In a groundbreaking revelation that reshapes our understanding of ancient human civilizations in Island Southeast Asia, an extensive archaeological study spearheaded by researchers from the Ateneo de Manila University has unveiled compelling evidence of sophisticated maritime culture dating back over 35,000 years in the Philippine archipelago. This extensive research effort, known as the Mindoro Archaeology Project, offers profound insights into early human migration, technological innovation, and intercultural exchanges across vast maritime domains during the prehistoric period.

The focal point of this research lies in the island of Mindoro, situated in the western Philippines, which, unlike Palawan, was never connected to mainland Southeast Asia by land bridges or ice sheets. This isolation implies that early inhabitants had to master seafaring capabilities to traverse the open sea, an endeavor demanding advanced cognitive and technological skills during the Paleolithic era. These findings challenge long-held assumptions about early human adaptability and maritime proficiency in this part of the world.

Through meticulous excavations on several sites across Mindoro, such as Ilin Island, San Jose, and Sta. Teresa, Magsaysay, the researchers uncovered artifacts and ecological remains including human skeletal fragments, animal bones, shells, and a wide variety of lithic and organic tools that offer a window into the daily lives and survival strategies of these early maritime communities. These discoveries suggest a nuanced understanding of both terrestrial and marine ecosystems that sustained human populations for millennia.

One of the most striking aspects of the findings is the evidence indicating that these ancient communities possessed advanced fishing technologies and skills, targeting predatory open-sea species such as bonito and shark. Catching these fast-moving pelagic fish would have required specialized equipment and seafaring competence, pointing to a sophisticated maritime economy dating back tens of thousands of years. This technological prowess reveals deep knowledge about marine biology as well as seasonal and oceanographic patterns.

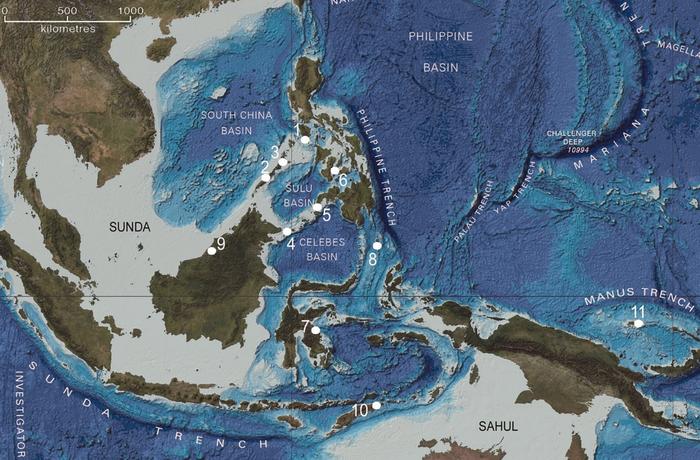

Equally significant is the innovation surrounding the utilization of marine shells as tool-making materials, an uncommon practice in many contemporary Paleolithic cultures. The Mindoro assemblages yielded adzes crafted from giant clam shells (genus Tridacna), dating from approximately 7,000 to 9,000 years ago. These tools closely parallel shell adzes found widely across Island Southeast Asia and as far away as Manus Island in Papua New Guinea, over 3,000 kilometers distant, suggesting a far-reaching network of cultural and technological exchange.

From an anthropological perspective, the team uncovered a 5,000-year-old human grave on Ilin Island, where the interred individual was placed in a carefully flexed or fetal position and covered with limestone slabs. This burial method resonates with practices observed elsewhere in Southeast Asia, pointing to shared ideological frameworks or social constructs that transcended island boundaries. It offers a rare glimpse into the funerary customs and social complexities of prehistoric maritime societies.

The Mindoro Archaeology Project’s findings collectively imply that Mindoro and neighboring Philippine islands were not peripheral or isolated locales in prehistoric times but rather pivotal nodes within an extensive maritime network that connected disparate human groups across Island Southeast Asia. This network facilitated cultural diffusion, technological transmission, and perhaps even social alliances, transforming our view of ancient human interactions from fragmented island groups to a dynamic, interconnected seascape.

Moreover, the presence of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) in Mindoro dating back over 35,000 years situates the Philippine archipelago as a crucial corridor in the broader story of human migration through Southeast Asia and into the Pacific. The chronology and nature of the artifacts suggest a continuous and evolving adaptation to maritime environments rather than episodic occupation, underscoring the importance of seafaring in human evolutionary history.

The shell adzes, in particular, invite fresh discussions about technological convergence and innovation. Their morphology and distribution propose that complex craft traditions were shared or independently developed across vast distances. These tools’ manufacture involved intricate processes of shell selection, shaping, and hafting, reflecting advanced skill sets that would have materialized only through sustained experimentation and knowledge transmission.

Equally transformative is the understanding of subsistence strategies drawn from faunal remains and associated artifacts. The simultaneous exploitation of terrestrial fauna and challenging marine species indicates a diversified and resilient economy, crucial for survival in island ecosystems often characterized by fluctuating resources. This ecological versatility likely played a significant role in enabling human populations to expand and thrive across Island Southeast Asia.

The archaeological narrative emerging from Mindoro also reframes the traditional models that have underpinned prehistoric research in the region. It suggests that movement across the Wallacea region—known for its deep-water barriers—was far more intentional and technologically supported than previously assumed. Therefore, early populations demonstrated remarkable ingenuity in overcoming geographic obstacles, which had profound implications for subsequent human dispersals into Oceania and beyond.

Furthermore, these findings enrich interdisciplinary dialogues between archaeology, anthropology, paleoenvironmental sciences, and maritime studies. They illustrate how integrated research strategies combining excavation, artifact analysis, and environmental reconstruction can illuminate complex prehistoric behaviors otherwise invisible in the ancient record, thus enhancing our comprehension of humanity’s adaptive capacities.

The research team behind this project includes Dr. Alfred F. Pawlik, Dr. Riczar B. Fuentes, and Dr. Tanya Uldin from Ateneo de Manila University’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology, alongside Dr. Marie Grace Pamela G. Faylona from the University of the Philippines – Diliman and other Philippine universities, along with doctoral candidate Trishia Gayle R. Palconit from the University of Ferrara in Italy. Their collaborative efforts epitomize the global nature of contemporary archaeological research, leveraging local expertise and international perspectives to unlock the past.

Publication of these findings in the journal Archaeological Research in Asia marks a milestone in the comprehension of prehistoric maritime cultures within Island Southeast Asia, offering a seminal contribution that will undoubtedly inspire further exploration, debate, and discovery in the field. This work not only bridges significant gaps in the prehistoric record of the Philippines but also compels reassessment of regional maritime development and human migration paradigms worldwide.

Subject of Research: People

Article Title: Philippine islands had technologically advanced maritime culture 35,000 years ago

Web References: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2025.100616

Image Credits: The Mindoro Archaeology Project (Base Map: www.gebco.net, 2014)

Keywords: maritime archaeology, Mindoro, Philippines, seafaring technology, ancient humans, Island Southeast Asia, shell tools, human migration, Stone Age, prehistoric trade networks