In an unprecedented turn within climate science, new research has revealed the potential for sea levels to fall significantly along coastal Greenland throughout the 21st century—a projection that contrasts the prevailing global narrative of relentless sea-level rise. This groundbreaking study, conducted by Lewright, Austermann, Piecuch, and colleagues, offers detailed projections that challenge established expectations and underscore the complex regional variations induced by ice sheet dynamics and gravitational effects.

At the core of this remarkable finding lies the interaction between the melting Greenland Ice Sheet and regional sea-level responses governed by gravitational and earth deformation processes. Traditionally, rising global temperatures have been expected to universally elevate sea levels as ice melts into the ocean. However, when the Greenland Ice Sheet loses mass, the gravitational pull it exerts on the surrounding ocean decreases, causing local sea levels adjacent to Greenland to actually drop. This nuanced interplay is central to the team’s sophisticated modeling efforts.

Employing an advanced suite of coupled climate and earth system models, the researchers combined ice-sheet melt projections with gravitational, rotational, and deformational (GRD) feedback mechanisms to simulate regional sea-level variability with unprecedented precision. Unlike previous studies that largely assumed uniform sea-level rise, this approach illuminated how local factors dramatically modulate the net impact of ice loss, especially in the vicinity of large ice masses such as Greenland.

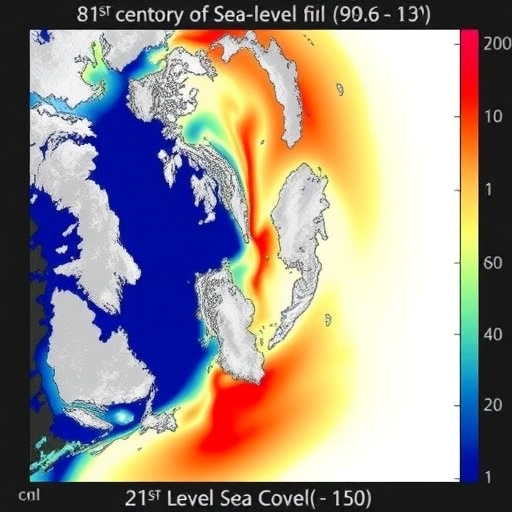

The findings reveal a consistent pattern: as the ice sheet sheds mass through surface melting and iceberg calving, the local ocean surrounding Greenland experiences sea-level falls reaching up to tens of centimeters by 2100. This response is predicted even under high-emission scenarios, defying the broader expectation that coastal regions worldwide will uniformly suffer from inundation. Intriguingly, the sea-level fall is sharpest nearest the ice margins and gradually transitions to rising waters further afield, demonstrating the highly non-linear spatial nature of sea-level change.

One of the pivotal advances of this research lies in its incorporation of self-consistent coupling between the ice sheet’s evolution and the solid Earth’s viscoelastic response. As the ice load lessens, the crust beneath Greenland rebounds slowly, pushing water away and further exacerbating localized sea-level drop. This feedback loop has not been adequately captured in earlier modeling efforts, highlighting how deep-time geological processes influence present-day hazards.

Moreover, the study accounts for rotational feedbacks caused by the redistribution of mass from the ice to the ocean. Changes in Earth’s spin axis and rotation rate subtly alter how ocean water is distributed circumglobally. Although these effects are small, their integration is critical for high-fidelity predictions, especially near regions affected by large ice-mass losses such as Greenland.

A significant implication of these projections is the pressing need to rethink regional risk assessments and adaptation strategies for coastal Greenland communities. While retreating sea levels may initially reduce local flood risks, the underlying ice sheet loss remains a harbinger of far-reaching environmental changes, including ecosystem destabilization and altered ocean circulation patterns. This duality paints a complicated picture for policymakers and residents alike.

The research further explores the temporal evolution of these sea-level changes, noting a non-monotonic trajectory. Initial decades may see modest sea-level rises due to thermal expansion and distant ice losses, followed by accelerated fall as Greenland ice melt intensifies and geophysical feedbacks strengthen. The timing and magnitude of these phases depend critically on future greenhouse gas emissions and ice-sheet dynamics—both characterized by substantial uncertainty.

To bolster confidence in their projections, the authors juxtaposed model outputs with observed data, including satellite gravimetry and tide gauge records, providing compelling validation for the realism of their coupled modeling framework. This empirical anchoring enhances the study’s credibility amidst often contentious discussions surrounding future sea-level trajectories.

Importantly, the study emphasizes that Greenland’s sea-level fall does not offset global sea-level rise but rather complicates its spatial pattern. Coastal regions remote from large ice sheets continue to face rising seas, exacerbating hazards such as storm surges and chronic flooding. Hence, a nuanced understanding of regional variability is crucial for effective climate resilience planning across diverse geographies.

From a technical perspective, this research exemplifies the frontier of cryosphere-climate modeling by employing an integrative approach that transcends single-domain studies. By synthesizing glaciology, geophysics, and oceanography, the researchers offer a holistic perspective that captures emergent system behaviors otherwise missed by isolated disciplinary frameworks.

This investigation also opens exciting avenues for future work, suggesting the critical importance of expanding similar coupled analyses to Antarctica and smaller glacier systems worldwide, where analogous gravitational and solid Earth feedbacks may yield intricate regional sea-level responses. Such comprehensive evaluations are indispensable for refining global hazard forecasts.

Furthermore, the study’s insights hold significant implications for satellite mission design and observational strategies. Improved monitoring of earth deformation and gravitational fields around ice sheets will be vital to track ongoing changes and validate model predictions, thereby facilitating real-time assessment of evolving sea-level risks.

In light of these revelations, this study stands as a clarion call for climate scientists and policymakers to embrace complexity and regional specificity in sea-level research. Recognizing that sea-level change is spatially heterogeneous, dictated by a maelstrom of physical processes, is essential for crafting robust adaptive measures amid an increasingly dynamic Earth system.

Ultimately, the 21st-century projections reported by Lewright and colleagues remind us that climate impacts are multifaceted and regionally divergent. Appreciating this nuance not only enriches scientific understanding but also empowers more effective, locally tailored responses to one of humanity’s most formidable environmental challenges.

Subject of Research: Projections of sea-level changes along coastal Greenland in the 21st century, focusing on ice-sheet melt-induced regional sea-level fall.

Article Title: Projections of 21st-century sea-level fall along coastal Greenland.

Article References:

Lewright, L., Austermann, J., Piecuch, C.G. et al. Projections of 21st-century sea-level fall along coastal Greenland. Nat Commun 17, 353 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68182-6

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68182-6