Authorship Inequities in Global Health Research: A Closer Look at Family Medicine Journals

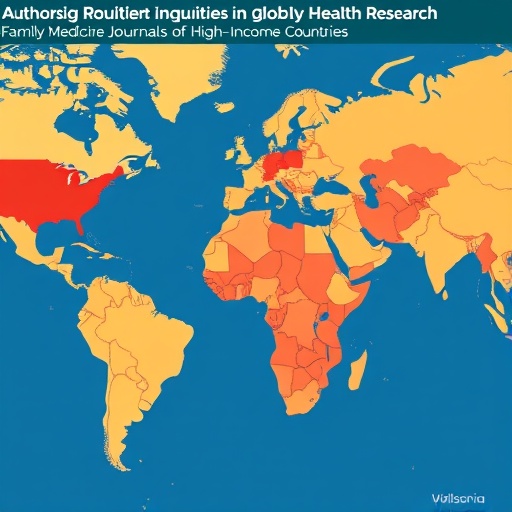

In the ever-evolving landscape of global health research, disparities in authorship and leadership roles remain a pressing concern. A recent study delves into these inequities by examining the dynamics of authorship in research conducted within low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) but published in family medicine journals headquartered in high-income nations. This investigation offers a critical lens on the systemic barriers that impede equitable research representation and leadership from LMIC contexts, particularly in a field as vital as family medicine.

The study, conducted by Dr. Alyssa Vecchio and colleagues from the University of New Mexico and Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School, scrutinizes publications indexed on the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) Global family doctor website. The focus was on journals whose editorial offices reside in high-income countries but which featured research centered on LMICs—categorically low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries. By setting stringent inclusion criteria—studies had to be conducted in LMICs, published in English, and involve human participants—the researchers aimed to draw a clear picture of authorship distribution and its evolution over time.

A substantial dataset was analyzed: out of 1,030 examined articles, 431 met the established criteria for having research conducted in LMICs. This sizeable corpus revealed trends and inequalities that are both illuminating and concerning. Over recent years, there has been a noticeable increase in the publication of family medicine research originating from LMICs, especially from upper-middle-income countries, which accounted for 55.9% of these studies. This reflects a growing recognition of the importance of diverse global contributions in family medicine but simultaneously exposes an uneven distribution favoring relatively better-resourced middle-income countries.

Nevertheless, a critical dimension of the study is the examination of authorship positions, particularly first and senior authorship—roles often synonymous with intellectual leadership and overall project responsibility. The results highlight a persistent imbalance: senior authors affiliated with high-income countries (HICs) dominated 50% of papers focused on low-income countries, compared to 37% and 21% in studies from lower-middle and upper-middle-income countries respectively. This gradient underscores the disproportionate influence HIC-based researchers exert over knowledge production, especially in the most underserved settings.

Such disparities pose significant questions about research autonomy and capacity building in LMICs. The senior author, often the principal investigator or team leader, typically shapes study design, analysis, and interpretations. The dominance of HIC senior authors may inadvertently perpetuate neo-colonial patterns in global health research, whereby high-income institutions dictate research agendas and knowledge dissemination, sometimes marginalizing the contextual insights and priorities of local investigators.

Additionally, the study observes a trend related to citation impact: articles with first and senior authors from high-income countries tend to receive a higher average citation rate than those whose primary authorship originates from lower-middle-income countries. This finding raises complex issues concerning visibility, influence, and academic networks, suggesting that systemic advantages enjoyed by HIC researchers extend beyond authorship into the realm of academic recognition and impact metrics.

The methodology employed in this study is notable for its rigorous approach to classifying countries by income based on World Bank standards and carefully vetting journals through the WONCA platform, which connects family medicine practitioners worldwide. By focusing on journals whose editorial offices are situated in HICs, the researchers isolate the impact of power dynamics embedded within the publication process itself, which remains a critical gatekeeping mechanism in scientific disseminations.

Importantly, the focus on family medicine journals is significant because this specialty addresses comprehensive, community-oriented healthcare—an area profoundly influenced by sociocultural and economic contexts. Ensuring equitable authorship is paramount to fostering research that is not only globally inclusive but also contextually relevant and responsive to the health systems and needs of diverse populations.

The findings resonate with broader calls within the global health community for decolonizing research practices and promoting collaboration models that empower researchers from LMICs. Enhancing authorship equity forms one pillar of such efforts, aimed at dismantling implicit biases, enhancing capacity, and rebalancing knowledge production. Establishing mentorship, infrastructure support, and equitable funding mechanisms are among the strategies essential for shifting these entrenched patterns.

Moreover, the study prompts reflection on the editorial policies and peer-review practices of family medicine journals based in high-income countries. Journals have a critical role in fostering diversity by adopting inclusive authorship guidelines, transparent conflict of interest disclosures, and actively encouraging submissions led by LMIC researchers. Editorial boards themselves need diversification to better reflect global contributors, thereby addressing structural imbalances from within the publication apparatus.

The academic culture surrounding citations and impact metrics also warrants ongoing scrutiny. The observed higher citation rates linked to HIC first and senior authors may reflect inequities in access to academic networks, visibility, and dissemination resources. Developing alternative evaluation metrics that recognize diverse scholarly contributions and promote regional contextualization can mitigate these disparities.

In summary, this study underscores the persistent challenges that researchers based in LMICs face in assuming leadership roles within global health research, particularly within family medicine. It highlights that while output from these regions is increasing, systemic authorship inequities endure, perpetuated by structural, economic, and institutional factors. Recognizing and addressing these barriers is fundamental to advancing global health equity and ensuring that research agendas truly reflect and serve the needs of diverse populations.

This work by Vecchio and colleagues offers a crucial evidence base that policymakers, funding bodies, academic institutions, and journal publishers must heed. Only through concerted, multifaceted efforts can the global health research community move toward a more just and inclusive scholarly ecosystem where leadership and credit are fairly shared, and local expertise is fully valued.

Subject of Research: Authorship inequities in global health research conducted in low- and middle-income countries

Article Title: Authorship Inequity in Global Health Research Conducted in Low- and Middle-Income Countries and Published in High-Income Country Family Medicine Journals

News Publication Date: 27-May-2025

Web References: Not provided

References: Not provided

Image Credits: Not provided

Keywords: Family medicine, Global health, Authorship inequity, Low- and middle-income countries, Academic publishing, Research leadership