A groundbreaking new study led by researchers at Dartmouth College has uncovered compelling evidence shedding light on the origins of pig domestication, tracing it back approximately 8,000 years to the Lower Yangtze River region in South China. This revelation not only offers profound insights into early human-animal interactions but also illustrates how behavioral adaptations preceded physical changes in the domestication process. The research published recently in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences moves beyond traditional morphological analyses and introduces innovative biomolecular techniques to reconstruct the dietary habits of ancient pigs, underpinning their gradual shift from wild boars to the familiar domestic pig.

For decades, the domestication of livestock has been primarily inferred through comparative skeletal examinations, where reductions in body size and changes in skull and teeth morphology were taken as key indicators. However, these phenotypic shifts are often lagging markers that occur well after the initial phases of domestication, which are distinguished by subtle behavioral alterations rather than overt anatomical transformations. The Dartmouth-led team challenged this paradigm by extracting and analyzing dental calculus—mineralized plaque—from 32 pig molar specimens excavated at two Neolithic sites, Jingtoushan and Kuahuqiao, both nestled in a waterlogged environment conducive to exceptional organic preservation.

The mineral deposit trapped on the teeth allowed researchers to identify microscopic food residues and parasitic entities, enabling a reconstruction of the animals’ diets and living conditions. The presence of a diverse assemblage of starch granules delineated a clear shift in foraging patterns: the pigs had consumed cooked human foods, including domesticated rice and yams, as well as acorns and various wild grasses. These findings provide irrefutable evidence that wild boars were not merely scavenging in the wilderness but were closely integrated into human settlements, surviving largely on refuse or direct feeding by people. This dietary integration likely triggered significant behavioral modifications, fostering tolerance and reduced aggression towards humans.

Intriguingly, the analysis also revealed eggs of the human-specific parasite whipworm (Trichuris), found embedded in the dental calculus of half the pig specimens examined. This points to an intimate ecological relationship wherein pigs ingested human fecal matter or consumed food and water contaminated with human excreta. This discovery is pivotal in understanding the zoonotic transfer of parasites and sheds light on the co-evolution of humans and domestic animals within early agrarian communities, where increasing sedentism intensified interspecies health dynamics.

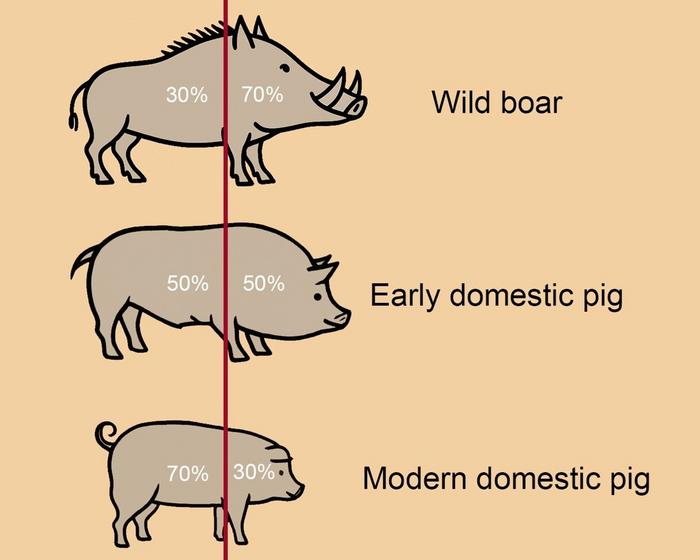

The study’s lead author, Jiajing Wang, assistant professor of anthropology at Dartmouth, explains that the domestication pathway observed here aligns with the "commensal pathway" model. In this scenario, wild boars independently ventured into burgeoning human villages attracted by abundant food waste, creating a mutualistic relationship that laid the groundwork for domestication. Over many generations, natural selection favored traits such as diminished aggression and increased sociability, traits that allowed these animals to coexist in close quarters with humans, leading ultimately to morphological modifications such as reduction in body and brain size.

Supporting this behavioral-close relationship, morphometric analyses comparing the dental structures of Jingtoushan and Kuahuqiao pig specimens revealed individuals with smaller molars resembling those of present-day domestic pigs. This morphological evidence, coupled with dietary and parasitic data, suggests an ongoing domestication process spanning both "commensal" and active "prey" pathways, where early humans may have begun selectively managing pig populations to exploit them as reliable food sources.

The study importantly clarifies the temporal and geographical contours of pig domestication in East Asia, a region that has long been suspected but lacked definitive biological proof of early domestic pig management. While rice cultivation at Kuahuqiao had been previously documented through starch residues on grinding stones and pottery, the direct evidence from pig dietary analysis stands as the first robust molecular fingerprint of animal domestication dating back to around 8,000 years ago. This timeline coincides with broader Neolithic transitions characterized by sedentism, agriculture, and profound shifts in human-environment relationships.

Beyond illuminating ancient human-animal dynamics, the findings have substantial implications for understanding the epidemiology of parasitic diseases in prehistoric communities. The direct consumption of human waste by pigs would have facilitated the transmission of parasitic worms, potentially exacerbating public health challenges in early villages. This underscores how domestication not only reshaped human economies but also their disease landscapes, highlighting a complex interplay between cultural innovations and biological consequences.

From a methodological standpoint, the application of microfossil analysis and dental calculus biomarker studies opens new avenues for archaeologists and biological anthropologists to unravel subtle behavioral thresholds in prehistoric animals. By focusing on dietary and microbiological signatures embedded in dental tissues, this interdisciplinary approach transcends the limitations of skeletal morphology alone, providing a more nuanced narrative of domestication that accounts for behavioral ecology, physiology, and zoonotic interactions.

Jiajing Wang and colleagues, including graduate student Yiyi Tang Guarini, and collaborators from Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Henan Museum, have collectively advanced our comprehension of prehistoric pig domestication. Their work stands as a testament to the profound insights achievable through the integration of archaeological context, molecular biology, and evolutionary anthropological frameworks.

This research not only fills a significant gap in the story of animal domestication but also emphasizes the importance of understanding human cultural evolution through the lens of animal behavior and ecology. By elucidating the subtle steps through which wild boars slowly adapted to anthropogenic environments, it rewrites the story of domestication as a protracted, complex process shaped by ecological opportunities and behavioral plasticity rather than abrupt physical modification.

The team’s findings continue to open exciting pathways for future research, suggesting that similar biomolecular investigations in other species and regions may reshape our perspectives on domestication, cohabitation, and the intertwined fates of humans and animals across millennia.

Subject of Research: Pig domestication process in Early Neolithic South China

Article Title: Early evidence for pig domestication (8,000 cal. BP) in the Lower Yangtze, South China

Web References:

Image Credits: Artwork by Jiajing Wang.

Keywords: Anthropology, Domesticated animals, Pigs, Archaeology