In the rapidly changing climate of our planet, one particularly alarming phenomenon is the thawing of permafrost—previously frozen ground that has remained intact for millennia in polar and subpolar regions. A groundbreaking study recently published in Nature Communications has unveiled startling insights into how earlier permafrost thawing is dramatically accelerating land surface greening, reshaping ecosystems and biogeochemical cycles in profound and unexpected ways. This research not only deepens our understanding of Arctic and subarctic environments under stress but also highlights far-reaching implications for global climate feedbacks and carbon cycle dynamics.

Permafrost acts as a vast natural repository of organic carbon, holding roughly double the carbon currently present in the atmosphere. Traditionally, this organic material has remained locked beneath the frozen earth, inert and inaccessible to biological decomposition. However, with sustained global warming trends, permafrost layers are undergoing progressive warming and thawing earlier in the calendar year, significantly extending the period during which formerly frozen soil becomes biologically active. This extended thaw window facilitates enhanced microbial activity and nutrient cycling, setting the stage for a pronounced transformation of the land surface.

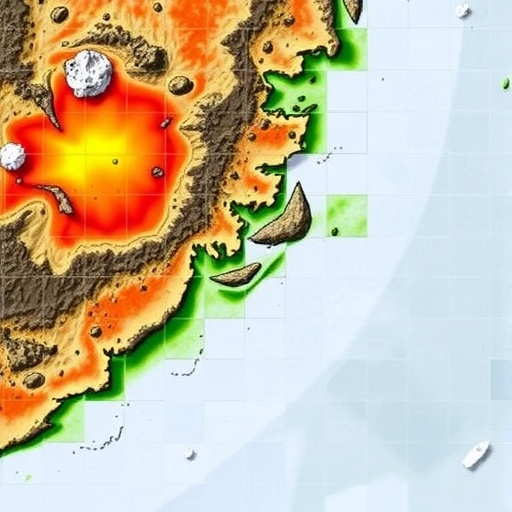

One of the most striking consequences of earlier permafrost thawing is an accelerated expansion of vegetation cover, or “greening,” across previously sparse tundra landscapes. The study harnesses a combination of satellite remote sensing and ecosystem modeling to quantify changes in land surface vegetation indices over the past two decades. These data reveal a clear temporal correlation between earlier seasonal thaw onset and a marked increase in photosynthetic activity, suggesting that thaw advances are effectively lengthening the Arctic growing season. This phenomenon, while seemingly beneficial in terms of enhanced primary productivity, carries nuanced ecological ramifications.

Research indicates that the greening trend is not uniform across all permafrost zones. Areas with ice-rich, highly organic soil profiles exhibit the most pronounced vegetation responses, driven in part by increased soil moisture and nutrient availability following thaw. Plants respond rapidly to these improved soil conditions with increased leaf area and biomass production, particularly favoring deciduous shrubs and graminoids. This compositional shift may accelerate nutrient turnover and alter habitat structure, influencing wildlife populations and overall biodiversity.

Moreover, the earlier thaw and resulting vegetation growth catalyze complex feedback loops involving surface energy balance. Enhanced plant canopy cover modifies albedo—the reflectance of solar radiation—leading to a reduction in the amount of sunlight reflected back into the atmosphere. This darker land surface absorbs more heat, further increasing soil temperatures and potentially accelerating permafrost degradation in a positive feedback cycle. This mechanistic insight elucidates how biophysical changes interplay with biogeochemical processes in a warming Arctic.

Crucially, the study also delves into the carbon cycle implications arising from accelerated greening. While increased vegetation growth theoretically enhances atmospheric carbon uptake through photosynthesis, it simultaneously triggers elevated microbial decomposition of thawed organic matter, releasing substantial amounts of carbon dioxide and methane—potent greenhouse gases. The net effect on carbon balance depends heavily on the relative rates of these opposing processes and varies spatially and temporally. Their sophisticated ecosystem model simulations suggest that initial carbon uptake benefits from greening may be offset by accelerated soil respiration over longer timescales.

