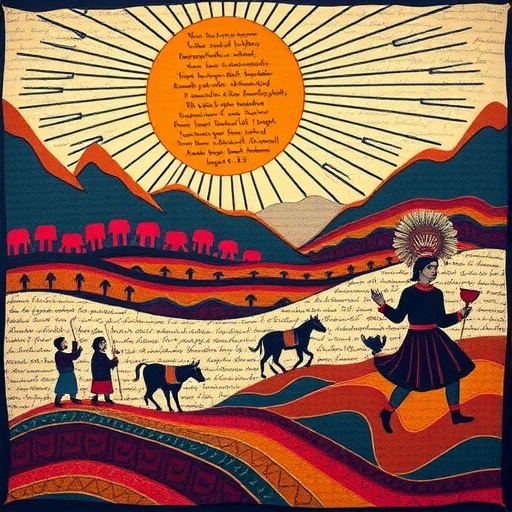

In the Central Andes, a captivating folktale known as Juan Oso offers an unprecedented window into the complexities of oral tradition development, challenging long-held assumptions about cultural transmission. Recent analyses of numerous recorded versions of this tale, gathered across diverse Quechuan-speaking communities, have revealed surprising patterns of variation that defy straightforward explanation. Unlike many folk narratives, Juan Oso’s iterations do not adhere to expected geographical, linguistic, or phylogenetic structures, pointing to a more intricate cultural process at work in shaping oral histories.

Geographical proximity often underpins the diffusion and evolution of folklore, yet the Juan Oso story presents an exception. While some Southern Peruvian versions near the Cuzco region diverge noticeably with unique elements, overall spatial patterns fail to emerge consistently. Intriguingly, even within the same locale, storytellers produce versions that vary dramatically, sometimes reaching an extent of difference as great as any between widely separated locations. This suggests that proximity does not guarantee uniformity or linear cultural transmission, presenting a puzzle for researchers relying on geography as a basis for understanding oral tradition variation.

Beyond geography, linguistic affiliations typically offer a reliable proxy for cultural continuity, especially in orally transmitted formats. Quechuan, a diverse language family with multiple dialects, would thus be expected to influence the storylines or motifs that storytellers adopt. However, rigorous statistical analyses including Redundancy Analyses indicate that the variations in Juan Oso’s narrative bear no clear correlation with the Quechuan speech varieties in which they were recited. Such independence implies that the tale’s developmental history transcends simple linguistic boundaries, and likely reflects a shared narrative framework established prior to the early 16th century when Quechuan dialects were already extensively diversified.

Perhaps most strikingly, an evolutionary approach to the tale’s dissemination—where innovations accumulate through vertical transmission over generations and geographical spaces—finds limited support in the Juan Oso corpus. While some narrative elements cluster geographically and seem to represent shared innovations, such as the adoption of a “magic password,” these constitute rare exceptions rather than the prevailing pattern. This lateral transmission of motifs, possibly influenced by non-Andean stories like Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, hints at a dynamic interplay in the storytelling landscape whereby oral traditions evolve through creative borrowings rather than strict descent.

The absence of clear geographical, linguistic, and phylogenetic structuring in the Juan Oso tradition compels us to reconsider core assumptions in the study of folklore evolution. Despite the relatively large volume of data collected from this underrepresented New World region, the number of documented versions remains small compared to the extensive European folktale archives, limiting statistical power. Nevertheless, qualitative insights drawn from ethnographic literature shed important light on the specific cultural and historical contexts shaping the storytelling practices of Andean communities.

Juan Oso transcends mere narrative to function as a penetrating allegory revealing Indigenous perspectives on colonial and modern power structures. The malevolent priest figure in the story embodies a ruthless embodiment of colonial authority, doubling as a symbol for the wealthy landowning elite with sweeping worldly influence. This duality underscores deep ethnic tensions permeating the Andean social fabric, juxtaposing Indigenous peoples, denoted by the Quechua term runa, against the agentive, often adversarial mestizo colonial society represented by the priest.

The term runa itself carries a nuanced semantic ambiguity, meaning not only “human being” but specifically Indigenous person. In the narrative, this contrasts with the predatory bear and, allegorically, with the mestizo Catholic priest, who are grouped as outside the runa category. This categorization slyly suggests that mestizos and animals alike share traits of cunning and exploitation, reflecting the complex identity negotiations and social boundaries inherent in colonial contact zones. This subtle ethnic commentary echoes through multiple variations of the tale, reaffirming its critical cultural resonance.

