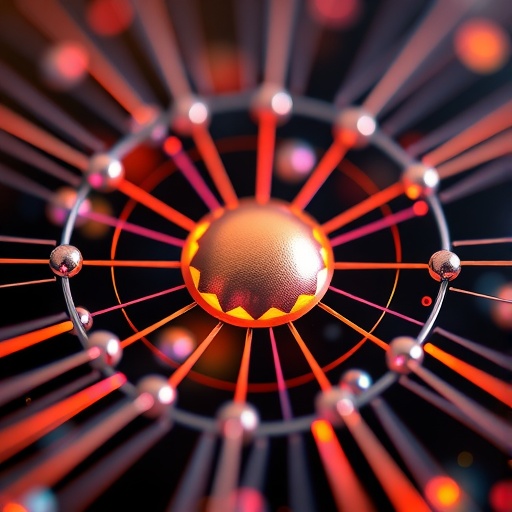

In a groundbreaking advancement poised to reshape the landscape of quantum technology and photonics, researchers at Harvard’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences have unveiled a novel fabrication method for producing ultra-smooth, microscopic mirrors. These mirrors are engineered to form exceptionally high-performance optical resonators, or microcavities, that operate with unprecedented finesse and precision. By leveraging silicon’s intrinsic properties combined with mechanical stress induced by meticulously designed dielectric coatings, this innovative technique produces micro-mirrors that buckle into perfectly curved configurations, enabling the confinement and control of light at near-infrared wavelengths. This work not only represents a significant leap in optical cavity design but also offers promising pathways for scalable quantum networks, integrated lasers, and ultra-compact sensing technologies.

The principle behind optical resonators, often referred to as optical cavities, is analogous to that of a guitar string: only certain wavelengths of light can be sustained and amplified between two highly reflective mirrors. These resonators are foundational to numerous photonic devices including lasers, precision clocks, and spectroscopy instruments. However, the burgeoning field of quantum computing demands optical cavities that are much smaller, exhibit extraordinarily low signal loss, and can precisely interact with single photons and atoms. Traditional fabrication methods—relying heavily on lithography and etching—have been unable to deliver mirrors with the surface smoothness necessary for these exacting applications. This barrier has spurred the Harvard team, led by electrical engineering expert Marko Lončar and physics luminary Mikhail Lukin, alongside assistant professor Kiyoul Yang, to reimagine microcavity manufacturing through a fundamentally different and more efficacious mechanism.

Central to this breakthrough is a microfabrication strategy inspired by the behavior of thin-film materials under stress. The process begins with a silicon wafer, upon which a layer of silicon oxide is thermally grown. This oxide layer acts as a smoothing agent, evening out nanoscale roughness through its growth-and-removal cycle, thus yielding an exceptionally flat silicon surface—a critical prerequisite for high optical quality. Upon this flat substrate, the researchers deposit a carefully engineered stratified stack of transparent oxide layers, termed a dielectric mirror coating. This multilayer coating is precisely tailored both structurally and optically to define the mirror’s curvature and reflectivity at target wavelengths.

Subsequent etching of circular holes through the silicon wafer’s backside liberates the dielectric coating locally, allowing the built-in mechanical stress to naturally cause the freed membranes to buckle into smoothly curved mirrors with high accuracy and repeatability. This buckling self-assembly circumvents the complications and surface defects typically introduced by direct lithographic patterning or surface shaping techniques. The radius of curvature of these micromirrors can be meticulously controlled by tuning the intrinsic stress and layer thicknesses, offering an unprecedented level of customization and scalability, essential for mass production and integration into complex photonic systems.

The team demonstrated that optical cavities formed by pairing two of these buckled micromirrors exhibit outstanding finesse, achieving a value of approximately 0.9 million at a wavelength of 780 nanometers. To contextualize, finesse is a measure of how many times light bounces between mirrors before dissipating, and this extraordinarily high number signifies minimal scattering and loss inside the cavity. This wavelength is particularly significant for quantum technology applications, as it aligns with the optical transition frequencies of ultracold rubidium atoms commonly used in quantum networking and computing experiments. The capability to sustain light within a tiny volume for so long enhances the strength of atom-photon interactions, a cornerstone for efficient quantum information processing.

