In a groundbreaking new study emerging from South Yorkshire in the United Kingdom, researchers have illuminated the nuanced relationship between darkness and criminal activity, pushing the boundaries of our understanding of crime patterns after the sun sets. By analyzing a decade’s worth of comprehensive crime data involving over 34,000 incidents, the research team led by Jim Uttley from the University of Sheffield offers compelling evidence that darkness itself elevates the overall risk of certain types of crimes, though this risk varies significantly according to the kind of offense and the geographic area in question.

The study tackles a longstanding debate within criminology and urban planning that has puzzled policymakers and law enforcement alike: does darkness inherently increase the likelihood of crime, or is the perceived risk merely a product of reduced visibility and public fear? Historically, the prevailing assumption has been that poor lighting conditions facilitate criminal behavior, with many cities investing heavily in street lighting as a crime deterrent. Yet, until now, hard evidence supporting or disproving this premise has been inconsistent and inconclusive.

Uttley and his colleagues approached this question by capitalizing on the unique seasonal variations in daylight throughout the year at specific times of day, which could either fall within daylight or after dark depending on the season. This clever methodological twist allowed the researchers to isolate darkness as an independent variable affecting crime risk, while controlling for other confounding elements such as weather conditions and holiday periods that might influence crime rates.

The results revealed a striking pattern: while the aggregate risk of crime increased after dark, this effect was not uniform across all crime types. Out of fourteen distinct categories of offenses analyzed, only five—burglary, criminal damage, personal robbery, bicycle theft, and vehicle offenses—were found to be significantly more prevalent during nighttime hours. Contrastingly, offenses such as sexual crimes, arson, and shoplifting did not demonstrate a notable increase with darkness.

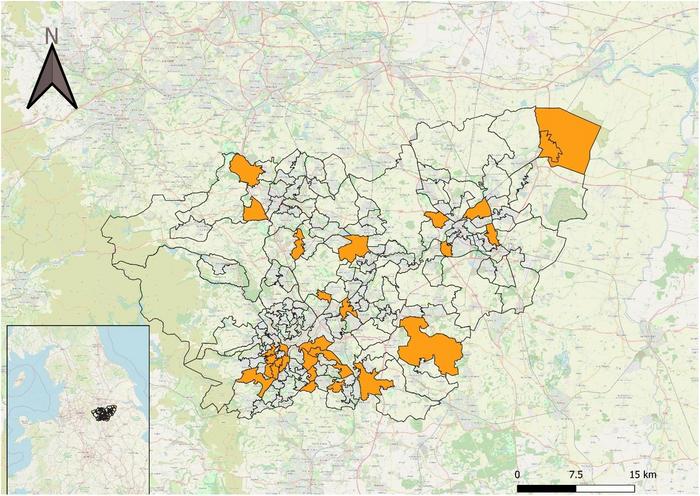

In addition to crime type variations, geographical disparities emerged as a critical factor in the analysis. The risk of crimes after dark was not evenly distributed across neighborhoods within South Yorkshire; instead, it shifted dynamically depending on local characteristics, demonstrating the importance of spatial context in understanding the complex interplay between darkness and crime.

This nuanced finding challenges the oversimplified narrative that darkness uniformly breeds crime and suggests a need for more targeted interventions. While improving street lighting is intuitively appealing as a preventative strategy, the study’s findings call for strategic deployment grounded in crime type and neighborhood-specific data rather than blanket lighting upgrades.

The researchers emphasize that although their study did establish that darkness itself increases the risk for particular crimes, their current analysis does not incorporate the presence or absence of artificial lighting, such as street lamps, nor does it address the qualitative features of such lighting, including brightness or color spectrum. These aspects represent promising avenues for future investigations, which could provide actionable insights into optimizing artificial lighting as a tool for crime reduction.

The authors succinctly encapsulate the predicament faced by urban planners and police forces: "There is an assumption that street lighting helps reduce crime. Evidence in support of this assumption is unclear though. In our research, we took a step back and asked whether darkness itself increases crime risk. If it doesn’t, the presence or absence of street lighting is unlikely to matter." This critical perspective shifts the spotlight from the solutions towards re-examining the underlying problem.

Their partnership with South Yorkshire Police allowed access to rich data and applied statistical techniques to differentiate crime occurrences during daylight versus darkness, across a ten-year span. This extensive timeframe bolstered the reliability of their conclusions and reinforced the temporal trends observed within the dataset.

Importantly, the revelation that only certain crime types are linked to increased risk after dark could realign resource allocation strategies within policing frameworks. For instance, initiatives aimed at reducing burglary and vehicle offenses might benefit greatly from nighttime surveillance or tailored lighting, whereas other crimes may require alternative preventative measures.

Furthermore, the spatial variability reported by the study suggests that blanket policies may not serve all communities equally and that hyper-localized crime prevention mechanisms, possibly informed by neighborhood-specific lighting audits and crime mapping, should be developed.

While open questions remain, especially regarding the role and efficacy of artificial lighting technologies, Uttley and his colleagues’ work stands as a pivotal contribution to criminological science, demonstrating the value of integrating environmental factors such as darkness with large-scale, longitudinal crime data.

In sum, this detailed observational study not only confirms darkness as a significant variable in understanding crime risk but also paves the way for a more scientific, evidence-based approach to combatting crime after dark. This research could ultimately inform urban design, policing tactics, and community safety interventions, potentially leading to safer and more secure streets after sunset.

As societies continue to grapple with balancing safety concerns and the realities of urban darkness, studies like this provide essential empirical foundations upon which informed decisions and innovative crime prevention strategies can be built.

Subject of Research: People

Article Title: Does darkness increase the risk of certain types of crime? A registered report article

News Publication Date: 25-Jun-2025

Web References: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0324134

References: Uttley J, Canwell R, Smith J, Falconer S, Mao Y, Fotios S (2025) Does darkness increase the risk of certain types of crime? A registered report article. PLOS One 20(6): e0324134.

Image Credits: Uttley et al., 2025, PLOS One, CC-BY 4.0

Keywords: darkness, crime risk, street lighting, burglary, robbery, criminal damage, observational study, South Yorkshire, spatial analysis, crime prevention, urban safety, temporal crime patterns