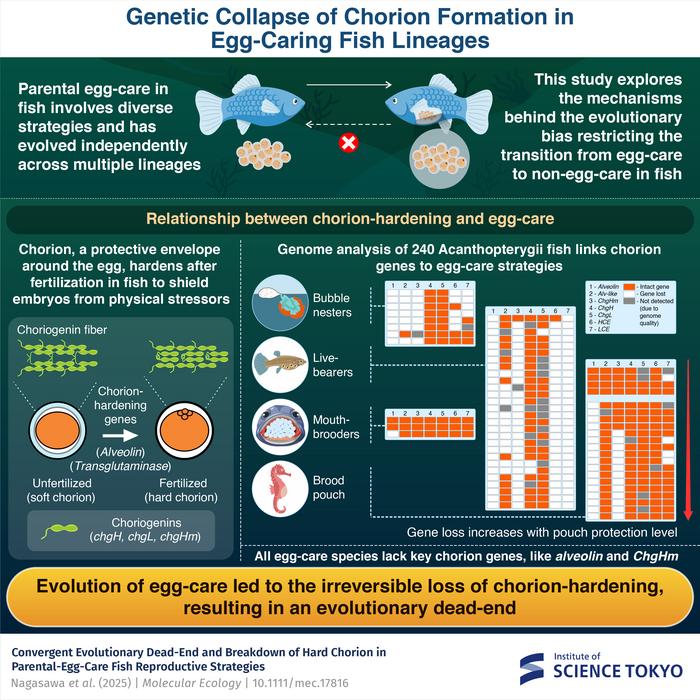

In an unprecedented genomic study, scientists from the newly established Institute of Science Tokyo have uncovered the genetic underpinnings that lead to what they describe as an “evolutionary dead-end” for fish species that engage in parental egg-care. By analyzing whole genome sequences from 240 distinct species within the diverse Acanthopterygii superorder, the research reveals a striking and irreversible collapse of the chorion-hardening system—a critical protective barrier in fish eggs—among egg-caring lineages. This discovery provides profound insights into the evolutionary constraints and trade-offs linked to reproductive strategies in vertebrates.

Fish, as the most speciose group of vertebrates, exhibit a vast array of reproductive modes, ranging from externally fertilized eggs with no parental involvement to complex forms of brood care such as mouthbrooding and pouch brooding. These divergent strategies have evolved multiple times independently, reflecting ecological adaptations to varying environmental pressures. However, one enigmatic aspect in evolutionary biology has been the asymmetry in transitions: shifts from non-egg-care to egg-care behaviors are relatively common, but reversions to non-egg-care remain scarce. The genomic factors underlying this one-way evolutionary trajectory have largely remained elusive until now.

Central to this study is the chorion, the extracellular matrix that envelops fish eggs. Post-fertilization, the chorion undergoes a hardening process, which establishes a durable protective shell resisting physical and microbial threats. Traditionally, species that do not invest in parental care rely heavily on this hardened chorion to safeguard their offspring in often precarious environmental conditions. Conversely, species exhibiting parental care tend to have thinner, more fragile chorions, presumably because parental behaviors compensate for the chorion’s reduced protective qualities.

Assistant Professor Tatsuki Nagasawa and collaborators harnessed the power of comparative genomics combined with evolutionary analyses to pinpoint the molecular components responsible for this differential chorion hardening. Their focus was on a well-characterized set of genes encoding proteins that catalyze and regulate the chorion’s transformation post-fertilization. Among these, the gene alveolin, known to be pivotal in mediating chorion hardening through enzymatic cross-linking of chorion proteins, emerged as a critical factor demonstrating consistent loss or pseudogenization across all egg-caring species examined.

The research team mapped evolutionary changes in the alveolin gene and related gene clusters across 25 orders of Acanthopterygii fish. Their results strikingly show repeated, independent losses of alveolin corresponding precisely with multiple independent transitions toward parental egg-care. Remarkably, in the order Syngnathiformes—famous for male brood pouches where males incubate fertilized eggs—the extent of alveolin gene degradation correlates with the level of physical protection provided by the male’s brood pouch. Species with fully enclosed, sac-like pouches exhibited complete loss-of-function mutations within alveolin, indicating a perfect example of gene decay aligned with physiological innovations in reproductive behavior.

This gene-loss event is more than a mere molecular curiosity; it constitutes an evolutionary bottleneck with significant biological and ecological implications. The irreversibility of alveolin degradation implies that once a lineage commits to parental egg-care, reversion back to non-care strategies is genetically impeded, effectively locking these fish into a narrow reproductive niche. Such an evolutionary dead-end may severely limit adaptive potential in the face of environmental change, where parental care behaviors could become maladaptive if conditions shift drastically.

The researchers highlight the conservation ramifications of these findings, noting that environmental disturbances impairing parental care could disproportionately impact egg-care species due to their reliance on fragile chorions and parental protection. Future conservation strategies may benefit from genomic biomarkers, such as alveolin gene status, to assess reproductive resilience and vulnerability in endangered fish populations without invasive sampling.

Moreover, this study advances our understanding of how gene loss can drive evolutionary novelty while simultaneously imposing constraints. It exemplifies a genomic trade-off where traits facilitating reproductive success in one context may diminish flexibility in another. The interplay between gene retention, loss, and behavioral evolution illustrates the complexity of selective pressures sculpting vertebrate reproductive strategies over millions of years.

Beyond expanding evolutionary theory, these findings present a novel framework for interpreting reproductive diversification in other taxa. The convergence of gene decay with behavioral adaptations underscores that phenotypic plasticity may be underpinned by irreversible genetic changes, challenging assumptions about the reversibility of complex traits.

By integrating detailed genomic datasets with ecological and reproductive phenotypes, Assistant Professor Nagasawa’s team has forged a path toward deciphering the molecular echoes of past evolutionary decisions. Their work, soon to be published in the esteemed journal Molecular Ecology, not only deepens our understanding of fish biology but also enriches evolutionary biology’s discourse on the limits of adaptation and the landscape of reproductive innovation.

The implications of these results also extend to evolutionary developmental biology, as understanding how gene networks degrade or adapt in correlation with behavioral changes can highlight the genetic mechanisms shaping life history traits. This knowledge has the potential to inform breeding programs and aquaculture practices by illuminating constraints on reproductive plasticity.

As fish continue to face changing aquatic environments, from pollution to climate-driven habitat alterations, insights into their reproductive vulnerabilities and strengths become all the more critical. The genomic evidence of a hard biological boundary imposed by the loss of chorion-hardening genes offers a cautionary tale about the possible rigidity of evolutionary pathways.

In summary, the comprehensive comparative genomic approach taken by the Institute of Science Tokyo illustrates how gene loss associated with reproductive innovations can result in evolutionary dead-ends, shaping the destiny of species for millions of years. The study eloquently captures the intricate dance between genetics and behavior, revealing the irreversible nature of some evolutionary transitions and providing a molecular window into the enduring consequences of parental care strategies in fish.

Subject of Research: Animals

Article Title: Convergent evolutionary dead-end and breakdown of hard chorion in parental-egg-care fish reproductive strategies

News Publication Date: 2-Jun-2025

Web References: https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17816

Image Credits: Institute of Science Tokyo

Keywords: Evolutionary ecology, Ecology, Environmental sciences, Ecological adaptation, Ecological speciation, Fresh water fishes, Marine fishes, Vertebrates, Fish, Evolutionary biology, Organismal biology, Animals