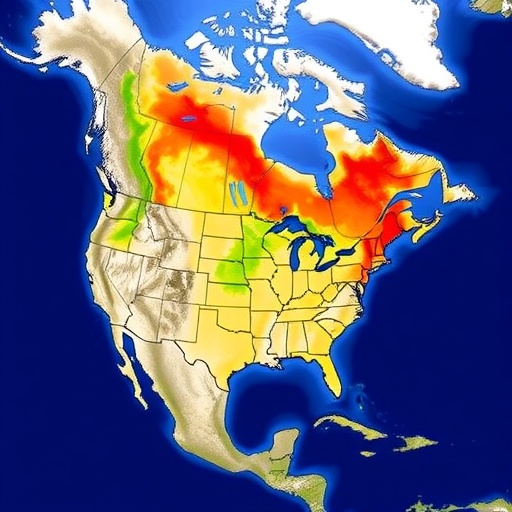

Melting of North American ice sheets at the end of the last ice age has been identified as a far more significant driver of global sea-level rise than previously understood, according to groundbreaking research led by Tulane University scientists. Published in the prestigious journal Nature Geoscience, this study fundamentally challenges longstanding views on glacial retreat dynamics and their climatic consequences. By revisiting deglaciation patterns and their hydrological impacts, scientists are now prompted to reconsider the complex interplay between ice sheet melt, ocean circulation, and climate stability in both past and future scenarios.

For decades, prevailing scientific consensus emphasized Antarctic ice melt as the primary contributor to global sea-level rise during the critical period roughly 8,000 to 9,000 years ago. This study overturns that assumption by presenting compelling evidence that North American ice sheets were the dominant force behind an astonishing increase of approximately 10 meters (30 feet) in global sea levels. Such a revision in the ice melt narrative not only reshapes paleoclimatology but also informs models predicting the fate of modern ice sheets under anthropogenic warming.

Professor Torbjörn Törnqvist, a leading geologist and co-author of the study, notes that this paradigm shift implies a much larger influx of freshwater into the North Atlantic Ocean than previously recognized. This freshwater injection has profound implications for the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a critical driver of global climate regulation. The AMOC, encompassing key currents like the Gulf Stream, is responsible for moderating the climate of Northwest Europe and influencing precipitation patterns across distant regions such as the Amazon basin.

One of the most intriguing outcomes of the study is the indication that, despite this substantial freshwater forcing, the AMOC demonstrated remarkable resilience in the past. Contrasting recent projections warning about the imminent weakness or collapse of the Gulf Stream, these findings suggest complexities in ocean-atmosphere feedback mechanisms remain inadequately resolved. Understanding the conditions that allowed this robustness offers vital insights for anticipating future climate trajectories and potential tipping points within the oceanic conveyor system.

A critical breakthrough underlying this research was the discovery of ancient marsh sediments deep beneath the Mississippi River near New Orleans, found by former Tulane postdoctoral researcher Lael Vetter. These relic sediments, securely dated via radiocarbon techniques, provide an invaluable sea-level record extending back over 10,000 years. Such terrestrial archives are rare and offer unprecedented precision for reconstructing deglaciation timelines, especially when combined with global datasets.

Building on this regional record, former PhD student Udita Mukherjee integrated sea-level data from Europe and Southeast Asia, crafting a comprehensive comparative framework. This global approach was essential in revealing differential rates of sea-level change that demanded an explanation far beyond localized melt scenarios. Only extensive melting of North American ice masses could reconcile these discrepancies, proving the value of incorporating diverse geographic data for paleoclimate reconstructions.

The implications of these findings extend well beyond academic debate. The enhanced understanding of freshwater inputs and their interactions with oceanic currents refines projections of how modern ice sheet melt—especially from Greenland and North America—may disrupt climate patterns. As coastal communities and ecosystems face increasing threats from sea-level rise, insights gleaned from deep-time events become indispensable for crafting adaptive strategies.

Furthermore, this study underscores the remarkable complexity of Earth’s climate system, where multi-regional feedbacks and nonlinear responses often defy simplistic modeling. It calls attention to the necessity of a truly global perspective in climate research, integrating data from diverse locations and disciplines. By broadening investigative scopes beyond North America and Europe to include regions like Southeast Asia, scientists enhance their capacity to detect emergent patterns and causal relationships.

The comprehensive nature of this research was made possible through international collaboration, involving experts from Canadian institutions such as the University of Ottawa and Memorial University, Maynooth University in Ireland, and the University of South Florida. Funding support from the U.S. National Science Foundation enabled acquisition and analysis of high-quality samples and data critical to robust conclusions.

Scientifically, this refined timeline and quantification of ice melt magnitude during the last deglaciation invites revision of climate models used to interpret both past events and future risks. By quantifying freshwater fluxes more accurately, researchers can better simulate their effects on ocean circulation and regional climate anomalies. Such precision is crucial for assessing the thresholds that may trigger abrupt changes in key systems under ongoing global warming.

Overall, the study not only reshapes our understanding of Earth’s climatic recovery from extreme glacial conditions but also highlights the nuanced and interconnected nature of ice sheets, oceans, and atmosphere. As ongoing climate change accelerates, recognizing the lessons from this distant past provides a critical empirical foundation to navigate an uncertain future.

Subject of Research: Sea-level rise dynamics at the end of the last deglaciation and the role of North American ice sheets.

Article Title: Sea-level rise at the end of the last deglaciation dominated by North American ice sheets.

News Publication Date: 9-Oct-2025

Web References: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01806-0

Image Credits: Photo by Torbjörn Törnqvist/Tulane University.

Keywords: Sea level change, Earth sciences, Oceanography, Sea level rise, Ice sheet melt, Climate change, North Atlantic circulation, Gulf Stream, Deglaciation, Paleoclimate, Freshwater influx, Mississippi Delta sediments.