Another rich interpretive layer pertains to gender relations and marriage. The abduction of the young woman by the bear, her victimization, and the husband’s oppressive role resonate with Andean women’s lived realities. Ethnographic accounts note how Andean wives sometimes refer to their husbands as ukubus, or bears, highlighting a metaphor for domineering male behavior. Parallel narratives involving predatory animals disguised as men, such as a condor proposing marriage under false pretenses, reinforce themes of deception and the vulnerability of women within marital arrangements.

Remarkably, some Southern Peruvian Juan Oso versions merge with the condor tale, illustrating a fluid narrative hybridization process. This fusion is not incidental but indicative of storyteller agency, deliberately weaving complementary stories to emphasize marriage tensions and dangers. Such intratextual linking illustrates the storytellers’ active role in crafting narratives that speak meaningfully to their socio-political milieu rather than passively transmitting fixed versions. The resultant hybrid reflects adaptive narrative strategies entwined with cultural negotiation.

These entwinements likely extend beyond marriage-related themes. For instance, the “magic password” trope traced to the Ali Baba story reveals cross-cultural narrative borrowing—a striking example of lateral motif transmission within Americas oral traditions. The password’s function reframes the bear as a ‘thief,’ aligning indigenous storyteller creativity with global storytelling motifs. Furthermore, variation in minor plot details, such as roles assigned to birds within the story, exemplifies spontaneous narrative inversions, where, for instance, a hummingbird informs either the bear or the fleeing woman, reflecting the storytellers’ improvisational flexibility.

Such structural transformations and reversals are well-documented in folklore studies, traced to cultural frameworks where storytelling is a living, performative act continually reshaped through social interaction. Levi-Strauss famously emphasized this fluidity, noting how folktales resist stable linearity, instead embodying dynamic cultural symbols subject to contextual reinterpretation. Juan Oso thus exemplifies the broader human tendency to mold oral narratives to local values, tensions, and socio-political realities.

Embracing this complexity, the Juan Oso case study ultimately challenges pale assumptions that cultural variants necessarily adhere to gradual, tree-like evolutionary processes akin to genetic inheritance. Instead, it foregrounds the significance of lateral transmission, hybridization, and storyteller creativity as forces molding oral traditions. The Andean example demands nuanced methodologies integrating quantitative and qualitative tools, recognizing that oral lore is often an arena of active social commentary rather than passive inheritance.

Future research in folklore evolution must increasingly account for such intricacies by integrating ethnographic context with rigorous statistical models. The confluence of Indigenous agency, colonial history, and cultural syncretism evident in Juan Oso’s variations underscores the vital contributions of localized narrative strategies in resisting homogenizing models of cultural evolution. Beyond the Andes, similar patterns may be pervasive but overlooked due to limited interdisciplinary approaches.

Ultimately, Juan Oso offers a cautionary tale for scholars: the evolution of oral traditions cannot be fully understood via neat categories like geography, language family, or phylogeny alone. In narratives laden with embedded social critiques and shaped by historical trauma, the intangible interplay of agency and context shapes storytelling more profoundly than simplistic diffusion models suggest. As digital archives and computational tools expand, capturing this complexity responsibly becomes both an exciting opportunity and an essential imperative for the humanities and social sciences.

The Juan Oso narrative invites us to reconsider what it means for a story to “develop” across generations—not as immutable entities passed down but as vibrant, contested cultural resources continually shaped by communities. Its many versions attest to a storytelling tradition that is alive, innovative, and deeply embedded in the socio-political landscapes of the Quechuan-speaking Andes. By embracing the complexities revealed in this dataset, researchers can advance a richer understanding of how oral literature functions as a mirror and agent of cultural identity in an ever-changing world.

Subject of Research: The development and variation of the Juan Oso oral tradition in Quechuan-speaking regions of the Central Andes.

Article Title: How oral traditions develop: a cautionary tale on cultural evolution from the Quechuan-speaking Andes.

Article References:

Urban, M. How oral traditions develop: a cautionary tale on cultural evolution from the Quechuan-speaking Andes.

Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1604 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05335-4

Image Credits: AI Generated