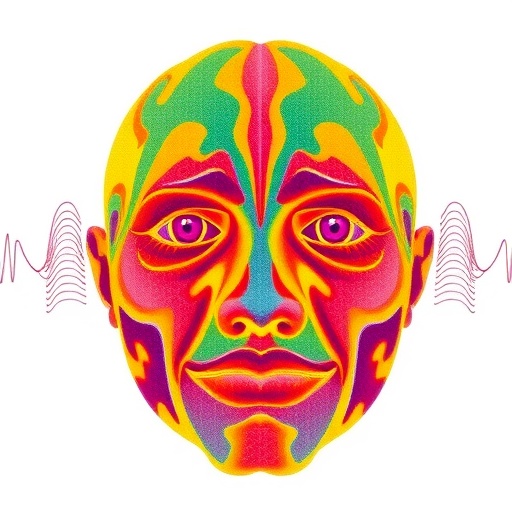

Recent advances in cognitive neuroscience have taken a significant leap forward with the publication of a groundbreaking study uncovering the neural dynamics underpinning spontaneous face perception. In the latest issue of Communications Psychology, a team of researchers led by Robinson, Stuart, and Shatek presents compelling evidence for distinct stages of face processing in the human brain. This revelation not only deepens our understanding of how the brain deciphers one of the most socially critical visual stimuli – the human face – but also challenges longstanding assumptions concerning the fluidity and immediacy of facial recognition mechanisms.

Human faces serve as a vital channel for social communication, providing cues about identity, emotional states, intentions, and even health status. The ability to recognize and interpret faces rapidly and accurately is a cognitive feat finely tuned through evolutionary pressures. Previous research has predominantly focused on controlled, task-driven settings where participants actively engage in face recognition. However, the new findings emphasize the brain’s spontaneous and unprompted engagement with faces, portraying face perception as a multi-stage neural process occurring even without explicit attention or intention.

At the heart of this discovery is a sophisticated neuroimaging approach combining electroencephalography (EEG) with advanced machine learning algorithms to parse the temporal and spatial characteristics of face-related brain activity. By recording neural signals from participants exposed to naturalistic scenes containing faces, the researchers extracted signatures of face perception unfolding over time. Their analysis revealed two separate neural stages: an initial rapid detection phase followed by a more elaborate processing interval. This bifurcation challenges the assumption of a monolithic or unitary face recognition process operating in the brain.

The initial rapid stage, occurring within 100 to 150 milliseconds after face presentation, is characterized by early visual cortical activity localized mainly in the occipital and posterior temporal regions. This phase is believed to serve as a rudimentary feature detector, signaling the presence of face-like patterns in the visual field. Importantly, this detection occurs spontaneously, without the need for focused attention or conscious awareness. The swift nature of this early activation suggests an evolutionary advantage, ensuring that faces are flagged promptly amidst complex visual environments.

Subsequent to detection, a second, temporally distinct stage arises approximately 200 to 300 milliseconds post-stimulus. This phase engages higher-order cortical areas such as the fusiform face area (FFA) and the superior temporal sulcus (STS), regions well-known for their roles in detailed face processing, including identity recognition and the interpretation of facial expressions. Here, neural activity becomes more elaborate, integrating visual information with stored memories and contextual cues. The spontaneous engagement of these areas signifies a deeper perceptual analysis, supporting functions that transcend simple recognition and venture into social cognition realms.

The delineation of these two stages emerged from the researchers’ novel use of representational similarity analysis (RSA), a technique that quantifies the correspondence between neural patterns and model predictions over time. This method allowed the team to track how face perception evolves dynamically within the brain’s architecture. Their findings indicate that initial detection is driven by bottom-up sensory features, while the later processing stage incorporates top-down influences such as expectations, previous experience, and social context. Such an interplay aligns with contemporary frameworks in cognitive neuroscience emphasizing predictive coding and hierarchical processing.

