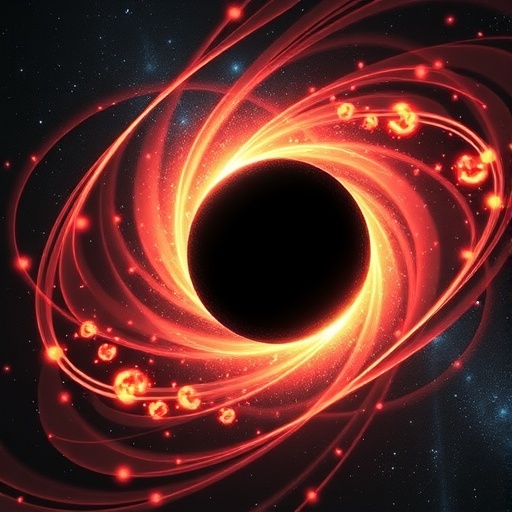

In a groundbreaking theoretical advance, researchers from Oxford University and the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics have outlined a novel method to detect tightly bound supermassive black hole binaries—some of the most enigmatic and powerful objects in the cosmos. While astronomers have confidently observed widely separated pairs of these colossal black holes formed during galactic collisions, the challenge has been to detect those in their closest orbits before their eventual merger. This pioneering study proposes leveraging gravitational lensing effects on starlight to identify these hidden binaries through distinctive, quasi-periodic flashes, offering a promising electromagnetic window into these cosmic cataclysms long before gravitational wave observatories come online.

Supermassive black holes, with masses millions to billions times that of the Sun, reside at the centers of nearly all massive galaxies. When galaxies merge, their central black holes become gravitationally bound, creating a binary system that not only influences the evolution of galaxies but also serves as a formidable source of gravitational waves rippling through spacetime. Until now, observing these pairs in close orbit proved elusive due to their compact separations and the scarcity of direct electromagnetic signatures. However, the new paper published in Physical Review Letters introduces an innovative approach that could revolutionize their detection using existing and imminent wide-field electromagnetic surveys.

At the crux of this discovery lies the remarkable phenomenon of gravitational lensing—whereby massive objects bend and focus light from background sources, acting like natural cosmic telescopes. Unlike single black holes, whose extreme lensing manifests only when a star aligns almost perfectly with the observer’s line of sight, binary black holes produce a far richer pattern. The dual gravitational field creates complex caustic structures—diamond-shaped curves where light magnification can spike dramatically. While idealized models suggest infinite amplification for point-like stellar sources crossing these caustics, real stars finite in size still experience intense, albeit finite, brightening that can flash repeatedly as the binary orbits.

Professor Bence Kocsis of Oxford’s Department of Physics, a leading voice behind this research, emphasizes the profound difference binaries make: “The chance that starlight behind a supermassive black hole is strongly magnified increases substantially for binary systems compared to single black holes. Their combined gravitational fields sweep enormous volumes of space, boosting detection prospects.” This effect creates an exquisite observational signature—a series of recurring light bursts—that could be disentangled from other astrophysical phenomena.

The binary black holes are dynamic entities in motion, orbiting one another and gradually inspiraling as gravitational waves siphon away orbital energy, a process predicted by Einstein’s general relativity. This inspiral modulates the caustic shapes and their sweeping patterns across background star fields, imprinting unique temporal and brightness variations on the flashes observed. Hanxi Wang, a graduate student at Oxford who led the study, explains: “As the black hole duo moves, the caustic structures rotate and evolve. When a bright star crosses these caustics repeatedly, we expect to see quasi-periodic bursts of light whose timing and intensity contain encoded information about the binary’s masses and orbital decay.”

Such a technique offers an extraordinary opportunity. By analyzing these bursts, astronomers could extract fundamental parameters of supermassive black hole binaries, charting their inspiral trajectories well before they merge. This electromagnetic method acts as a complementary probe to upcoming space-based gravitational wave observatories, potentially providing early warnings or continuous tracking of these titanic systems and enabling true multi-messenger astronomy.

The timing of this development is particularly fortuitous. Wide-field optical and near-infrared surveys are on the horizon, led by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. Equipped with high cadence and sensitivity, these instruments are optimized for spotting transient events across large swaths of the sky. The repeating bursts produced by gravitational lensing caustics present an unambiguous hallmark amid the complex zoo of variable stars and active galactic nuclei, making detection plausible in the next several years.

Beyond detection, characterizing tightly bound black hole binaries promises to deepen our understanding of galaxy growth and black hole evolution. These binaries are key agents influencing star formation, gas dynamics, and the architecture of galactic cores through their immense gravitational and energetic outputs. Observing them electromagnetically prior to merger enhances our ability to test predictions of general relativity in the strong-field regime, explore accretion processes around binaries, and reconcile gravitational wave data with electromagnetic counterparts.

Dr. Miguel Zumalacárregui of the Max Planck Institute highlights the profound implications: “Supermassive black holes function as cosmic telescopes, bending and magnifying light in extraordinary ways. Detecting these quasi-periodic lensing flashes unlocks a new modality to study black hole binaries long before they become loud gravitational wave sources. It’s a paradigm shift in how we observe the dark heart of merging galaxies.”

This research underscores the synergy between theoretical astrophysics and cutting-edge observational capabilities, pointing to an era where the invisible choreography of black hole pairs can be unveiled through the twinkling light of distant stars. In this way, humanity’s cosmic gaze is sharpened, revealing the complex gravitational ballet that shapes the universe’s most titanic collisions.

As the astrophysical community eagerly awaits data from next-generation observatories, the prospect of witnessing these gravitationally lensed signals is tantalizingly close. Such observations would not only confirm key aspects of black hole physics and gravitational lensing theory but also usher in a new chapter in multi-messenger astronomy—one where the hidden dynamics of supermassive black hole binaries are illuminated by the very light they bend and magnify.

Subject of Research: Detection of supermassive black hole binaries through gravitational lensing and electromagnetic signatures.

Article Title: Black holes as telescopes: Discovering supermassive binaries through quasi-periodic lensed starlight

News Publication Date: 12-Feb-2026

Web References:

DOI: 10.1103/1sfl-87t4

Image Credits: Hanxi Wang