Nitrogen fertilization leads to emissions of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (N₂O) from agricultural soils, accounting for a significant portion of total greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. It has long been assumed that these N₂O emissions are unavoidable.

Nitrogen fertilization leads to emissions of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (N₂O) from agricultural soils, accounting for a significant portion of total greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. It has long been assumed that these N₂O emissions are unavoidable.

However, an international team of researchers led by NMBU has discovered a method to reduce these emissions. They have identified bacteria that can “consume” nitrous oxide as it forms in the soil, preventing the gas from escaping into the atmosphere. The researchers believe that this method alone has the potential to reduce agricultural nitrous oxide emissions in Europe by one-third.

The N₂O problem

Plants need a lot of nitrogen to grow. A productive agriculture, therefore, requires an abundant supply of nitrogenous fertilizer. This was a bottleneck in agriculture until Fritz Haber pioneered technology for the industrial production of nitrogen fertilizer from atmospheric nitrogen. This technology has contributed to the world’s food production keeping pace with population growth for 120 years.

However, there are microorganisms in the soil that produce the greenhouse gas N₂O, and fertilization stimulates this production.

“This greenhouse gas has an effect that is about 300 times stronger than CO₂, and agriculture accounts for about three quarters of Europe’s N2O emissions,” explains Wilfried Winiwarter, one of the coauthors of the study and a senior researcher in the Pollution Management Research Group of the IIASA Energy, Climate, and Environment Program.

“Also, globally, agriculture is the primary source of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere. Nitrous oxide emissions are primarily regulated by soil bacteria, making reduction efforts challenging due to their elusive nature,” he adds.

Bacteria can do the job

Researchers at NMBU have been conducting basic research for over 20 years on how microorganisms in the soil convert nitrogen. They have, among other things, thoroughly studied what happens when the microbes do not have access to enough oxygen, a condition called hypoxia.

When fertilization occurs (and during rainfall), some parts of the soil become hypoxic. Since the microbes then do not have access to oxygen, they are forced to find other ways to get energy. Many microbes can use nitrate instead of oxygen, and through a process called denitrification, they convert the nitrate into other gases. One of these is nitrous oxide, and in this way, the microorganisms contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

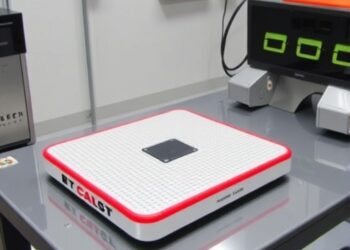

The researchers have made significant discoveries regarding the regulation of this process, and they have developed a unique way to study denitrification. They use, among other things, robotic solutions both in the laboratory and in the field, and have developed a special robot that can make real-time measurements of nitrous oxide emissions from the soil.

The solution to reduce N₂O emissions is to use a special type of bacteria that lacks the ability to produce nitrous oxide but can reduce nitrous oxide to harmless nitrogen gas (N₂).

“If we grow these microbes in organic waste used as fertilizer, we can reduce N₂O emissions. This could mean a solution to the problem of N₂O emissions from agriculture,” says Lars Bakken, lead author of the study and a professor at NMBU.

“But it was not easy to find the right bacterium. It must be able to grow quickly in organic waste, function well in soil, and live long enough to reduce N₂O emissions through an entire growing season. It was also a challenge to go from testing this in the laboratory to trying it out in nature, and to ensure that it actually reduced N₂O emissions in the field,” Bakken adds.

The research team is now working to find more bacteria that consume nitrous oxide and to test these in different types of organic waste used as fertilizers worldwide. The goal is to find a wide range of bacteria that can function in different types of soil and with various fertilizer mixtures.

Adapted from a press release prepared by NMBU.

Reference:

Hiis, E., Vick, S., Molstad, L., Røsdal, K., Jonassen, K., Winiwarter, W., Bakken, L. (2024) Unlocking bacterial potential to reduce farmland N2O emissions Nature DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07464-3

IIASA researcher contact:

Wilfried Winiwarter

Senior Research Scholar

Pollution Management Research Group

Energy, Climate, and Environment Program

winiwart@iiasa.ac.at

Press Officer

Bettina Greenwell

IIASA Press Office

Tel: +43 2236 807 282

greenwell@iiasa.ac.at

About IIASA:

The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) is an international scientific institute that conducts research into the critical issues of global environmental, economic, technological, and social change that we face in the twenty-first century. Our findings provide valuable options to policymakers to shape the future of our changing world. IIASA is independent and funded by prestigious research funding agencies in Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe.

Journal

Nature

Article Title

Unlocking bacterial potential to reduce farmland N2O emissions

Article Publication Date

29-May-2024