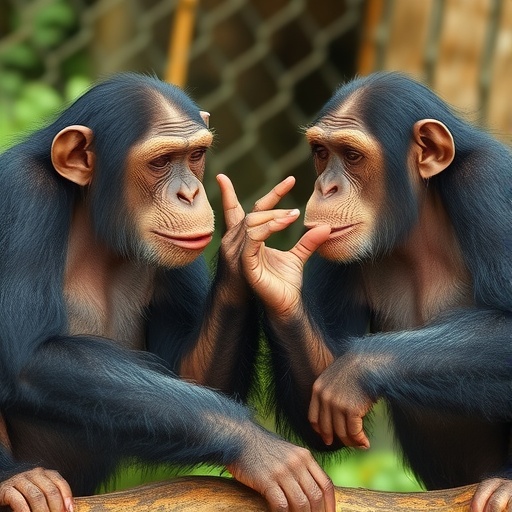

In a groundbreaking study shedding new light on chimpanzee communication, researchers have unveiled that young chimpanzees acquire their distinct methods of communication predominantly from their mothers and maternal relatives. This remarkable discovery challenges longstanding assumptions about the genetic determinism of communicative behavior in our closest living relatives. Published on August 5th in the prestigious open-access journal PLOS Biology, the research by Joseph Mine and colleagues from the University of Zurich and collaborators across Europe and the United States offers profound insights into the social learning mechanisms that shape vocal and non-vocal communication in wild chimpanzees.

Human communication is a complex interplay of vocal signals, gestures, facial expressions, and postures, largely influenced by early life interactions with caregivers. Until now, the extent to which these traits are culturally transmitted versus genetically inherited has been debated within primatology. Chimpanzees, sharing about 98% of our DNA, employ an equally diverse set of communicative signals, yet the origins—learned or innate—of these behaviors have remained elusive. By focusing on wild chimpanzees in Kibale National Park, Uganda, Mine’s team sought to unravel whether the nuances of their communicative styles arise through social learning or genetic predisposition.

The study monitored 22 habituated chimpanzees over significant periods, meticulously recording both vocalizations such as grunts, barks, and whimpers, alongside non-vocal cues including arm movements, gaze directions, and body postures. Using an integrative analytical approach, the researchers quantified how these signals combined within individuals. Strikingly, patterns emerged revealing that offspring shared a marked similarity in communication styles with their mothers and maternal kin, but not with fathers or paternal kin. This differential indicates that maternal influence, not paternal genetics, predominantly shapes communicative behavior.

Such findings are particularly compelling given chimpanzee social structure, where maternal care is intensive and prolonged, whereas paternal involvement in offspring rearing is minimal or absent. Thus, the transmission of communication style aligns more with social exposure and learning opportunities than strict genetic inheritance. The offspring appear to internalize and replicate the multimodal communication behaviors exhibited by their mothers, highlighting the vital role of maternal interaction in the developmental trajectory of communicative competence.

Importantly, all observed individuals were older than ten years—an age marking increasing independence from their mothers—signaling that maternally derived communication patterns endure well beyond early childhood. This persistence suggests that social learning mechanisms engrain communication styles deeply, potentially affecting social dynamics and cohesion throughout the chimpanzee’s lifespan. Consequently, these results offer new perspectives on the evolutionary origins of communication, proposing that the capacity for social learning in vocal and visual signals is more ancient and fundamental than previously acknowledged.

In a direct statement, lead author Joseph Mine emphasized the variability observed across chimpanzee families, noting how “certain chimpanzee mothers tend to produce many vocal-visual combinations, while others produce few. And the offspring end up behaving like the mothers, resulting in family-specific tendencies.” This insight signifies the potential for diverse communication cultures within wild chimpanzee populations, shaped by nuanced maternal influence rather than rigid genetic codes.

Simon Townsend, co-author of the study, further elaborated on the sophistication of the research approach. He explained that “in humans, body language includes hand gestures and facial expressions, but also many subtle behaviours, like shifts in posture and gaze direction. With our approach, we were able to assess whether chimpanzees learn about these less salient features as well.” Such an innovative methodology underscores the intricacy of primate communication and the subtlety through which social learning guides communicative behaviors.

Katie Slocombe, another co-author, expressed enthusiasm about future directions stemming from the research, “I think it’s fascinating that mothers who produce more visual behaviours when they vocalise, raise offspring that follow suit. The next exciting step will be to see if offspring are learning certain types of visual-vocal combinations from their mothers, in addition to the number of visual behaviours they produce when they vocalise.” This prospect opens thrilling avenues into understanding how complex communicative repertoires evolve and diversify within primate societies through social transmission.

More broadly, the implications of this research extend beyond chimpanzees, offering valuable comparative insights into the evolutionary pathways that led to human language and communication. It suggests that the building blocks for culturally transmitted multimodal communication systems exist deeply embedded in primate heritage. Recognizing that social learning plays a distinct and dominant role in shaping communication encourages a reevaluation of how language may have emerged through incremental adaptations grounded in social interactions.

The study was funded through multiple esteemed sources, including the Swiss National Science Foundation, the European Research Council, and the National Science Foundation in the United States, underpinning its robust scientific foundation. It epitomizes a high-caliber international collaboration committed to advancing understanding of animal cognition and communication.

For those interested in exploring the full detailed findings, the paper is freely accessible in PLOS Biology at http://plos.io/4lsNJkO. This open access ensures that scientists, educators, and the public alike can engage with cutting-edge research illuminating the profound social complexity of chimpanzee communication.

This research represents a significant step forward in animal communication studies, revealing that the style and structure of how chimpanzees communicate are less a matter of inherited biology and more a result of dynamic social learning influenced by maternal kin. These revelations not only enrich primatology but also deepen our appreciation for the shared roots of social behavior and communication in the animal kingdom.

Subject of Research: Animals

Article Title: Chimpanzee mothers, but not fathers, influence offspring vocal–visual communicative behavior

News Publication Date: August 5, 2025

Web References:

- Full paper: http://plos.io/4lsNJkO

- DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3003270

References:

Mine JG, Dees LC, Wilke C, Willems EP, Machanda ZP, Muller MN, et al. (2025) Chimpanzee mothers, but not fathers, influence offspring vocal–visual communicative behavior. PLoS Biol 23(8): e3003270.

Image Credits: Ray Donovan (CC-BY 4.0)

Keywords: Chimpanzee communication, social learning, vocal-visual signals, primate behavior, maternal influence, multimodal communication, animal cognition, evolutionary biology