular demographic classification generated 32 distinct groups, which were then correlated with high-resolution climate data such as daily temperature fluctuations and soil moisture levels, key indicators closely tied to agricultural productivity, food security, and human wellbeing.

One of the pivotal revelations of the study is the identification of a “double penalty” phenomenon that disproportionately impacts vulnerable groups. The research illustrates that older adults with lower levels of formal education are more likely to migrate internationally following extreme heat events. Conversely, children under 15 and less-educated individuals often exhibit diminished mobility, constrained by economic and social barriers. This dual disadvantage compounds existing inequalities: those with the fewest resources to adapt in situ are also those who lose migration as a viable survival strategy.

Technically, the team’s model outperforms previous frameworks by incorporating demographic heterogeneity, boosting predictive accuracy of cross-border migration patterns by up to a factor of twelve, and improving within-country migration forecasts by approximately five-fold. Despite this advancement, the study underscores that extreme weather accounts for only a minor fraction—around 1%—of historical international migration variability. This finding emphasizes that human mobility is a multifaceted phenomenon influenced by a constellation of socio-political, economic, and cultural forces transcending climatic stimuli.

The impact of high temperatures manifests differently across migratory contexts and demographic profiles. For example, adults over 45 with basic or no education are more prone to undertaking international migration during heat stress episodes, likely driven by reduced local livelihood viability. In contrast, cross-border movements among those with advanced education remain relatively unaffected by climate variability, suggesting such groups possess either alternative coping mechanisms or less exposure to climate-induced economic shocks.

Within-country migration dynamics appear even more sensitive to baseline climate characteristics. In tropical zones where average temperatures hover near 86°F, a threshold-crossing day above 102°F correlates with a subtle yet measurable uptick—roughly 0.5%—in domestic relocation among highly educated adults. This phenomenon implies that educated individuals in warmer climates may possess greater adaptive capacity and mobility options, enabling them to seek refuge in less affected areas. Meanwhile, residents with minimal schooling in normally arid regions face different pressures: severe and prolonged dry spells generate heightened internal migration, reflecting a stark differentiation in climate responses among socio-educational strata.

Crucially, the research confronts common public and policy discourses that anticipate dramatic mass border surges fueled by climate change. Projecting under a scenario where global mean temperature escalates beyond 2.1°C above pre-industrial baselines, migration rates among older, less educated adults could increase by approximately 25% by the year 2100. However, the model also predicts a contrasting decrease of up to 33% in migration among the youngest and least educated cohorts. These demographic-specific shifts far exceed the moderate 1–5% changes revealed by analyses limited to aggregate population averages, underscoring the necessity of nuanced understanding when forecasting climate-driven mobility.

The study’s methodology deliberately isolates weather-related drivers by holding other migration influencers—such as political instability, economic opportunity, and conflict—constant. By doing so, it isolates a clearer signal of how worsening climate extremes may recalibrate who can move and who remains immobilized. Yet, author Benveniste stresses that real-world future migration outcomes will hinge on an intricate interplay of societal responses, policy interventions, and adaptive strategies that evolve alongside environmental pressures.

From a technical standpoint, the integration of daily climate records with highly disaggregated migration data represents a major methodological innovation enabling richer insights into environmental migration dynamics. Soil moisture measurements, combined with temperature data, serve as critical proxies for assessing impacts on agricultural systems, which in turn influence livelihood stability—a central factor driving migration decisions in lower-income regions. This fine-scale analytical approach addresses long-standing gaps in previous research, which often treated populations as homogenous units reacting uniformly to climatic changes.

The implications for policymaking are profound. By highlighting demographic disparities in climate mobility, the study calls for tailored adaptation strategies that recognize diverse vulnerabilities. It advocates for support mechanisms not only aimed at migrants but crucially those who remain behind—often the most marginalized and climatically vulnerable. Such an inclusive approach is vital for equitable climate resilience, ensuring resource-poor individuals have access to both in-place adaptation and migration options as necessary.

Furthermore, the exposé of a “double penalty” sheds light on the urgent ethical dimensions of climate justice. As climate crises deepen, the global community must confront how systemic inequality restricts mobility pathways for the least empowered, entrenching cycles of vulnerability. The findings suggest that addressing educational inequities and enhancing access to migration resources may be key levers for enabling more adaptive responses to escalating climate shocks.

In conclusion, this landmark study redefines our understanding of climate-induced migration by demonstrating that the story is not merely about how many move, but fundamentally about who moves—and who does not. Through sophisticated demographic and climatic data integration, it reveals that migration in the face of climate stress is a differentiated process shaped by age, education, and local environmental contexts. As the planet warms, these insights are essential for developing informed and just policies that respond to the complexities of human mobility under climate change.

Subject of Research: Climate Change and Human Migration Demographics

Article Title: Global Climate Migration Is a Story of Who and Not Just How Many

News Publication Date: 3-Sep-2025

Web References:

Keywords: Climate Migration, Extreme Weather, Heat Waves, Drought, Demographic Factors, Cross-Border Migration, Internal Displacement, Socioeconomic Vulnerability, Climate Adaptation, Human Mobility, Environmental Social Sciences, Climate Change Impacts