In a groundbreaking study published in Nature Communications, a consortium of climate scientists and oceanographers led by Lu, L., Yang, Q., and Gutjahr, M. unveils a fascinating decoupling of export productivity patterns between Antarctic and Subarctic regions during the last interglacial period. This research offers a nuanced understanding of how intensified Southern Hemisphere westerly winds—key drivers of ocean circulation—shaped global carbon cycling and marine ecosystems some 127,000 years ago, during the Eemian interglacial. Their findings illuminate complex ocean-atmosphere interactions under past climate conditions that bear critical implications for projecting future climate trajectories amid ongoing anthropogenic change.

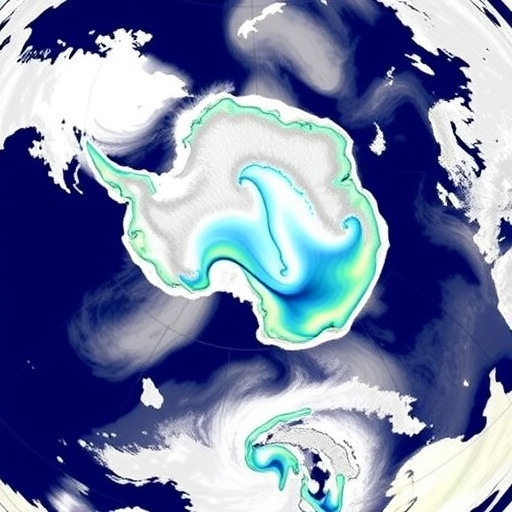

The last interglacial, a natural warm period that preceded our current Holocene epoch, provides an invaluable analog for Earth’s climate system under warming scenarios. This interval saw temperatures rivaling or exceeding those of today, accompanied by altered atmospheric circulation patterns. Central to this new investigation is the intensified activity of the Southern Hemisphere westerly winds, powerful belts of prevailing winds coursing from west to east between 30° and 60° latitude in the Southern Ocean region. These winds influence ocean upwelling, nutrient supply, and carbon sequestration on a vast scale.

Conventional understanding has long presumed synchronous changes in ocean productivity across Southern Ocean sectors responding uniformly to shifts in westerly wind strength. However, the novel multiproxy data synthesis from sediment cores spanning Antarctic and Subarctic domains challenges this assumption. Lu and colleagues reveal a surprising divergence in how export productivity—the flux of organic carbon from the ocean surface to depth—responded to climatic forcing, indicating a spatially heterogeneous ocean response to atmospheric changes during the last interglacial.

The study leverages a combination of state-of-the-art geochemical proxies extracted from marine sediments, including rare earth element compositions, organic carbon isotopes, and foraminiferal assemblages. These proxies meticulously reconstruct past variations in biological productivity, ocean circulation patterns, and nutrient dynamics. The precision and spatial coverage of the dataset surpass previous research efforts, providing an unprecedented window into regional biogeochemical feedbacks over millennial timescales.

One of the key revelations unearthed by this research is that Antarctic export productivity increased significantly under intensifying westerly winds, driven by enhanced upwelling of nutrient-rich deep waters. This process fueled phytoplankton growth, which in turn amplified the biological carbon pump, transferring carbon dioxide from surface waters to the deep ocean and affecting atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations. Simultaneously, a contrasting decline in Subarctic export productivity was observed, implying a decoupling of the Southern Ocean’s two pivotal ecological zones.

This divergent response is hypothesized to result from shifts in oceanic fronts and stratification patterns, fundamentally altering nutrient availability and ecosystem dynamics on either side of the Antarctic Polar Front. The Antarctic sector benefitted from enhanced nutrient entrainment linked to increased westerly wind stress, while the Subarctic region experienced stratification changes limiting primary productivity despite the same climatic drivers. This intricate interplay underscores the heterogeneity and sensitivity of ocean biogeochemistry to atmospheric forcing.

Moreover, the research team integrated Earth system models calibrated with paleoclimate proxy data to elucidate the mechanistic underpinnings of observed productivity patterns. Simulations confirm that intensified westerly winds drive stronger upwelling and carbon export in circumpolar Antarctic waters but produce stratification-induced productivity reductions in adjacent Subarctic zones. These models highlight the critical influence of latitudinal ocean dynamics in modulating carbon cycling within the Southern Hemisphere, with implications for atmospheric CO₂ variability during warm climate intervals.

Understanding this spatial decoupling during the last interglacial has profound ramifications for interpreting how modern and future shifts in Southern Hemisphere westerlies might influence ocean productivity and carbon sequestration. Recent observational evidence points to a poleward shift and intensification of these winds under anthropogenic climate forcing, raising concerns about the ensuing impacts on ocean ecosystems and feedbacks to the global carbon budget.

This study also carries significant weight for refining paleoclimate reconstructions. Previous climate models inadequately incorporated heterogeneous ocean responses to wind forcing, often treating Southern Ocean productivity as spatially homogeneous. The novel findings advocate for incorporating region-specific biological and physical oceanographic processes to better predict carbon cycle dynamics under interglacial and future warm climate conditions.

The implications extend beyond academia into climate policy and mitigation strategies. Since export productivity plays a key role in sequestering CO₂ from the atmosphere, understanding its variable response to wind patterns can enhance the accuracy of carbon budget assessments. This is crucial for forecasting oceanic carbon sinks’ resilience or vulnerability amid accelerating climate change and for informing geoengineering debates surrounding ocean fertilization and carbon sequestration methods.

The researchers emphasize that while the last interglacial provides a valuable analog, contemporary anthropogenic influences—such as ocean acidification, warming, and nutrient perturbations—introduce additional complexities. Therefore, ongoing research integrating sediment proxy analysis with modern observational datasets and advanced climate modeling remains vital to comprehensively map future ocean productivity responses.

In conclusion, the work by Lu, Yang, Gutjahr, and colleagues brings to light a previously underappreciated spatial heterogeneity in Southern Hemisphere marine productivity responses under intensified westerly winds during a warm and climatically significant era. By combining innovative sedimentary proxy methodologies with robust climate modeling, they chart new territory in understanding ocean-atmosphere coupling and carbon cycling dynamics intrinsic to Earth’s climate system. This research not only revises prevailing paradigms about past ocean productivity but also sets a new benchmark for future studies probing the climatic consequences of changing wind patterns in a warming world.

Their findings resonate strongly in the context of accelerating global climate change, offering a prescient glimpse at the complex feedbacks that regulate ocean ecosystems and the global carbon cycle. As humanity grapples with the challenges posed by climate disruption, deciphering such past episodes of rapid environmental transformation provides crucial knowledge for anticipating and mitigating the impacts on ocean biogeochemical systems critical to sustaining planetary habitability.

Subject of Research:

Deciphering the decoupling of Antarctic and Subarctic ocean export productivity during the last interglacial period and its relationship with intensified Southern Hemisphere westerly winds.

Article Title:

Decoupled Antarctic and Subarctic export productivity under intensified Southern Hemisphere westerlies during the last interglacial.

Article References:

Lu, L., Yang, Q., Gutjahr, M. et al. Decoupled Antarctic and Subarctic export productivity under intensified Southern Hemisphere westerlies during the last interglacial. Nat Commun (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66289-4

Image Credits:

AI Generated