In the intricate world of archaeology, deciphering the social fabric woven through ancient ceramic artifacts has long been a pursuit marked by both fascination and frustration. Traditional ceramic analyses often fall short when confronting the subtle nuances that differentiate communities of potters, especially when their productions appear outwardly indistinguishable. A groundbreaking method detailed in a recent study by Ofer Harush, published in Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, is transforming how we understand these material cultures by focusing on the microscopic variations that embed distinctive social signatures into pottery.

Central to this revolutionary framework is the recognition that pottery is not merely utilitarian; it is an embodiment of cultural identity and technical knowledge specific to communities of practice. These communities do not operate in isolation but integrate into unique social networks that shape learning pathways, traditions, and craftsmanship. Each potter absorbs and reproduces these influences, leaving behind a morphometric fingerprint that, when analyzed correctly, reveals the intricacies of social affiliations and learning legacies.

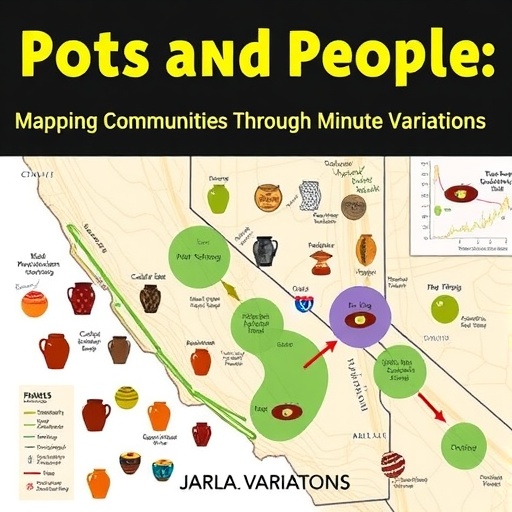

Harush’s approach challenges the conventional archaeological assumption that “pots equal potters” by proposing a refined paradigm: “single type equals potters.” This subtle yet profound shift emphasizes the study of a single ceramic type in minute detail rather than broad assemblages. By honing in on the morphological variability within a narrowly defined category, this methodology preserves the principle that individual artisans leave identifiable marks on their creations, even when overall typology seems uniform.

An illuminating example comes from a comparative ethnographic study of Hindu and Muslim potters in Rajasthan. These two communities produce seemingly identical water jars using the same clay mixtures and manufacturing processes. This produces ceramic profiles indistinguishable under traditional classification, effectively masking community-specific signatures. Yet, through the detailed analysis of subtle morphological variations—imperceptible to the naked eye—the research successfully teased apart the two production traditions, proving that conventional typology can overlook meaningful differences embedded deep within the material.

Ethnoarchaeology plays a pivotal role in bridging the interpretive gaps left by the absence of direct observational data in archaeological contexts. By studying the living potters and their production processes, researchers gain analogical frameworks that illuminate how social behaviors and technological decisions manifest materially. This contextualization is crucial in validating minute variation analysis and discerning the social dynamics behind ceramic production that archaeological excavation alone cannot expose.

However, identifying individual potters within a community remains an elusive challenge, particularly in highly standardized and intensively produced assemblages. The Rajasthan study further reveals that individual variability emerges more clearly when analysis is conducted at smaller scales, such as within village-level production units. This aligns with the understanding that apprentices develop distinct motor skills and individual “ways of doing” that persist amidst overarching cultural paradigms, forming unique stylistic outputs over time.

Supporting this, experimental studies involving ceramic trainees tasked with repetitive production under strict protocols have demonstrated that even with controlled variables, individual styles naturally surface. These findings underscore the potential to trace personal signatures in potter communities and suggest that with refined tools and methodologies, archaeological ceramics might yield insights into individual agency and craftsmanship from millennia past.

The cornerstone of this three-phase analytic approach lies in its commitment to quantitative rigor and objective data handling. It integrates advanced technologies such as 3D scanning and automated classification algorithms to measure and interpret morphological variability beyond subjective visual assessment. By quantifying differences rather than merely categorizing them, this method brings a new level of precision to ceramic studies, ensuring results are statistically robust and replicable.

Nevertheless, the toolset demands significant computational resources and expertise, posing challenges for wider adoption in regions or institutions with limited access to such technologies. To address this, Harush advocates for comprehensive methodological transparency, encouraging researchers to employ cross-validation techniques, replicate analyses through independent datasets, and adhere to predefined significance criteria. Moreover, the promotion of open-access source code and datasets stands to bolster reproducibility and deepen collective confidence in the method’s efficacy.

When applied selectively to homogeneous ceramic types within well-documented collections, the minute variation methodology proves invaluable in uncovering subgroup distinctions, cultural boundaries, and shifts in production that conventional pottery classification misses. This ability to detect subtle social signals within archaeological material culture offers profound new avenues to explore historical communities and their interactions, mobility, and technological transmissions.

Yet it is critical to acknowledge that the approach, while powerful, is not static. Ongoing refinement in typological precision and broader assemblage analysis is essential. Large-scale studies encompassing extensive ceramic corpora from both archaeological sites and contemporary craftsmen promise to enrich the reference datasets needed to identify increasingly nuanced morphometric parameters along ceramic profiles. This iterative process will sharpen the sensitivity of the method, facilitating the detection of ever more subtle variations that serve as proxies for social practice.

The promise of this research paradigm extends beyond academia, potentially reshaping how museums, conservators, and cultural heritage professionals interpret ceramic artifacts. The web of social relations embedded within pots reveals not simply objects of utility but dynamic records of human interaction, knowledge transmission, and identity negotiation. Minute variation analysis renders the invisible visible, spotlighting the quiet signatures of individuals and communities across time.

By melding technological sophistication with ethnoarchaeological insights, this three-phase method offers a renewed lens on ancient material culture. It invites researchers to think beyond typological categories and embrace the complexity inherent in artisanal production. As advancements in 3D imaging and computational methods continue to democratize, the minute variation approach promises to become a standard bearer in archaeological ceramic analysis, fostering richer, more textured narratives of our collective past.

Ultimately, ceramic vessels are not silent relics; they are storytellers encoded with the fingerprints of countless hands guided by tradition, innovation, and individual artistry. This minute variation approach breathes life into archaeological assemblages, transforming static collections into dynamic archives of human expression and cultural continuity. It underscores the essential truth that behind every pot is a person—and behind every pattern, a community eager to tell its story.

Subject of Research: Tracing social and cultural patterns in ceramic production through detailed morphometric analysis to differentiate communities and individual potters.

Article Title: Pots equal people: tracing communities of practice via minute variation approach.

Article References:

Harush, O. Pots equal people: tracing communities of practice via minute variation approach. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1314 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05645-7

Image Credits: AI Generated