Why do individuals adhere to societal rules and cooperate with one another, and what are the consequences when those tasked with enforcing these rules stand to gain financially from their punitive actions? This profound question lies at the heart of a groundbreaking new study conducted by researchers at the University of California San Diego’s Rady School of Management. Published in the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the research reveals that introducing monetary incentives for punishment leads to a collapse in cooperation, even among those who would logically benefit from collaborative behavior.

The study challenges the long-standing assumption in behavioral science that the presence of punishment naturally fosters cooperative social norms. Traditionally, economic games designed to simulate social dilemmas have shown that when participants are able to punish selfish behavior at no personal gain, cooperation rates rise. However, by incorporating a crucial modification—allowing punishers to receive financial rewards—the researchers unveiled a startling reversal of this effect, thus destabilizing cooperation altogether.

At the core of this investigation lies a sophisticated variation of a classic experimental paradigm. More than four thousand participants engaged in an online economic game where they were assigned distinct social roles: “decision-makers,” “community members,” or “third-party punishers.” The decision-makers decided how to allocate a sum of money—sharing it with the community member or keeping it entirely for themselves. The third-party punishers then had the option to penalize decision-makers by reducing their financial gains, simulating real-world enforcement actions.

Under the classic version of this game, consistent with decades of research, the threat or application of punishment reliably increased the likelihood that decision-makers would share money, promoting cooperative behavior. This effect has often served as a microcosm for understanding how law and social order arise in human societies. Yet, when the experimenters introduced a financial incentive for third-party punishers—providing them with bonuses proportional to their punitive actions—the dynamic shifted dramatically.

The introduction of profitable punishment led to a significant decline in cooperation from the outset. Decision-makers increasingly chose to retain all their money, acting out of self-interest rather than fairness. Even when the parameters of the game were adjusted so that punishers could exclusively target selfish decisions—thereby minimizing ‘misfires’ or unfair punishment—the cooperation did not rebound. This suggests that the initial breach of trust created by the profit motive had enduring effects on participant behavior, fundamentally undermining social norms.

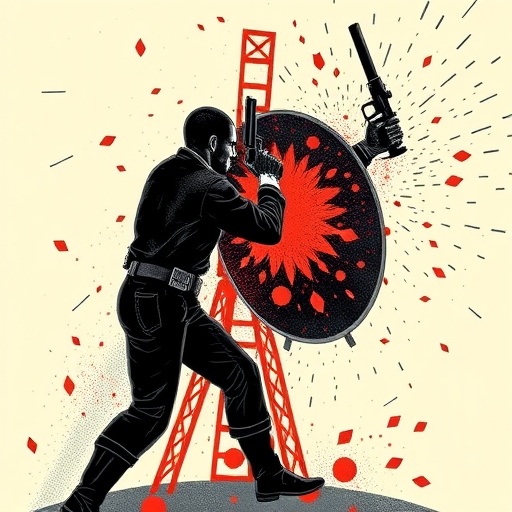

Such findings provide valuable insights into real-world social and legal systems where the enforcement of rules is entangled with economic incentives. Practices like private, for-profit prisons, policing based on arrest or citation quotas, and civil asset forfeiture—where authorities can seize property suspected of criminal connections without a conviction—embody precisely the model tested in the laboratory. In these contexts, trust in enforcers erodes as individuals suspect that punishments serve self-interest rather than communal justice.

The implications extend deeply into debates surrounding criminal justice reform. Severe punishments often fail to deter crime, a paradox that has perplexed researchers for years. This study offers a compelling explanation: when punishment becomes a tool of profit rather than an impartial means of maintaining social order, it fosters suspicion, leading to decreased cooperation with laws and increased social fragmentation. Furthermore, this cycle can create feedback loops, wherein distrust escalates punitive measures, which then further undermine social cohesion.

One particularly striking element unveiled by the research is the role of perspective in shaping attitudes toward punishment. Participants who imagined themselves as outsiders to the punitive system—those unlikely to be punished—were more trusting of punishers and more inclined to endorse harsh penalties, even when punishers benefited financially. Conversely, individuals who saw themselves as potential targets of punishment became skeptical and less likely to trust enforcement authorities, worried about fairness and impartiality.

This divergence helps explain the political dynamics surrounding “tough on crime” policies. Voters removed from the immediate consequences of aggressive law enforcement may overestimate its efficacy and fairness, failing to account for how such practices affect marginalized communities. The study highlights the critical importance of perspective-taking in social policy, suggesting that empathy for those under duress can shift public attitudes toward more just and effective criminal justice measures.

At its core, the research underscores that behavioral change is not merely about outcomes but about signaling genuine intent. Even the most rigorous and equitable enforcement mechanisms can fail if the individuals subjected to them lack trust in the system’s motives. Structural reforms that eliminate profit motives from punishment—such as abolishing quotas, ending civil asset forfeiture, and discontinuing for-profit incarceration—offer pathways to rebuild trust.

Measuring trust and cooperation through controlled economic games with actual monetary stakes allows researchers to isolate and examine human behavior uncoupled from existing prejudices about law enforcement. By simulating enforcement situations stripped of historical and social biases, the study unveils fundamental psychological mechanisms by which monetary incentives in punishment corrupt cooperative norms.

The consequences extend beyond academic theory. As debates over policing, incarceration, and community safety rage worldwide, this research calls for policymakers and communities alike to put trust-building at the forefront of reform efforts. By recognizing that trust—not punishment—is the cornerstone of any cooperative society, future justice systems can aim to restore legitimacy and mutual respect between citizens and enforcers.

Ultimately, this investigation reveals a troubling paradox: when enforcement agencies stand to profit from punishment, the very social contract they aim to uphold begins to dissolve. Cooperation, fairness, and social harmony falter in the absence of perceived moral integrity. To foster lasting social order, societies must confront and correct the structural incentives that undermine trust so fundamentally.

For those seeking to understand the fragile balance between incentive structures, social norms, and justice, this study provides crucial empirical evidence. Moving toward criminal justice policies predicated on transparency, fairness, and community trust rather than profit incentives may be essential in restoring cooperation and rebuilding frayed social fabrics. In an era marked by rising mistrust and polarization, such insights carry urgent relevance for governance and societal well-being.

Subject of Research: People

Article Title: Profitable Third-Party Punishment Destabilizes Cooperation

News Publication Date: 19-Aug-2025

Web References: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2508479122

References: Classic behavioral economic punishment research; real-world crime deterrence studies (links within article)

Keywords: Social research, Psychological science