A groundbreaking genomic study involving over 1,200 individuals from across South Africa offers unprecedented insight into the complex tapestry of ancestry shaped by colonial expansion, indigenous populations, and the Indian Ocean slave trade. Published in the prestigious journal The American Journal of Human Genetics, this research unravels how European colonizers, Indigenous Khoe-San peoples, and enslaved populations from Africa and Asia collectively contributed to the genetic landscape that defines modern South Africans today. By employing cutting-edge genomic sequencing and advanced analytical methodologies, the study sheds light on strong sex-biased admixture patterns that are intricately linked to historical movements and social dynamics during the colonial era.

Researchers collected DNA samples from diverse communities spanning the Western and Northern Cape Provinces, extending from the bustling urban center of Cape Town to indigenous Nama and ≠Khomani San communities in the northern reaches of South Africa. The strategic choice of sampling locations aimed to capture the chronological and geographical gradients of genetic admixture stemming from European colonial influence and the Indian Ocean slave trade. By leveraging genome-wide data, the investigators reconstructed ancestral contributions with high resolution, enabling them to trace not only the origins but also the sex-specific patterns of genetic inheritance.

A central revelation of the study is the pronounced male bias in European ancestry juxtaposed with a corresponding female bias among the indigenous Khoe-San lineages. This finding aligns with historical narratives documenting predominantly male European colonists settling in South Africa, often engaging in unions—sometimes consensual, often forced—with local indigenous women. This sex-biased admixture is detectable through differential patterns on the sex chromosomes: Y chromosomes predominantly signal European male lineage contributions, while mitochondrial DNA and X chromosomes reflect a preponderance of Khoe-San female ancestry. Such insights underscore how genetic data can illuminate facets of colonial social structure and interaction that historical documentation may overlook or obscure.

The gene flow from enslaved individuals originating from equatorial Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia emerges as a complex layer interwoven into South Africa’s genetic fabric. Unlike the European and Khoe-San ancestries, these Asian and African lineages do not exhibit significant sex bias, indicating differing social or demographic dynamics during their integration. The study’s nuanced examination of these communities highlights the vast geographic scope of the Indian Ocean slave trade, extending beyond Africa and influencing genetic patterns far inland.

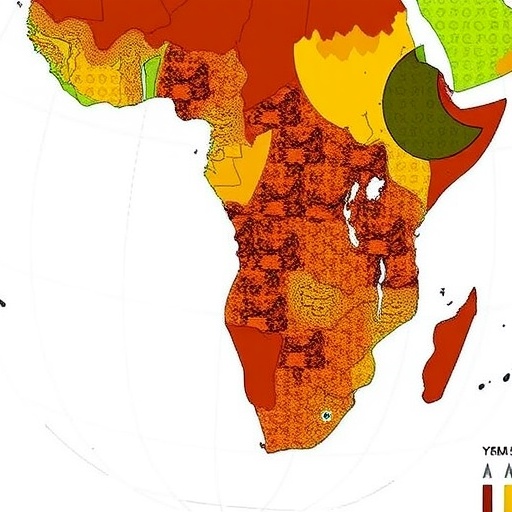

Mapping the geographic dispersal of these ancestral contributions reveals a gradient of genetic influence radiating outward from Cape Town, the colonial epicenter. European and Asian ancestry proportions diminish progressively in communities situated farther from the city, suggesting a clear temporal and spatial expansion of colonial and slave trade impacts. This observation is consistent with historical records chronicling the establishment of Cape Town as a strategic trading post by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1652, and the gradual movement of peoples away from the coast into increasingly remote regions over the subsequent centuries.

In particular, genomic estimates situate key admixture events within the last 7 to 8 generations—roughly 210 to 240 years ago—for Indigenous groups such as the Nama and ≠Khomani San. The research also identifies a striking presence of Asian Y chromosome lineages, notably comprising 15% of the paternal lineages in the Nama population, yet notably absent in the ≠Khomani San. This finding suggests historical migration routes wherein some men of Asian origin either escaped slavery or were freed and migrated extensively northward from Cape Town, integrating into indigenous groups and establishing lasting cultural and genetic legacies.

From a methodological perspective, the research leverages comparative analyses of sex chromosomes (X and Y) alongside autosomal chromosomes, allowing for the detection of sex-biased admixture patterns. The approach benefits from publicly available global genetic datasets providing reference panels against which the South African genomes were compared. This integrative framework enhances the ability to date admixture events, ascertain source populations, and delineate sex-specific ancestry contributions—tools that are critical in disentangling complex demographic histories.

Anthropologist Brenna Henn, the study’s senior author, remarks on the transformative power of genetics to fill in gaps left by sparse historical records. While documents list the names of enslaved and colonizing individuals, the genetic approach can track their reproductive legacy and survival, piecing together a clearer picture of how populations intermixed. Co-author Austin Reynolds emphasizes that the genetic patterns documented are more aligned with the colonial integration observed in Latin America, involving significant incorporation of Indigenous peoples, in contrast to regions such as the United States, where Indigenous incorporation was limited.

The study’s findings carry profound implications for understanding the sociohistorical context of South Africa’s “Colored” communities, a designation rooted in the Apartheid era, though encompassing a complex array of ancestries today. By clarifying the genetic contributions and sex-biased admixture processes in these populations, the research advances both historical understanding and contemporary identity discourses. It also paves the way for future finer-scale analyses targeting the specific origins within Asia and equatorial Africa that contributed to the enslaved populations destined for South Africa.

Notably, the team expresses interest in expanding their genomic analyses to trace specific Y chromosome lineages, potentially linking them with surnames or familial histories. This future research avenue opens possibilities for connecting genetic patterns with personal identities and oral histories, deepening the integration of genomics, anthropology, and social history. Such multidisciplinary avenues highlight how modern genomic tools can revolutionize the study of human migration, colonial impact, and cultural survival.

This research was made possible through funding from prestigious organizations including the South African Medical Research Council, the South African National Research Foundation, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Their support enabled the assembly of extensive genomic datasets and the deployment of complex computational analyses vital for unraveling the nuanced admixture dynamics of South Africa’s population history.

As genomic technologies continue to advance, studies like this one underscore the immense potential to unearth hidden histories embedded within our DNA. The work provides a model for applying genomics to decolonize narratives of human history by revealing the intimate biological consequences of colonialism, migration, and resilience.

Subject of Research: People

Article Title: The Indian Ocean Slave Trade and Colonial Expansion Resulted in Strong Sex-Biased Admixture in South Africa

News Publication Date: 23-Sep-2025

Web References:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2025.08.012

http://www.cell.com/ajhg

References:

Reynolds et al., “The Indian Ocean slave trade and colonial expansion resulted in strong sex-biased admixture in South Africa,” The American Journal of Human Genetics, 2025.

Image Credits: Brenna Henn

Keywords: Human population, Human evolution, Human origins, Indigenous peoples, Demography