The intricate relationship between motor dysfunction, social context, and the early prodromal features of psychosis has long fascinated neuroscientists and psychiatrists alike. In a groundbreaking study, Waddington (2025) illuminates the historical acumen, developmental pathobiology, and the promise of early intervention strategies targeting these interwoven factors. As psychotic disorders continue to pose significant challenges globally, understanding their earliest manifestations and underlying mechanisms can transform both diagnosis and treatment.

Historically, the recognition of motor abnormalities in psychiatric disorders dates back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when pioneers observed subtle motor signs in individuals predisposed to schizophrenia. These early observations, though primitive by today’s standards, hinted at a neurodevelopmental origin, suggesting that motor dysfunction might not merely be a symptom but a prodrome, or early indicator, of psychosis. Waddington’s review emphasizes that this historical acumen, built from clinical observations and careful longitudinal studies, sets the stage for modern research that integrates neurobiology with behavioral science.

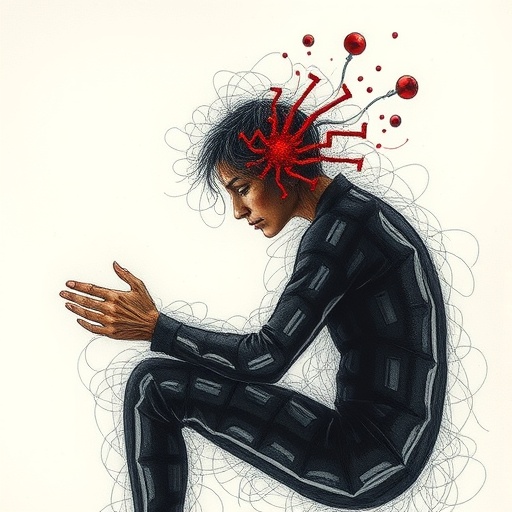

Central to this discourse is the concept of prodromal features—the subtle symptoms and signs that precede the onset of full-blown psychosis. Motor dysfunction emerges as a consistently replicated prodromal marker, ranging from impaired fine motor skills to abnormal gait and increased neuromotor associated abnormalities. These motor signs are not isolated phenomena but manifest within the broader social context of the individual, interacting dynamically with social functioning and environmental stressors.

Developmental pathobiology offers critical insights into why and how motor dysfunction and prodromal symptoms intersect. Neurodevelopmental disturbances stemming from genetic predispositions, prenatal adversities, and early-life environmental insults disrupt critical brain circuits responsible for motor control and cognitive function. Waddington expertly delineates how alterations in cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical loops, together with aberrant synaptic pruning during adolescence, underlie both motor and psychotic symptoms. These developmental threads illuminate the tangled web linking early neural disruptions to later clinical outcomes.

The social context cannot be overstated when considering prodromal psychosis. Social isolation, stigma, and impaired social cognition exacerbate vulnerability, often compounding subtle motor dysfunction into significant functional impairment. Waddington argues persuasively that a failure to account for social determinants risks oversimplifying the prodrome and may lead to missed opportunities for early detection and intervention.

A pivotal challenge lies in translating these complex neurodevelopmental insights into clinical practice. Early intervention hinges on the identification of reliable biomarkers and prodromal features that are accessible in everyday clinical settings. Motor dysfunction, measurable through standardized neurological examinations or increasingly sophisticated technologies such as motion capture and wearable sensors, offers a promising adjunct to traditional psychiatric assessments.

Furthermore, Waddington presents compelling evidence that targeted early interventions—ranging from pharmacological strategies to cognitive-behavioral therapies and social skills training—can attenuate or even alter the trajectory of psychotic disorders. Importantly, interventions aimed at improving motor function and social integration could synergistically delay or prevent the onset of psychosis, fostering better long-term outcomes.

The paper also addresses the ethical considerations inherent in labeling at-risk individuals. While early identification is critical, there is an unavoidable risk of stigma and potential over-medicalization. Waddington advocates for a balanced approach that prioritizes informed consent, continuous monitoring, and supportive interventions that empower rather than marginalize individuals.

Waddington’s review integrates data from neuroimaging studies that depict structural and functional brain changes correlated with motor anomalies in prodromal states. Reduced gray matter volume in motor-related cortical areas, irregularities in basal ganglia connectivity, and dysregulated neurotransmitter systems such as dopamine and glutamate form a convergent neurobiological model explaining early manifestations of psychosis.

In addition to the neurobiological perspective, the study underscores advances in computational approaches and machine learning algorithms that analyze motor behavior data, generating predictive models of psychosis risk. This technological frontier promises to refine diagnostic specificity, enabling personalized intervention strategies that consider the gradations of motor abnormalities across individuals.

Waddington’s discussion extends into developmental timing, highlighting adolescence as a critical window during which neurodevelopmental derangements and environmental stress converge to produce prodromal signs. This temporal focus advocates for early screening programs in schools and primary care settings, capitalizing on neuroplasticity for preventive care.

The implications of this comprehensive framework reach beyond schizophrenia. Motor dysfunction and social difficulties are shared features across various neuropsychiatric conditions, suggesting a transdiagnostic relevance. Recognizing the overlapping developmental pathways may foster integrative intervention platforms targeting multiple early-onset disorders simultaneously.

Importantly, social determinants such as family environment, socioeconomic status, and cultural context modulate prodromal presentations and response to interventions. Waddington’s emphasis on multidisciplinary research incorporating sociological methods reflects a paradigm shift toward holistic models of mental health care.

The study concludes on an optimistic note, envisioning a future wherein motor dysfunction serves not only as an early warning signal but as a modifiable target that, when addressed in conjunction with social interventions, could reshape the landscape of psychosis prevention. This synthesis underscores the need for sustained collaboration among neuroscientists, clinicians, and social scientists.

Emerging questions persist: How best to scale early detection programs universally? What role might digital health tools play in continuous monitoring? How can health systems mitigate disparities in access to early intervention? Waddington’s work lays a foundation to tackle these challenges, inviting innovation and concerted efforts.

In the final analysis, the review exemplifies how blending historical insights, developmental neurobiology, and social sciences enrich our understanding of psychosis. It charts a transformative path from recognition of subtle motor dysfunctions within prodromal stages to integrated early interventions that may one day prevent the onset of debilitating psychotic illness altogether.

Subject of Research:

Motor dysfunction, social context, and early prodromal features of psychosis, integrating historical perspectives, developmental pathobiology, and early intervention.

Article Title:

Motor dysfunction, social context and early prodromal features of psychosis: historical acumen, developmental pathobiology and early intervention

Article References:

Waddington, J.L. Motor dysfunction, social context and early prodromal features of psychosis: historical acumen, developmental pathobiology and early intervention. Schizophr (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00704-z

Image Credits:

AI Generated