In the quest to better understand the socio-economic landscape of Sub-Saharan Africa, a novel study has emerged, meticulously conceptualizing the notion of “hardship areas” across this diverse region. The research, spearheaded by Auma, Karing’u, and Harriss along with their colleagues, offers a comprehensive scoping review that dissects the multi-dimensional facets of hardship, transcending simple economic deprivation to encompass a spectrum of social and environmental factors. This study is not only timely but also groundbreaking, addressing a critical gap in regional development discourse and policy formulation. It offers a fresh lens through which researchers, policymakers, and international development agencies can view economic and health inequities, potentially reshaping intervention strategies for one of the world’s most complex and dynamic regions.

The research trajectory highlights the challenges inherent in defining “hardship areas” within Sub-Saharan Africa, a region noted for its heterogeneity in terms of geography, political stability, cultural diversity, and economic development. Traditionally, metrics for hardship have been narrowly focused on income, neglecting the intricate interplay of health disparities, environmental vulnerabilities, infrastructure deficits, and social exclusion. This study broadens the conceptual framework by incorporating these crucial elements, enabling a more nuanced identification and understanding of hardship that is sensitive to the local realities of affected populations.

Central to this study is the intricate methodology applied in assembling and analyzing data from a vast array of sources spanning environmental, economic, and social domains. The authors engaged in a scoping review methodology, which is particularly adept at synthesizing evidence from heterogeneous sources and disciplines. This approach allowed them to map the existing literature comprehensively, categorize various definitions and indices of hardship, and illuminate areas where data gaps and conceptual ambiguities persist. Such methodological rigor underpins the reliability and relevance of their conceptual model.

Importantly, the study does not merely stop at identifying hardship areas but delves into the causal pathways and feedback mechanisms that sustain and exacerbate deprivation. For instance, it explores how environmental degradation—such as soil erosion, water scarcity, and climate change-induced phenomena—intersects with limited access to healthcare, education, and economic opportunities. This systems-focused analysis underscores the complexity of poverty and vulnerability, advocating for integrated, multi-sectoral approaches rather than siloed interventions.

One striking revelation from the research is the role of governance and institutional capacity in either mitigating or magnifying hardship. The authors reveal that regions plagued by political instability, weak public administration, and inconsistent policy enforcement are disproportionately affected by persistent hardship. This insight challenges simplistic economic explanations and points toward governance reforms and enhanced institutional frameworks as pivotal levers for regional development and equity.

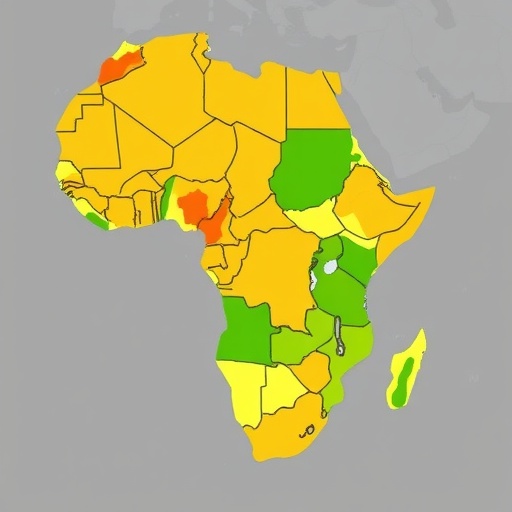

Another pivotal aspect tackled in the article is the spatial heterogeneity of hardship within nations and across borders. By mapping hardship to specific geographic locales—rural hinterlands, peri-urban slums, and conflict zones—the authors provide a layered understanding of how geography mediates access to resources and vulnerability levels. Such spatial analysis is invaluable for targeting resources efficiently, advocating for precision in development aid and policy targeting that moves beyond national averages and generalizations.

