Interbrain synchrony, the fascinating phenomenon where neural activities in two or more brains align during social interactions, has increasingly captured the scientific community’s attention. This dynamic alignment, often described as brains being ‘in tune,’ plays a crucial role in enhancing emotional connections, improving communication efficacy, and syncing attention between individuals engaged in joint activities like talking, learning, or playing. The intricacies of this neural dance are particularly vital in the sphere of parent-child relationships, where emotional bonding and effective communication are foundational.

Recent groundbreaking research from the University of Nottingham has revealed a compelling facet of interbrain synchrony: it remains robust across different language contexts within bilingual families. Published in the prominent journal Frontiers in Cognition, this study challenges lingering assumptions about the limitations of bilingual communication, especially between mothers and their young children. Contrary to concerns that using a non-native language might disrupt the delicate neural interplay essential for bonding, the findings indicate that bilingual mothers and their children maintain strong neural synchrony regardless of whether they converse in the mother’s native tongue or her second language.

This research, spearheaded by Dr. Efstratia Papoutselou, offers refreshing insights into how bilingualism might influence the neural foundations of familial interactions. Dr. Papoutselou emphasizes that the neural connection critical to parent-child bonding is preserved “irrespective of whether they play in the mother’s native language or in an acquired second language.” This discovery holds profound implications for multilingual families, dispelling myths that non-native language use inherently impairs emotional closeness and communication quality.

Globally, the prevalence of bilingual and multilingual households is surging, with statistics from the European Union revealing a significant rise from 8% to 15.6% in ‘mixed-language’ homes over less than a decade. The advantages of multilingual upbringing — including cognitive flexibility, enhanced problem-solving, and cultural empathy — are well-acknowledged. Yet, questions have lingered about whether the slower pace and increased cognitive load often associated with speaking a second language might create barriers in high-stakes emotional exchanges like those between parents and children.

Second-language speakers frequently describe a sensation of emotional detachment when using their non-native language, potentially affecting how affection, discipline, and empathy are communicated within the family sphere. This dynamic raised the question: could bilingualism inadvertently impose an emotional distance by altering the neural synchrony that underpins effective bonding? Dr. Papoutselou and her team sought empirical answers to these concerns via a carefully controlled experimental design.

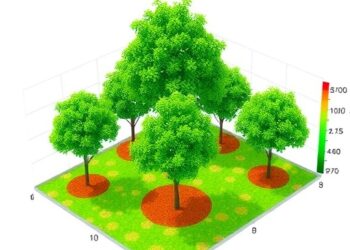

The study enlisted 15 bilingual families residing in the UK, where mothers spoke English as an acquired language at advanced proficiency levels (CEFR levels C1 or C2). The children involved were notably young, ranging from three to four years old—a critical developmental window for language and socio-emotional skills. To capture the neural interplay between mothers and children, researchers employed functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), a non-invasive technique that measures changes in blood oxygenation linked to neural activity. Importantly, both participants wore fNIRS caps simultaneously, allowing for real-time tracking of brain synchrony across multiple regions.

During the experiment, mother-child pairs engaged in different play scenarios in randomized order: interactive play using the mother’s native language, interactive play using English exclusively, and a control condition involving silent, independent play separated by a screen. The researchers’ approach was meticulously naturalistic, permitting observation of neural synchrony during real-life communicative interactions rather than artificial language tasks.

Analysis revealed significant interbrain synchrony in all mother-child pairs, with more pronounced neural alignment during interactive play compared to independent activity. This synchrony was especially intensified in the prefrontal cortex, a brain region integral to executive functions such as decision-making, emotional regulation, and social cognition. In contrast, lower synchrony was observed in the temporo-parietal junction, a hub for attentional and social processing mechanisms. These nuanced findings underscore the complex, region-specific orchestration of brain networks during social engagement.

Crucially, the magnitude of this synchronized brain activity did not differ between the bilingual mother-child pairs’ native language and their second language interactions. This equivalence suggests that despite the additional cognitive demands and perceived emotional detachment sometimes associated with non-native language use, the underlying neural connection facilitating bonding remains intact. The research thus reframes bilingualism not as an obstacle but as an environment where rich, meaningful neural attunement can flourish.

Beyond the immediate implications for family dynamics, these findings advance our broader understanding of how language contexts shape brain function during social interactions. They contribute to a growing body of evidence illustrating the brain’s remarkable plasticity and adaptability in accommodating multiple languages without sacrificing the fundamental neural processes that enable human connection. This adaptability is vital in an increasingly multilingual and multicultural world.

Professor Douglas Hartley, the study’s senior author, eloquently summarizes this paradigm shift: “Bilingualism is sometimes seen as a challenge but can give real advantages in life. Our research shows that growing up with more than one language can also support healthy communication and learning.” His statement highlights that bilingual environments not only nurture cognitive benefits but also preserve the neural substrates essential for emotional and social development.

This study also invites further exploration into the mechanisms by which bilingualism interacts with other dimensions of cognitive and emotional development. Future research might examine whether similar neural synchrony patterns are evident in other types of social dyads or extend across varied age groups and language combinations. Moreover, longitudinal studies could illuminate how these neural synchrony patterns evolve as children mature within bilingual environments.

In the practical realm, these findings offer reassurance to families navigating multilingual upbringing. They affirm that switching between native and acquired languages within parent-child interactions need not compromise the emotional depth or neural attunement underlying these relationships. For educators, clinicians, and policymakers, the study provides a scientific basis to support language diversity at home and in early childhood programs while emphasizing the resilience of the human brain’s social wiring.

In essence, the study unearths a foundational truth about human connection: language, whether first or second, does not constrain the brain’s ability to create bonds. Instead, it enriches the tapestry of interaction, proving that bilingual brains can indeed move in harmony, transcending linguistic boundaries to maintain core social and emotional ties. This revelation reshapes our understanding of language’s role in social cognition and paves the way for a more inclusive appreciation of diverse family realities in the modern world.

Subject of Research: People

Article Title: The Impact of Language Context on Inter-Brain Synchrony in Bilingual Families

News Publication Date: 18-Feb-2026

Web References: 10.3389/fcogn.2025.1695132

References: Frontiers in Cognition

Keywords: Interbrain synchrony, Neural synchrony, Bilingualism, Parent-child bonding, fNIRS, Brain plasticity, Multilingual families, Social cognition, Prefrontal cortex, Language acquisition