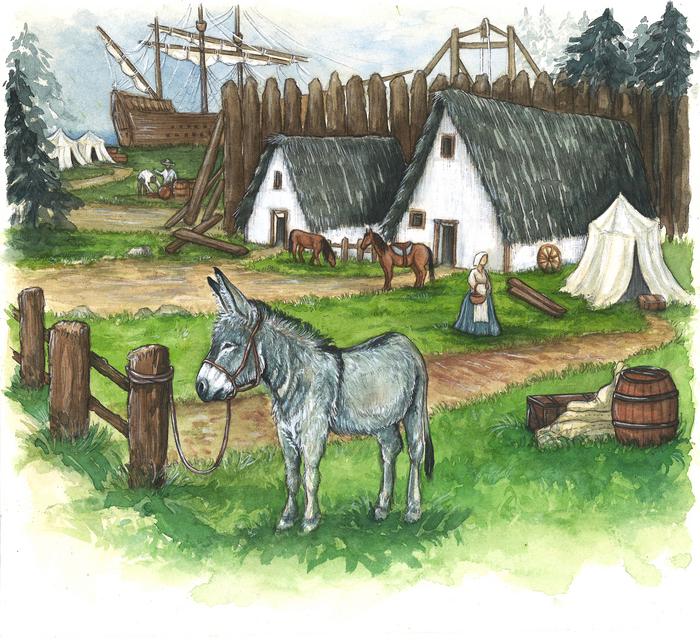

In a groundbreaking archaeological revelation, a recent study published in Science Advances has radically transformed our understanding of the early transatlantic introduction of horses and donkeys into North America, specifically through the Jamestown settlement in Virginia. This research, leveraging advanced zooarchaeological methodologies, unveils that alongside horses, donkeys were also among the animals transported by early English colonists but have remained historically undocumented until now.

The colonial records, primarily focused on horses, have long shaped historical narratives about animal introductions during early European settlements in America. However, this latest study, examining centuries-old equid remains excavated from Jamestown, challenges the completeness of these written accounts by identifying donkey bones that were previously overlooked. The research employs a combination of radiocarbon dating, ancient DNA (aDNA) analysis, and isotopic studies to not only affirm the presence of donkeys but also to trace their geographical origins and usage within the colony.

Researchers utilized meticulous zooarchaeological techniques to analyze wear patterns on the recovered bones, revealing signs consistent with bridling and labor use, suggesting that donkeys were valued as reliable working animals despite their absence from historical manifests. The isotopic signatures in tooth enamel and genetic markers demonstrate that these donkeys did not originate from Great Britain, as previously assumed for colonial livestock, but rather likely from regions along the settlers’ maritime route spanning Iberia, West Africa, and potentially even the Caribbean islands like Trinidad and Tobago.

Notably, the timing of the animal remains corresponds to the infamous “Starving Time” winter of 1609-1610, a period marked by severe hunger and hardship for the Jamestown settlers. The new findings elucidate a grim chapter in the colony’s history where both horses and donkeys were subjected to butchering and consumption. Bone fragment analysis revealed systematic processing, including splitting bones to extract marrow and dental pulp, highlighting the desperation experienced by colonists forced to rely on their livestock as a food source during the famine.

This study’s comprehensive approach integrates multiple lines of evidence—from osteological damage indicating usage and culling practices to biochemical assays that provide a window into the transatlantic animal trade networks and settlement survival strategies. It serves as a compelling example of how modern scientific technologies can expand historical knowledge beyond written texts, offering tangible insights into early colonial life and animal management practices that had remained obscured.

Senior author Dr. John Krigbaum, chair of anthropology at the University of Florida, emphasized the importance of zooarchaeology’s ability to uncover stories that historical documents omit, stating that these donkeys were likely crucial to the colony’s labor force despite no surviving records of their shipment. His team’s collaboration with experts in geological sciences, molecular anthropology, and archaeological chemistry has set a new standard for interdisciplinary research in historical archaeology.

The isotopic and genetic data suggest complex trade routes and animal exchanges that preceded and accompanied English colonial expansion. The donkeys’ potential origins in Iberia or West Africa, supported by isotopic similarities to regions around the Caribbean, underscore the dynamic nature of animal introductions during the early modern Atlantic world. These findings also hint at the broader ecological and cultural impacts brought about by the movement of domesticated animals across continents.

The study also opens new avenues for understanding how equids dispersed beyond initial colonial settlements into wild populations throughout the continent. The evidence suggests that donkeys, like horses, contributed significantly to the shaping of early American ecosystems and human-animal relationships, although their contributions have been largely overlooked until now.

Furthermore, the research highlights the dire conditions faced by Jamestown colonists, providing archaeological confirmation of survival strategies documented only sparsely in colonial narratives. The detailed analysis of bone fragmentation and cooking marks paints a vivid picture of the settlers’ grim reliance on every possible nutritional source during the colony’s most desperate moments.

Looking ahead, Dr. Krigbaum and his team aim to extend their research into other early colonial contexts, specifically targeting equid remains from the 16th-century Spanish settlement of Puerto Real in the Caribbean. This continued work promises to deepen historical understanding of how horses and donkeys influenced not just survival, but the social and economic foundations of New World colonial societies.

In sum, this landmark study not only revises historical assumptions but also exemplifies the power of multidisciplinary archaeological science to rewrite complex narratives of early colonial America. By tracing the overlooked histories of donkeys alongside horses, the research underscores the nuanced ways in which animal mobility and human survival intertwined in the Atlantic world’s formative centuries.

Subject of Research: Not applicable

Article Title: Early transatlantic movement of horses and donkeys at Jamestown

News Publication Date: 3-Sep-2025

Web References: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adw2595

Image Credits: Paula Calle Lopez, Courtesy of Jamestown Rediscovery (Preservation Virginia)

Keywords: Archaeology, Animal domestication, Archaeological sites, Historical archaeology