Over the past century, the location of long-term infrastructure such as fossil fuel power plants has become a focal point in environmental justice conversations. While much of the discourse has centered around the equitable placement of these facilities, comprehensive understanding of their long-term social and demographic consequences has remained elusive. A groundbreaking new study sheds light on how demographic shifts over decades following the establishment of fossil fuel plants crucially influence present-day disparities in environmental exposure, particularly within Black communities in the United States.

This study represents a collaborative effort among researchers from Carnegie Mellon University, Arizona State University, Université de Montréal, and Boston College. By exploiting newly digitized records documenting the siting and operations of power plants spanning from 1900 to 2020, coupled with granular demographic data from the U.S. Census dating as far back as 1870, the team conducted an unprecedented longitudinal investigation into the socio-environmental dynamics shaped by decades-old infrastructure decisions.

Traditionally, policies addressing power plant siting have focused on mitigating immediate environmental inequalities, often assuming that the initial placement of such plants would determine long-term demographic patterns and exposure risks. However, the researchers’ findings challenge this assumption by demonstrating that siting decisions alone do not account for the current distribution of racial disparities surrounding fossil fuel power plants. Instead, demographic movements and population changes occurring after plants become operational play a dominant role in shaping ongoing environmental inequality.

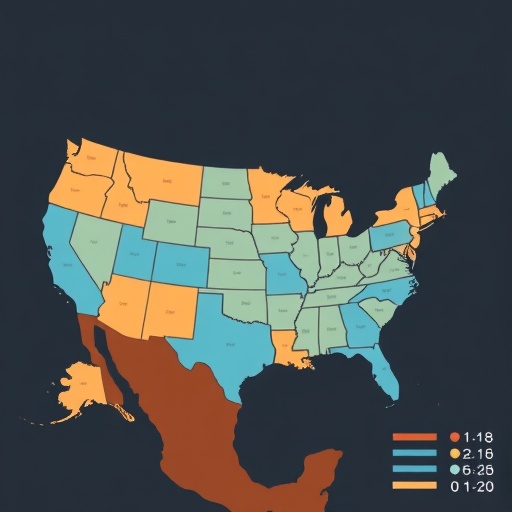

Contrary to common perceptions, the evidence does not indicate a systematic pattern of power plants being placed disproportionately in counties with higher Black populations during the period of active siting. Instead, siting decisions were primarily driven by practical determinants linked to electricity demand, access to coal resources, manufacturing employment concentrations, and transmission infrastructure. These economic and operational factors overshadowed racial demographics at the moment of site selection.

Yet, paradoxically, decades following the commissioning of these energy generating units witnessed significant increases in the share of Black residents within counties hosting fossil fuel power plants. The research quantified an average rise of approximately four percentage points in Black population share within 50 to 70 years after the first plant establishment, signaling a complex interplay between initial industrial placement and subsequent demographic evolution.

This demographic trend corresponds temporally with major population realignments in U.S. history, most notably the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to northern industrial cities between 1910 and 1970. This substantial movement into urban and surrounding areas with fossil fuel infrastructure was accompanied by corresponding outflows of White populations to suburban and peripheral counties, reshaping racial compositions and intensifying environmental justice concerns.

The authors suggest that a combination of mechanisms, including economic opportunity, housing segregation, and localized migration patterns influenced by environmental quality, contributed to these demographic shifts. Such local sorting in and around counties with operating power plants underscores a nuanced landscape of environmental and racial justice where mobility patterns rather than initial siting decisions may drive long-term exposure disparities.

This revelation holds profound implications for the formulation of equitable energy and infrastructure policies. Rather than narrowly focusing on preventing discriminatory siting, policymakers must also account for the enduring lifecycle effects of infrastructure investments—including the social and demographic transformations occurring many decades after plants begin operation.

By adopting a lifecycle perspective, urban planners and regulators can better anticipate the social dynamics that accompany industrial infrastructure, allowing for more effective interventions aimed at mitigating disproportionate burdens on vulnerable populations over time. This holistic view advances environmental justice objectives beyond the immediate context, emphasizing sustained equity through the full duration of infrastructure life.

The researchers further emphasize the challenges inherent in studying these patterns at the county level, noting that such spatial units may mask finer-grained demographic variations within urban and suburban neighborhoods. Future analyses deploying more localized data could further elucidate the micro-scale interactions between power plant siting and demographic shifts.

Importantly, this study pioneers a methodological approach integrating socio-economic variables with historical infrastructure data across an extensive temporal horizon. By controlling for influential siting determinants such as coal availability, manufacturing employment, and transportation networks, it disentangles the complex factors shaping spatial racial inequalities linked to energy production.

The findings disrupt simplistic narratives that attribute current environmental injustices solely to biased siting practices, redirecting attention toward the social transformations that unfold across infrastructural lifespans. This insight prompts a reassessment of responsibility and highlights the necessity of longitudinal strategies in both research and policy domains.

Ultimately, this body of work underscores that the social costs and benefits of energy infrastructure are neither static nor confined to their inception. Instead, they evolve in concert with broader societal trends and demographic fluxes that can entrench or alleviate disparities over generations. Recognizing and addressing these dynamic processes will be vital to achieving truly just and sustainable energy futures.

As the global community grapples with climate change and equitable transitions away from fossil fuels, understanding the intricate social lifecycle impacts of past infrastructure decisions offers invaluable lessons. These insights can inform not only environmental justice advocacy but also the design of resilient, inclusive energy systems attuned to the complex realities of demographic evolution.

Subject of Research: The study investigates the long-term social and demographic impacts of fossil fuel power plant siting in the United States, focusing on how post-construction population shifts influence disparities in environmental exposure.

Article Title: The Social Lifecycle Impacts of Power Plant Siting in the Historical United States

News Publication Date: 31-Aug-2025

Web References: http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w34109

References:

- Karen Clay et al., “The Social Lifecycle Impacts of Power Plant Siting in the Historical United States,” NBER Environmental and Energy Policy and the Economy, 2025.