In the intricate world of neuroscience, understanding the structural changes in the brains of individuals with schizophrenia has long posed a profound challenge. Schizophrenia, a complex psychiatric disorder, does not merely alter average brain volume in specific regions but is now increasingly recognized for its marked variability in brain structure across individuals. Traditionally, this variability has been perceived as a fixed characteristic, thought to signify the presence of heterogeneous subtypes within the broader diagnostic category. However, cutting-edge research spearheaded by Jiang, Palaniyappan, and colleagues disrupts this longstanding assumption, revealing that brain structure variability in schizophrenia is a dynamic phenomenon that evolves over the course of the illness.

This groundbreaking investigation utilized magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data from an unprecedentedly large cohort comprising 1,792 individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia alongside 1,523 healthy control subjects. By meticulously comparing gray matter volume variability between these groups, the study unveiled far more nuanced insights than previously appreciated. Remarkably, although greater variability was evident in patients with schizophrenia compared to controls across 50 brain regions, this heterogeneity was not static. Instead, it was heavily stage-dependent, displaying the highest degree of variability during the early, first-episode phase of schizophrenia and diminishing as the disorder transitioned into its chronic phase.

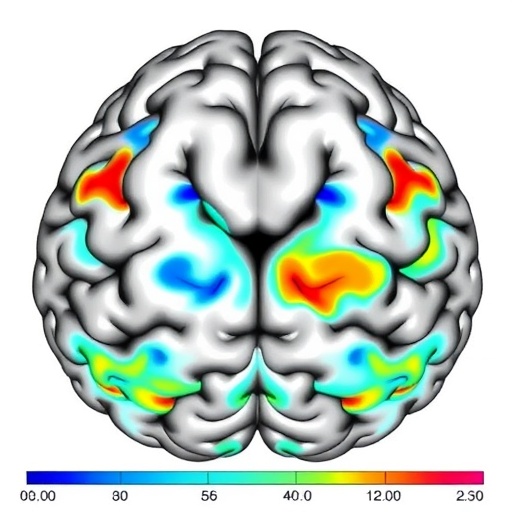

The implications of such findings flare across both clinical practice and theoretical frameworks. First-episode patients exhibited significantly more variable gray matter volumes—particularly within the frontotemporal cortex and the thalamus—highlighting regions widely implicated in the early pathophysiology of schizophrenia, including auditory processing and executive function disruptions. In contrast, chronic patients demonstrated reduced variability but with shifts in hotspot regions, most notably the hippocampus and the caudate nucleus. These latter brain structures are deeply intertwined with memory processes and motor functions, respectively, suggesting a potentially distinct trajectory of neuroanatomical changes as schizophrenia progresses.

The conventional model posited that the differences in brain structure reflect distinct subgroups with fixed traits, implying that patients with schizophrenia could be clustered into relatively homogenous categories based on their brain morphology. However, this extensive analysis challenges such a deterministic perspective, emphasizing instead a dynamic and evolving heterogeneity. This evolution might reflect a confluence of neurodegenerative processes, compensatory mechanisms, or the effects of prolonged treatment and environmental interactions over time. This dynamic approach opens a vital window into understanding why treatment responses, prognosis, and symptomatology vary widely across the schizophrenia spectrum.

Diving deeper into the methodological rigor of the study, the researchers applied stringent statistical corrections, including false-discovery-rate adjustments, to definitively identify regions of significant variability difference. The frontotemporal cortex and thalamus’s early prominence in variable morphology aligns with the regions’ critical roles in cognitive and sensory integration, which are often dysregulated at illness onset. These findings extend previous volumetric analyses, which primarily focused on mean volume differences, underscoring the added value of examining variance and distribution of brain structural data to capture the biological complexity of schizophrenia.

Of particular interest is the observation that the decrease in variability between the first-episode and chronic stages was not just a subtle trend but exhibited robust statistical significance. The t-score of 10.8 and p-value on the order of 10^-7 highlight a profound and reproducible effect, strengthening the argument for stage-dependent plasticity or neurobiological stabilization in advanced stages of the disorder. Such trajectories could reflect either a convergence toward an “end-stage” morphology among chronic patients or perhaps a pruning of neuroanatomical anomalies over time.