Beyond illuminating the mechanics of face perception, the study carries profound implications for understanding neurodevelopmental conditions like autism spectrum disorder (ASD), where face processing anomalies are prominent. By dissecting the timeline and neural substrates of spontaneous face perception, this research offers a refined map that could guide biomarker discovery and therapeutic interventions. For instance, disruptions in either of the two identified stages may underpin the social perception deficits observed in ASD, thereby targeting specific neural circuits for remediation.

Moreover, the revelation of distinct stages augments artificial intelligence (AI) efforts to replicate human facial recognition. Current deep learning models often process faces in a single-step pipeline, lacking the temporal hierarchy and spontaneous analysis observed in biological systems. Integrating a dual-stage processing framework, inspired by these neuroscientific insights, could enhance the efficiency and accuracy of AI algorithms in fields ranging from security to human-computer interaction.

Methodologically, the study sets new standards in brain imaging research. Its reliance on naturalistic stimuli rather than simplified, artificial images enhances ecological validity, capturing neural responses as they occur in real-world viewing conditions. Furthermore, the integration of EEG with computational modeling provides a robust bridge between observable brain signals and underlying cognitive processes. Such methodological innovations pave the way for future research on spontaneous perception across other domains, such as object recognition, language processing, and emotional evaluation.

An intriguing aspect of the work lies in its exploration of spontaneous, rather than task-evoked, neural responses. Traditional experiments have typically instructed participants to perform explicit face identification or discrimination tasks, which inadvertently activate attention-dependent pathways. In contrast, this study reveals that the brain continuously processes faces embedded in the environment, reflecting an ongoing, automatic social vigilance. This insight reshapes our conceptualization of attention, suggesting a default prioritization of socially salient stimuli at the neural level.

The findings prompt a reevaluation of how face perception contributes to social behavior. Recognizing faces swiftly and without deliberate effort likely serves as a foundational platform for complex social interactions. The brain’s ability to transition from rapid detection to detailed appraisal ensures that individuals can both spot conspecifics in their environment and interpret subtle social signals such as emotional expression or gaze direction. This temporal unfolding supports adaptive responses crucial for cooperation, competition, and communication.

Looking forward, the study’s authors advocate for expanding research to capture how spontaneous face perception operates across different sensory modalities and contexts. For example, integrating auditory cues like voice or emotional tone with visual face processing could provide a multidimensional portrait of social cognition. Additionally, investigating developmental trajectories could clarify how these neural stages mature and whether interventions can enhance face perception abilities.

Importantly, this research also opens avenues for understanding how spontaneous face perception may be altered by mental health conditions beyond autism, such as schizophrenia or social anxiety disorder, where face processing disruptions are documented. By layering temporal and spatial dynamics of neural activity, clinicians might better pinpoint aberrations and tailor treatments accordingly.

At a theoretical level, the study bolsters the view that perception is not a passive reception of sensory inputs but an active, dynamic synthesis involving multiple neural computations unfolding over time. The brain’s capacity to rapidly detect and then scrutinize socially relevant stimuli exemplifies this principle, blending immediacy with complexity.

Finally, as the digital age increasingly blurs human-computer boundaries, understanding spontaneous face perception bears relevance for technology-mediated social interactions. Virtual reality, telepresence, and social media platforms could be designed to leverage or accommodate the brain’s intrinsic processing stages, fostering richer, more naturalistic user experiences.

In sum, Robinson, Stuart, Shatek, and colleagues have charted a nuanced, time-resolved neural map of spontaneous face perception that promises to reshape cognitive neuroscience, clinical practice, artificial intelligence, and social technology development. By exposing the brain’s elegant choreography of detection and detailed processing, this study underscores the sophistication of human social cognition and lays the groundwork for transformative applications spanning health, technology, and society.

Article References:

Robinson, A.K., Stuart, G., Shatek, S.M. et al. Neural correlates reveal separate stages of spontaneous face perception. Commun Psychol 3, 126 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00308-4

Image Credits: AI Generated