Delving deeper into the health dimension, the study sheds light on how endemic diseases, malnutrition, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure exacerbate hardship. By coupling health metrics with economic and social indicators, the authors argue for a health equity perspective that recognizes the bidirectional nature of health and hardship. Chronic illness not only results from poverty but also perpetuates it by limiting productivity and draining household resources, creating vicious cycles that demand concerted intervention.

The environmental factors discussed in the study emphasize the growing urgency of climate change and its disproportionate impact on Sub-Saharan Africa’s hardship areas. The researchers discuss the concept of “climate vulnerability hotspots,” where worsening weather patterns intensify food insecurity, displace populations, and strain fragile infrastructures. This intersection of environmental stress and socioeconomic hardship signals a need for adaptive strategies that integrate resilience-building with poverty alleviation.

Furthermore, this conceptualization of hardship areas has profound implications for data collection and monitoring. The study underscores the need for improved, standardized metrics that capture the multifaceted nature of hardship, including qualitative dimensions often overlooked in large scale datasets. Advances in geospatial technologies, remote sensing, and participatory data collection are highlighted as promising tools for enhancing the granularity and timeliness of hardship assessments.

One of the most compelling contributions of the research is its potential to reshape international development priorities. By offering a robust, multidimensional framework, the study equips global agencies and local governments with a blueprint for designing more effective, context-sensitive programs that align closely with the lived realities of communities. This can potentially transform aid allocation from broad-brush poverty reduction schemes to finely tuned interventions that address underlying determinants holistically.

The authors also address the social fabric of communities in hardship areas, emphasizing the roles of social capital, cultural resilience, and local knowledge systems in mediating the impacts of adversity. This perspective is crucial in avoiding reductionist views of impoverished areas as mere deficits, instead recognizing the agency and adaptive capacities of populations. Embedding these social dimensions into hardship conceptualization paves the way for empowerment-oriented development strategies.

Critically, the study contributes to academic debates on the definition of poverty and development in the African context. It challenges universally applied models and calls for culturally informed frameworks that resonate with the unique historical, social, and environmental contexts of Sub-Saharan African societies. Such theoretical advancements hold promise for enriching multidisciplinary discourse and fostering more just and equitable knowledge production.

The policy relevance of this conceptual review cannot be overstated. As Sub-Saharan Africa continues to grapple with rapid demographic shifts, urbanization, and climatic upheavals, nuanced understandings of hardship will be essential for crafting responsive, sustainable policies. The authors’ work lays the intellectual groundwork for such systemic thinking, situating hardship at the crossroads of health equity, environmental sustainability, governance, and socioeconomic development.

In conclusion, this landmark scoping review presented by Auma and colleagues redefines how hardship is understood and operationalized within Sub-Saharan Africa. Its methodological sophistication, expansive scope, and forward-looking implications provide a clarion call to researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to rethink approaches to regional equity and development. By embracing complexity and multidimensionality, this study promises to catalyze more effective, equitable interventions that truly address the root causes of hardship.

As the world converges on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that emphasize no one left behind, the findings from this research amplify the necessity of localized, data-driven, and integrated strategies. Future research inspired by this study will likely delve further into intervention efficacy, community engagement models, and longitudinal impacts, pushing the frontier on how hardship and resilience are intertwined in one of the globe’s most pivotal regions.

Understanding hardship areas through this novel conceptual lens offers a new paradigm in the African development discourse—one that prioritizes depth over breadth, integration over fragmentation, and local realities over generalized assumptions. This research stands as a beacon for multi-disciplinary inquiry, policy ingenuity, and global solidarity in pursuit of equitable health and socio-economic outcomes.

Subject of Research: Conceptualizing and defining hardship areas in Sub-Saharan Africa through a multidimensional scoping review encompassing social, economic, health, environmental, and governance factors.

Article Title: Conceptualising hardship areas in Sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review.

Article References:

Auma, C.M.N., Karing’u, P., Harriss, E. et al. Conceptualising hardship areas in Sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Int J Equity Health 24, 326 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-025-02694-x

Image Credits: AI Generated