The study also sheds light on the importance of the hippocampus and caudate during the chronic phase. The hippocampus, widely known for its involvement in memory and spatial navigation, is frequently implicated in schizophrenia’s cognitive deficits, while the caudate nucleus, part of the basal ganglia, is crucial for motor function and procedural learning. Variability in these regions could suggest ongoing neurodegenerative processes or synaptic remodeling influenced by disease progression, medication effects, or lifestyle factors such as social isolation or stress.

This nuanced understanding of brain heterogeneity carries significant implications for precision medicine. If variability patterns change dynamically over time, therapeutic interventions should be tailored not only to symptom profiles but also to the patient’s stage of illness and possibly even to the shifting neuroanatomical landscape. Early intervention strategies might target stabilization or normalization in highly variable regions like the frontotemporal cortex and thalamus, whereas care in chronic stages might benefit from focusing on supporting hippocampal integrity and basal ganglia functions.

Equally compelling are the theoretical ramifications. The observed stage-dependent variability challenges reductionist conceptions of schizophrenia as a constellation of fixed subtypes. Instead, it suggests schizophrenia is best conceptualized as a fluid neurobiological continuum characterized by evolving patterns of brain alteration. This dynamic heterogeneity could reflect developmental disruptions, adaptive neuroplastic responses, or cumulative effects of illness and treatment. Thus, variability itself may be a biomarker of the underlying pathophysiology’s trajectory rather than a static trait marker.

From a technological standpoint, the use of magnetic resonance imaging across multiple sites and a vast sample enhances the generalizability of the findings. Such large-scale neuroimaging consortia are instrumental in overcoming the limitations of sample size and heterogeneity that have historically hindered robust conclusions in psychiatric neuroimaging research. Furthermore, this study exemplifies how advanced statistical modeling and rigorous quality control can transform complex datasets into actionable neurobiological insights.

Looking forward, this research paves the way for multi-modal investigations that integrate structural variability measures with functional imaging, genetic profiles, and clinical trajectories. Understanding how gray matter volume variability correlates with symptom clusters, cognitive function, and treatment outcomes could unlock new predictive algorithms and therapeutic windows. Moreover, longitudinal studies can unravel whether pharmacological or behavioral interventions modulate this variability across disease stages, illuminating pathways for neuroprotection or rehabilitation.

The revelation that brain heterogeneity is more pronounced at illness onset but attenuates over time also invites a reconsideration of the mechanisms underpinning disease progression. Neuroinflammation, synaptic pruning abnormalities, oxidative stress, and glial dysfunction—all previously implicated in schizophrenia—may variably influence brain structure as schizophrenia evolves. Disentangling these processes will require multidisciplinary research, marrying neuroimaging with molecular and cellular neuroscience to chart the landscape of brain remodeling in this enigmatic disorder.

In sum, Jiang and colleagues’ landmark study decisively shifts the narrative surrounding brain structural variability in schizophrenia. It spotlights heterogeneity not as a static hallmark but as a dynamic feature influenced by disease stage, brain region, and possibly multiple biological pathways. This paradigm shift invites a reevaluation of diagnostic categories, personalized treatment frameworks, and research strategies aimed at decoding schizophrenia’s complex neurobiology.

As schizophrenia continues to affect millions worldwide, innovations that deepen our understanding of its neuroanatomical underpinnings are urgently needed. By illuminating the evolving nature of brain variability, this research offers hope that more precise, timely, and effective interventions can be developed—transforming lives and reshaping the future of mental health care.

Subject of Research: Neuroanatomical variability and its stage-dependent changes in schizophrenia, exploring gray matter volume heterogeneity through large-scale MRI analysis.

Article Title: Gray matter volume heterogeneity by stage, site of origin and pathophysiology in schizophrenia.

Article References:

Jiang, Y., Palaniyappan, L., Chang, X. et al. Gray matter volume heterogeneity by stage, site of origin and pathophysiology in schizophrenia. Nat. Mental Health (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00449-9

Image Credits: AI Generated