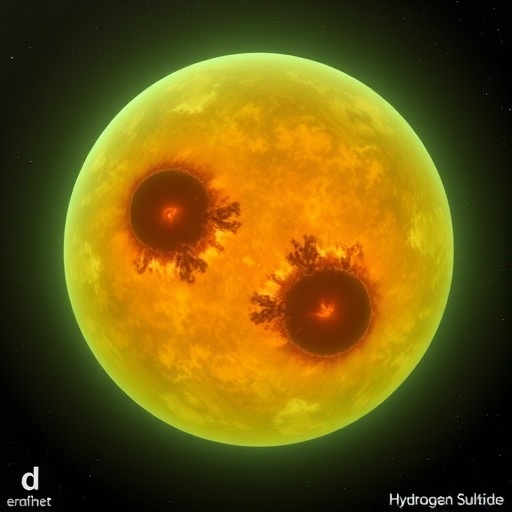

Hydrogen sulfide, a gas notorious for its characteristic rotten egg smell, is making headlines in an unexpected context: the atmospheres of four distant gas giant planets. This groundbreaking discovery by astronomers from UCLA and the University of California, San Diego, marks the inaugural identification of hydrogen sulfide beyond our solar system. Moreover, the innovative techniques employed in this research are anticipated to significantly enhance the search for extraterrestrial life across the universe.

Gas giants such as Jupiter and Saturn are primarily composed of hydrogen and helium, alongside a dense core. Their formation is a fascinating process that unfolds in a rotating disk of dust and gas surrounding a nascent star. While typically considered large planets, gas giants can occasionally blur the lines between planets and stars. This is particularly evident when it comes to brown dwarfs, which are substellar objects that can form similarly to stars but do not reach the mass necessary for nuclear fusion. However, astronomers have recently identified brown dwarfs that fall below the 13 Jupiter mass threshold, illustrating the ambiguous boundaries that exist while classifying celestial objects of these intermediate mass ranges.

Jerry Xuan, a postdoctoral researcher at UCLA and a co-author of the paper published in Nature Astronomy, underscores the fluidity of definitions surrounding stellar and planetary formation. The established threshold for brown dwarfs is an arbitrary figure, lacking a strong foundation in our understanding of the complexities involved in such formations. The ongoing research aims to extend our grasp of these phenomena, particularly focusing on four massive gas giants revolving around the star HR 8799, situated about 133 light-years away in the constellation Pegasus.

The gas giants within this system are diverse in size, with the smallest about five times the mass of Jupiter and the largest approximately ten times as massive. These planets are situated exceptionally far from their star, with the nearest planet located at a distance 15 times greater than that between Earth and the Sun. The significant separation raises questions regarding their formation. For a considerable period, the categorization of these bodies as either planets or brown dwarfs remained uncertain, reflecting the ongoing complexity surrounding massive planetary formation.

In this landmark study, the UCLA and UCSD team utilized spectral data acquired from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to detect hydrogen sulfide within the atmospheres of these distant planets. This advanced observational technique operates based on the principle that different chemical molecules absorb and emit light at specific wavelengths. By studying the light spectra, scientists can determine the elemental composition of the planets’ atmospheres, revealing the presence of specific gases like hydrogen sulfide.

Given that these planets are approximately 10,000 times fainter than their surrounding star, the research team faced the daunting challenge of extracting subtle signals from the JWST data. Jean-Baptiste Ruffio, a research scientist at UCSD and one of the paper’s co-authors, developed novel data analysis techniques to enhance the clarity of these observations. Jerry Xuan also contributed by creating intricate atmospheric models, enabling precise comparisons with the JWST spectra to ascertain the presence of sulfur in the planets’ atmospheres.

The detection of hydrogen sulfide suggests that sulfur was incorporated into the planets as solid matter during their formation. This solid matter, originating from the surrounding protoplanetary disk, combined with the extremely high temperatures in the growing planets’ cores and atmospheres, led to the evaporation of solid materials into gaseous sulfur. This mechanism is vital for understanding how gas giants accumulate elements and how their atmospheric compositions can differ dramatically from their host stars.

The ratio of sulfur to hydrogen discovered is notably higher than that found in the central star, indicating a significant divergence in composition. This unique enrichment pattern mirrors similar observations made in Jupiter and Saturn, prompting researchers to ponder whether there exists a universal process governing the formation of celestial bodies. The findings suggest that, within the environment of these distant gas giants, it is natural for them to acquire heavy elements in roughly equal proportions, showcasing an intrinsic order in the chaotic interplay of stellar formation.

Ruffio points out that the HR 8799 system stands out as the only currently imaged system with four massive gas giants. However, there exist other planetary systems housing one or two even larger companions, their formation mechanisms still shrouded in mystery. These queries have prompted astronomers to contemplate the upper limits of planetary size, igniting discussions on whether a planet could exist at 15, 20, or even 30 times the mass of Jupiter and still form as a planet rather than transitioning to brown dwarf status.

Xuan emphasizes the implications of this research for the ongoing quest to discover Earth-like exoplanets. The methodology applied—enabling researchers to visually and spectrally distinguish planets from their stars—holds great promise for studying distant exoplanets in detail as technological capabilities advance. Presently, this approach is constrained to gas giants, but, with the development of greater telescopic power and improved instruments, it is envisioned that similar techniques could be adapted for investigating terrestrial planets.

The dream of identifying an Earth analog represents the “holy grail” for exoplanet research; however, Xuan cautions that this goal may still be decades away. It is feasible that in 20 to 30 years, scientists may successfully capture the spectral signature of an Earth-like planet and begin the search for potential biosignatures, such as oxygen and ozone within its atmosphere. These future developments hinge on the continued evolution of astronomical research and technology, with the current study paving the way for understanding complex planetary systems beyond our solar system.

The research has been supported by NASA, highlighting the collaborative effort in unraveling the mysteries of our universe. As astronomers continue to peel back the layers of cosmic formation, discoveries such as these will inevitably reshape our comprehension of the cosmos and our place within it.

Subject of Research: The detection of hydrogen sulfide in distant gas giant planets’ atmospheres and its implications for planetary formation.

Article Title: The Discovery of Hydrogen Sulfide in Distant Gas Giants: Implications for the Origins of Planets

News Publication Date: October 2023

Web References: [Not available]

References: [Not available]

Image Credits: [Not available]

Keywords

Hydrogen sulfide, gas giants, exoplanets, planetary formation, James Webb Space Telescope, HR 8799, stellar formation, brown dwarfs, NASA, celestial chemistry.