Satellite imagery has unveiled a fascinating network of ancient hunting traps embedded in the high-altitude landscapes of northern Chile’s Andean highlands. These elaborate stone structures, described as funnel-shaped mega traps, represent a sophisticated strategy employed by prehistoric hunters and pastoralists to capture vicuñas—a wild relative of modern alpacas. The discovery of these structures, known locally as “chacus,” adds a significant chapter to our understanding of human-animal interactions and survival techniques in one of the world’s most challenging environments.

The study, led by Dr. Adrián Oyaneder from the University of Exeter’s Department of Archaeology and History, systematically examined a vast 4,600 square-kilometer area within the Camarones River Basin using publicly accessible satellite data. This remote, rugged terrain had remained relatively unexplored archaeologically until now. Dr. Oyaneder identified an impressive 76 chacus, massive in scale and dimension, with many stretching hundreds of meters long. These were carefully constructed using dry-stone walls averaging 1.5 meters in height, tapering into a confined enclosure roughly 95 square meters in size, designed to trap animals, presumably vicuñas, once funneled in.

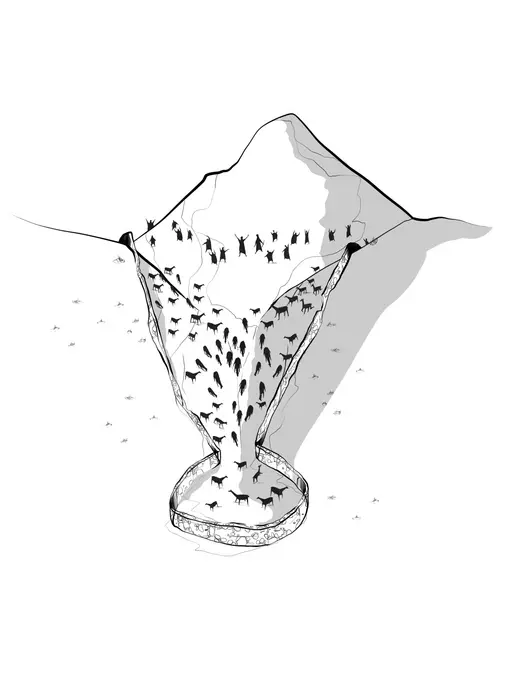

The architectural design of these chacus presents a highly effective trap mechanism. Each structure consists predominantly of two linear stone “antennae” that converge on steep downhill slopes, utilizing natural topography to enhance their function. The enclosures at the narrow funnel ends are either dug or naturally recessed to a depth of approximately two meters, sufficient to contain the animals once trapped. The location and orientation of these structures correspond strikingly with vicuña habitats, hinting at a deep ecological knowledge and adaptation by these ancient peoples to their environment.

This discovery challenges conventional narratives about the gradual decline of hunter-gatherer lifestyles in the Andean region following the adoption of agriculture and animal domestication from around 2000 B.C. On the contrary, data suggests a well-preserved hunting culture that persisted alongside agropastoral practices deep into the colonial period. Spanish colonial tax records, referring to groups generically as ‘Uru’ or ‘Uro,’ previously dismissed these foragers as insignificant economic actors. However, the archaeological evidence unearthed by Dr. Oyaneder paints a picture of vibrant communities maintaining dynamic and complex lifestyles tethered to seasonal hunting and mobility.

Beyond the chacus, almost 800 small-scale settlements and outposts were documented. These ranged from scant single-roomed buildings of barely one square meter footprint to clustered groups of nine or more structures. Spatial analysis using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) revealed that these human habitations were strategically clustered within five kilometers of the trap sites, reflecting a landscape of interconnected hunting groups that moved systematically across these harsh highlands in pursuit of vicuñas and other resources.

The temporal depth of human activity in the Western Valleys is profound, with indications that these specialized hunting populations occupied the region from as early as 6000 B.C. through to the eighteenth century. This long-term habitation reflects a resilient adaptability, blending traditional foraging with emerging agricultural and pastoral economies. Such coexisting lifeways underscore the fluidity of human subsistence strategies in the past, far from the rigid categories often assumed in archaeological narratives.

Dr. Oyaneder’s research integrates ethnohistorical accounts, archaeological data, and cutting-edge remote sensing technology to redefine our understanding of ancient Andean societies. Particularly enlightening are the historic ethnographic references found in the works of anthropologists such as Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne and Olivia Harris, which describe specialized vicuña hunters—choquela—and use terminology explicitly linked to the chacu hunting technique. This linguistic and cultural continuity lends robust context to the satellite findings, suggesting a deeply rooted tradition of large-scale communal hunting.

The technological methodology behind the rediscovery cannot be overstated. Satellite imaging analysis, coupled with extensive ground verification, enabled the detection of these expansive, previously unnoticed stone constructions scattered across the valleys. The vivid contrast these stone walls present against the barren highland terrain makes them excellent candidates for remote sensing techniques, revolutionizing the potential for large-scale archaeological surveys in similarly difficult and inaccessible environments globally.

These monumental traps demonstrate not only the ingenuity of ancient Andean hunters but also hint at complex social organization. Coordinated communal hunts using mega traps imply communication, planning, and labor investment. Such sophistication challenges prior assumptions about the social complexity of pre-Incan and colonial-era societies in the region, indicating that these groups employed advanced methods to sustainably harvest wild vicuñas over millennia.

Currently, Dr. Oyaneder is extending his investigations to determine the precise chronological framework of these sites. By dating layers of use and settlement remains, the research hopes to establish whether these chacus could predate those utilized by the Inca Empire, potentially redefining the timeline of large-scale hunting technologies in South America. Confirmation of their pre-Incan origins would situate this network as some of the earliest mega trap systems globally, inviting comparisons with analogous structures documented in the Middle East and other arid regions.

The implications of this research extend beyond archaeological curiosity, offering vital insights into human resilience and adaptation in extreme ecologies. Understanding the intricate relationship between ancient peoples and vicuñas contributes valuable knowledge toward biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management in the present-day Andes, where climate change and human pressures continue to threaten both animal populations and indigenous cultural heritage.

Published in the highly respected journal Antiquity and funded by Becas Chile-ANID doctoral scholarships along with the FONDECYT project led by Dr. Daniela Valenzuela of Universidad de Tarapacá, this study exemplifies the synergy between modern scientific innovation and classical archaeological investigation. It opens new horizons for exploring how ancient communities constructed their lifeways through ingenuity, collaboration, and deep environmental knowledge, echoing lessons that remain relevant today.

As remote sensing and GIS technologies continue to advance, the potential to uncover hidden archaeological landscapes in extreme environments will likewise grow, promising further revelations about humanity’s ancient ingenuity. The chacus of northern Chile stand as monumental testaments to a tethered lifestyle of mobility and hunting—a lasting imprint of a people intimately connected to the Andean highlands they called home.

Subject of Research: People

Article Title: A tethered hunting and mobility landscape in the Andean highlands of the Western Valleys, northern Chile

News Publication Date: 13-Oct-2025

Web References: http://dx.doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10213

Image Credits: Gerald Díaz-Vigil

Keywords: Andean archaeology, satellite imagery, chacu, vicuña hunting, hunter-gatherer, pastoralism, ancient mega traps, mobility landscape, Northern Chile, GIS archaeology, pre-Incan societies, high-altitude hunting