Beyond carbon dynamics, earlier permafrost thaw influences hydrological patterns, which, in turn, affects vegetation dynamics. Thaw-induced changes in soil permeability and water retention alter drainage patterns, potentially leading to wetter soils that promote the establishment of certain plant species over others. These hydrological shifts can complicate predictions about future ecosystem trajectories, as moisture availability is a critical determinant of species composition and productivity in cold environments.

The observational data sets employed in the study span multiple decades, integrating satellite-derived Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) metrics, soil temperature records, and various climatic parameters. Such long-term, multi-modal data amalgamation strengthens the conclusion that the observed greening is primarily a response to earlier permafrost thaw and not merely transient weather variability. This robustness enhances confidence in projecting future trends as climate warming persists and intensifies.

The finding that permafrost thaw is advancing earlier annually aligns with broader climate model projections but adds an important temporal dimension to land surface response assessments. Earlier thaw onset is estimated to extend the growing season by as much as several weeks in some regions, a substantial period in ecosystems traditionally characterized by brief summers. This extended timeframe facilitates not only increased carbon uptake but also enhances reproductive cycles and phenological events in local flora and fauna.

Another compelling aspect highlighted by the research is the potential for synergistic effects between warming and other environmental factors like increased nutrient deposition from atmospheric sources and changing snow cover patterns. Declines in snow insulation during winter might paradoxically lead to more severe soil freeze-thaw cycles, complicating permafrost dynamics. These interacting variables underscore the complexity inherent in modeling ecosystem responses in high-latitude environments.

Considering global implications, the accelerated greening and associated biochemical feedbacks from earlier permafrost thaw represent a double-edged sword in climate mitigation. While enhanced vegetation cover could theoretically sequester more carbon, the concomitant increase in greenhouse gas emissions from decomposing permafrost material may contribute to warming amplification. This paradox illustrates the critical need to accurately account for permafrost processes in Earth system models to refine predictions of future climate trajectories.

Phenological shifts linked to earlier thaw also have cascading effects on Arctic food webs and indigenous communities relying on these ecosystems for subsistence. Changes in plant species composition and productivity impact herbivore food sources and migration patterns, which ripple through trophic layers. Understanding these ecological intricacies is essential not just for climate science but for supporting adaptive management strategies that accommodate rapidly changing northern environments.

The study also paves the way for emerging research to investigate potential mitigation approaches. For instance, increasing understanding of permafrost-vegetation feedbacks may inform land management practices designed to preserve or restore carbon sinks. Experimental manipulations of thaw rates and vegetation could shed light on pathways to curtail deleterious emissions while sustaining ecosystem functions crucial to temperature regulation and biodiversity.

In conclusion, the revelation that permafrost thawing is occurring earlier than previously anticipated, catalyzing accelerated land surface greening, marks a pivotal advance in climate change science. It signals a dynamic transformation unfolding at high latitudes with critical ramifications for global biogeochemical cycles and climate feedbacks. This deeper mechanistic understanding enriches the dialogue on how natural systems respond to warming trends and underscores the urgency of integrating permafrost dynamics into broader climate models and policy frameworks.

Future research will be instrumental in unraveling remaining uncertainties surrounding the balance of carbon fluxes, ecosystem resilience, and hydrological modifications induced by earlier permafrost thaw. Interdisciplinary collaboration bridging remote sensing, field observations, and process-based modeling will continue to illuminate pathways for mitigating climate risks while appreciating the profound environmental shifts already underway in the frozen frontiers of our planet.

This compelling study not only advances scientific knowledge but also galvanizes global attention toward the vulnerabilities and complexities inherent in Earth’s cryosphere. As the world continues to grapple with escalating climate change impacts, such insights will remain foundational to informed decision-making, responsible stewardship, and adaptive resilience in the face of an uncertain future.

Subject of Research: Impacts of earlier permafrost thaw on Arctic land surface greening and associated ecological and biochemical processes.

Article Title: Accelerated land surface greening caused by earlier permafrost thawing.

Article References:

Hua, H., Wang, J., Zohner, C.M. et al. Accelerated land surface greening caused by earlier permafrost thawing. Nat Commun (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67644-1

Image Credits: AI Generated