This novel microcavity fabrication technique addresses a persistent challenge faced by experimental quantum physicists: developing photonic interfaces that enable robust and fast coupling between individual photons and atomic quantum states. Such coupling is essential for constructing scalable quantum networks where information encoded in atomic states can be transferred and transmitted via light, with applications ranging from distributed quantum computing to ultra-secure quantum communication. The cavities created using this method could serve as modular building blocks that interlink arrays of atoms through photonic channels, dramatically expanding the scale and complexity of quantum architectures.

Moreover, the versatility of this buckled microcavity design holds promise beyond quantum systems. Its intrinsic scalability and tunability make it a strong candidate for integration into chip-scale photonic devices, including ultra-compact lasers, high-resolution spectrometers, and environmental sensors. Operating over customizable wavelengths means that these microcavities can be adapted for a variety of applications ranging from telecommunications at 1550 nanometers to emerging optoelectronic systems requiring nanophotonic precision. Their integration into silicon-based platforms is especially advantageous for future photonic circuits seeking to combine optical and electronic functionalities on a single chip.

In terms of fabrication infrastructure, this research capitalized on the advanced capabilities of Harvard’s Center for Nanoscale Systems, a facility equipped for the precise nanoscale engineering essential for silicon-based device production. The use of thermal oxidation to smooth the silicon substrate, coupled with the deposition of multilayer dielectric coatings and backside etching, exemplifies a synthesis of mature semiconductor processing techniques with creative strain engineering. This synergy enables not only the creation of superior microcavities but also signifies a paradigm shift in how mechanical stress can be harnessed as a tool for shaping photonic components instead of being merely a fabrication challenge.

The impact of this work resonates through multiple disciplines, elegantly bridging applied physics, materials engineering, and quantum science. By exploiting fundamental material properties rather than relying on incremental improvements in lithographic resolution or polishing methods, this approach exemplifies innovation through material design—where the mechanical, optical, and structural properties are co-optimized to realize devices invisible before to conventional fabrication constraints. The insights garnered here could stimulate new lines of inquiry in nanophotonics and optomechanics, domains crucial for the next generation of sensory, computational, and communication technologies.

As quantum computing continues its transition from theoretical promise to practical reality, components such as these high-finesse buckled microcavities will be indispensable. They enable the kind of photon-atom interfaces that are vital for quantum repeaters, error-correcting quantum networks, and scalable quantum information processing. Their development represents a leap forward in photonic engineering—one that integrates the subtleties of material science with the precision demands of quantum optics. By re-envisioning how microstructures can self-assemble into functional optical elements, the researchers have charted a course toward devices that are not only performance optimized but also feasible for widespread technological deployment.

The publication detailing this research appeared in the journal Optica, highlighting the collaborative synthesis of expertise from multiple Harvard laboratories. The paper, authored by Sophie Ding and colleagues, including Brandon Grinkemeyer and G.E. Mandopoulou, underscores the integral role of interdisciplinary collaboration in tackling complex challenges at the quantum frontier. This project received support from prominent institutions such as the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation, the Center for Ultracold Atoms, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research—testament to the broader scientific and strategic importance of this microcavity innovation.

In sum, the introduction of high-finesse buckled microcavities ushers in a new epoch in photonics and quantum technology. By translating subtle mechanical stress effects into engineered optical precision, the Harvard team has unlocked a pathway toward scalable, high-performance optical resonators tailored for the quantum age. The reverberations of this work will be felt across domains where light and matter must be united with exquisitely controlled interaction, setting the stage for the next wave of transformative quantum applications and optical devices.

Subject of Research: Not applicable

Article Title: High finesse buckled microcavities

News Publication Date: 11-Feb-2026

Web References: DOI: 10.1364/OPTICA.582994

Image Credits: Brandon Grinkemeyer / Lukin lab at Harvard

Keywords: Optics, Applied physics, Applied optics, Light sources, Optical devices, Photonics, Optoelectronics, Nanophotonics, Photonic crystals, Ion trapping, Engineering, Materials engineering, Fabrication, Microfabrication, Nanofabrication, Nanolithography, Materials processing, Microstructures, Quantum optics, Optical trapping, Optical properties, Quantum mechanics, Quantum computing