In a groundbreaking revelation that reshapes our understanding of early human activity in the Arabian Peninsula, an international team of archaeologists has uncovered a remarkable collection of monumental rock art panels situated along the southern boundary of the Nefud Desert in northern Saudi Arabia. These findings illuminate the adaptive strategies and cultural expressions of human groups who ventured into this harsh interior landscape shortly after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), a period characterized by extreme aridity and climatic challenge. The discovery highlights the return of seasonal water sources as a vital catalyst for human occupation and artistic creativity in this once forbidding environment.

This multidisciplinary research, known as the Green Arabia Project, brought together institutions including the Saudi Ministry of Culture’s Heritage Commission, the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), University College London, and Griffith University, among others. Their collaborative efforts revealed over 60 unprecedented rock art sites spanning three major locations: Jebel Arnaan, Jebel Mleiha, and Jebel Misma. These areas had remained unexplored until now, offering fresh insights into human resilience during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, roughly 12,800 to 11,400 years ago.

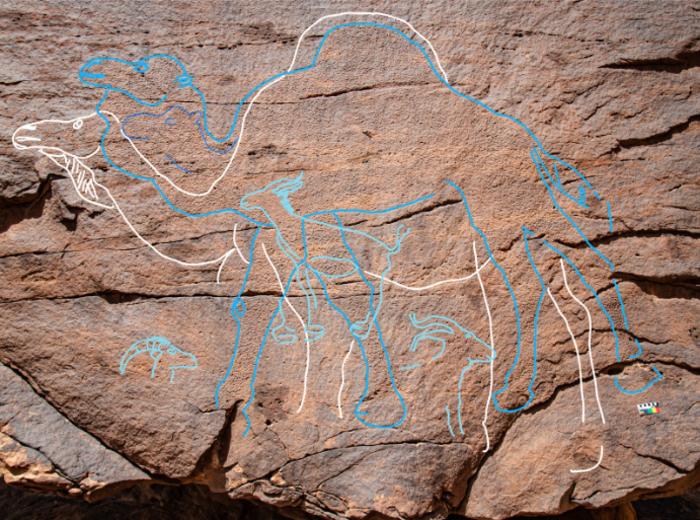

The panels contain an extraordinary total of 176 engravings, depicting a diverse array of fauna such as camels, ibex, equids, gazelles, and aurochs. Notably, about 130 of these figures are life-sized and rendered with naturalistic detail, with some reaching dimensions up to three meters in length and over two meters in height. This scale and sophistication suggest these images played a critical role beyond mere decoration, possibly serving as symbols of identity, territoriality, or social memory for the groups who created them.

Radiometric dating and sediment analysis underpin the timing of these engravings, placing them in the context of a climatic amelioration when ephemeral water bodies re-emerged across the desert interior. These hydrological shifts would have provided the necessary resources for humans to penetrate and occupy previously inaccessible or inhospitable zones. Water sources not only facilitated survival but also shaped movement and settlement patterns, as reflected by the strategic placement of the rock art itself.

Unlike previously documented Arabian rock art, which often features engravings hidden within secluded crevices, many of the panels at Jebel Arnaan and Jebel Mleiha are prominently etched on towering cliff faces, some soaring up to 39 meters high. This elevated positioning imbues the images with an imposing presence, visible over vast distances. One particularly striking panel would have demanded that ancient artists physically climb precarious ledges to execute their work, underscoring the profound cultural importance attributed to these visual statements.

Detailed artifact analysis further enriches the narrative, with recovered items including Levantine-style El Khiam and Helwan stone points, green pigment, and dentalium shell beads. These elements indicate extensive cultural and possibly trade connections between northern Arabian populations and the broader Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) communities of the Levant, highlighting a far-reaching network of interaction during this pivotal period of human history.

Despite these connections, the sheer scale, artistic approach, and dominant cliff-face locations of the Arabian rock art distinguish it from its Levantine counterparts. This unique symbolic language reflects a distinctive cultural identity meticulously adapted to the rigors of desert life. It speaks to a community capable of innovative responses to environmental challenges, leveraging the landscape’s features to mark presence and negotiate social landscapes.

“Far from being simple artistic expressions, these engravings likely functioned as enduring markers of human occupation, territorial claims, or cultural narratives,” explains Dr. Maria Guagnin of the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, the study’s lead author. The images’ imposing size and placement would have communicated messages across generations, symbolizing both survival and social cohesion in an unforgiving ecosystem.

Dr. Ceri Shipton from University College London, co-lead author, adds that the rock art represents a sophisticated mnemonic system, marking water sources and movement corridors. This interpretation positions the engravings as vital elements within an ancient communication network, encoding information crucial for navigating and exploiting the desert environment’s sparse resources.

The study also fills a critical gap in Arabian archaeology by bridging the temporal divide between the Last Glacial Maximum and the Holocene epoch. Previous research had largely overlooked this transitional interval when dramatic environmental and cultural transformations occurred. The Green Arabia Project’s interdisciplinary approach—melding archaeological excavation, geoarchaeological analysis, and iconographic study—provides a nuanced perspective on how early desert communities thrived through innovation and adaptability.

Dr. Faisal Al-Jibreen of the Saudi Ministry of Culture notes that this discovery reframes our understanding of Arabian desert prehistory. The monumental engravings signify a sophisticated cultural expression demonstrating resilience and agency rather than mere subsistence. It reveals the interior of northern Arabia not as an ecological void but as a dynamic cultural landscape shaped by human ingenuity.

The published research, entitled “Monumental rock art illustrates that humans thrived in the Arabian Desert during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition,” appears in the latest issue of Nature Communications. Its findings promise to inspire further exploration into the complexities of desert archaeology and the rich legacies of ancient human societies in marginal environments.

As ongoing investigations continue to unearth more evidence, the Arabian Peninsula emerges not only as a crucial corridor for human migration but also as a vibrant center of early symbolic behavior. This research challenges long-held assumptions about prehistoric desert life, reconstructing a picture of active, visually expressive communities that engaged intensely with their environment and each other.

Subject of Research: Human occupation and rock art in northern Arabia during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition.

Article Title: Monumental rock art illustrates that humans thrived in the Arabian Desert during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition.

News Publication Date: 2024.

Web References: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63417-y

References:

Guagnin, M., Shipton, C., Al-Jibreen, F., Petraglia, M. et al. (2024). Monumental rock art illustrates that humans thrived in the Arabian Desert during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63417-y

Image Credits: Maria Guagnin

Keywords: Arabian rock art, Pleistocene-Holocene transition, Last Glacial Maximum, Nefud Desert, prehistoric archaeology, human adaptation, prehistoric symbolic expression, environmental archaeology, Levantine connections, Green Arabia Project.