In a groundbreaking study published in the journal “Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences,” researchers Martín A.G., Portillo M., and López J.M.C. explore the intricate relationship between household economies and food technologies during the Late Iron Age in the Eastern Pyrenees. Their investigation dives deep into the grinding practices evidenced at El Castellot de Bolvir, an archaeological site located in La Cerdanya, Spain. This research integrates archaeological findings with socio-economic analyses to shed light on the culinary techniques and subsistence strategies that defined this ancient civilization.

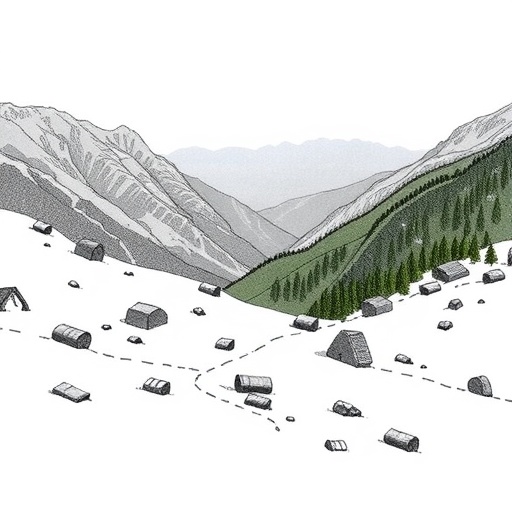

The Eastern Pyrenees are often overlooked in discussions of ancient Mediterranean societies, yet the findings presented by the research team illustrate the area’s significant role in the larger tapestry of European prehistory. The grinding activities that took place at El Castellot de Bolvir reveal a great deal about everyday life, including diet, agricultural practices, and technological advancements. By examining the grinding stones and materials left behind at the site, the researchers are piecing together a picture of how communities utilized local resources to meet their needs.

The study capitalizes on a range of archaeological methodologies, including the analysis of grindstone wear patterns, residue analysis, and spatial organization of artifacts within the site. Such methodologies allow researchers to not only identify what types of grains or seeds were processed but also to understand the scale and intensity of food production. This is crucial for developing a comprehensive understanding of the socio-economic framework of these Iron Age communities.

Furthermore, the analysis extends to ancient food technologies and how they influenced local economies. By tracking the production processes associated with grinding, the authors argue that this activity was not merely utilitarian; it was also deeply embedded in cultural practices and social structures. The transition from wild to domesticated grains, for example, marks a significant shift in the practices that shaped dietary habits. This shifts in food preparation techniques reflect broader changes in lifestyle and economy during this period.

In examining the grinding techniques themselves, the study sheds light on variations in tool use and technological innovation. The researchers classify the grinding implements based on size, shape, and wear characteristics, providing insights into how different tools might have been adapted for specific tasks. The presence of various grain types, such as barley and wheat, indicates a diverse diet and a sophisticated understanding of agricultural possibilities in this mountainous region.

The contextualization of grinding activities within the domestic sphere offers compelling insights into household economies. The study suggests that food production and consumption were closely tied to familial and communal activities, which reinforced social bonds and cultural identity. Meals prepared from ground grains were likely central to ceremonial practices and daily sustenance, illustrating how food was more than just fuel; it was integral to community cohesion.

Moreover, the socio-political environment of the Late Iron Age is considered in conjunction with these technological practices. The study posits that the grinding activities may have played a role in social stratification, as control over food production methods could confer power and status within these early societies. The ability to produce and manage food resources was critical, and those who excelled in these practices might have been pivotal figures in local governance.

Notably, the authors emphasize the significance of inter-regional trade in understanding the grinding practices at El Castellot de Bolvir. Evidence of exchange with neighboring communities suggests that the output from these grinding activities was not solely for local consumption but may have been part of a larger trade network. This exploration of economic interactions paints a picture of a dynamic societal landscape where goods, ideas, and technologies were shared and adapted across regional boundaries.

The implications of these findings extend beyond the specifics of the Pyrenees and resonate with broader anthropological discussions about the evolution of food production technologies across ancient civilizations. By contributing to the growing body of knowledge regarding prehistoric economies, the research offers a template for exploring similar sites around the world, prompting questions about how technology influences societal development.

The authors also delve into the environmental context of food production, specifically focusing on the adaptation strategies employed by communities in this high-altitude region. The interplay of climate, terrain, and soil fertility posed unique challenges that required innovative solutions. The advanced grinding techniques developed at El Castellot de Bolvir demonstrate resilience and adaptability, key traits of successful prehistoric societies.

This research not only enriches our understanding of the Eastern Pyrenees during the Late Iron Age but also opens avenues for future studies. The methodologies employed by the researchers can be applied to other archaeological sites, making this work a valuable reference for scholars interested in food technologies and household economies in different cultural contexts.

In essence, the study of El Castellot de Bolvir reveals the complexities of daily life in the Late Iron Age and underscores the significance of food technologies in shaping human society. It compellingly argues that the seemingly mundane act of grinding grain is embedded with rich narratives about identity, economy, and culture, reminding us that food is a profound marker of human experience across time.

As archaeologists continue to unearth remnants of ancient civilizations, such studies serve as a reminder of the importance of examining the technologies that have long sustained human life. The role of grains, grinding techniques, and domestic economies will undoubtedly feature prominently in future archaeological inquiries, inviting us to reimagine our understanding of the past.

With this profound research into the past, Martínez, Portillo, and López offer a timely reminder of the enduring significance of food in our modern lives, linking ancient practices to contemporary understandings of nutrition, sustainability, and communal living.

Through their detailed examination of grinding practices in the Eastern Pyrenees, the researchers have opened a window into a time gone by, illuminating not only the technological expertise of a bygone era but also the very human concerns that continue to shape our societies today.

Ultimately, this study emphasizes that the act of food preparation is not just a mundane chore but a profound aspect of human existence, connecting us to our ancestors and showcasing the enduring legacy of our agricultural practices.

Subject of Research: Household economies and food technologies in the Eastern Pyrenees during the Late Iron Age.

Article Title: Tracing household economies and food technologies in the Eastern Pyrenees: grinding at Late Iron Age of El Castellot de Bolvir (La Cerdanya, Spain).

Article References:

Martínez, A.G., Portillo, M., López, J.M.C. et al. Tracing household economies and food technologies in the Eastern Pyrenees: grinding at Late Iron Age of El Castellot de Bolvir (La Cerdanya, Spain).

Archaeol Anthropol Sci 18, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-025-02352-x

Image Credits: AI Generated

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-025-02352-x

Keywords: Grinding practices, Late Iron Age, Eastern Pyrenees, food technologies, household economies, archaeological methodologies, El Castellot de Bolvir.