A groundbreaking study conducted by a research team from Tel Aviv University offers fresh insights into a captivating aspect of human history: the involvement of children in creating prehistoric cave paintings. For decades, archaeologists have pondered the reasons behind the presence of young children, often seen as very young as two years old, in the depths of ancient caves, some of which are known for hazardous entryways and low oxygen levels. This new research proposes a compelling hypothesis that goes beyond the traditional views regarding children’s roles in early societies. Instead of viewing these excursions as mere educational experiences, the researchers suggest that children were perceived as mediators between the physical world and spiritual realms.

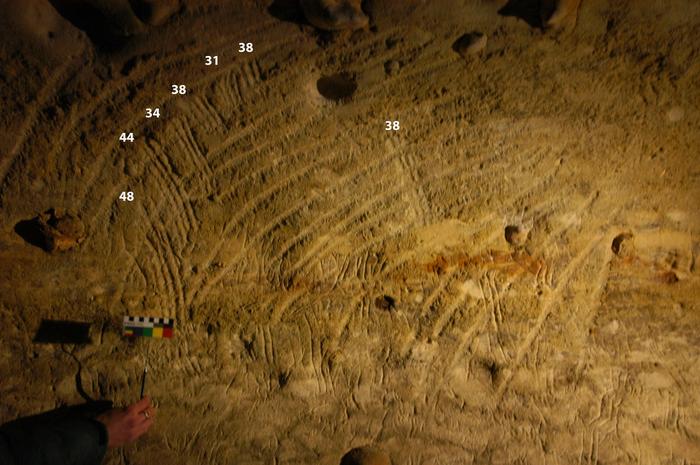

The existence of children’s handprints and finger paintings in many caves across Europe, particularly in regions such as France and Spain, where over 400 caves are identified with prehistoric art, has raised significant questions about their purpose and importance in these subterranean environments. In the light of the new findings, it becomes clear that these artworks do not merely represent a form of learning but instead reflect a deeper cultural and spiritual significance attributed to children’s participation. The researchers emphasize that these figures were thought to possess unique qualities, granting them the ability to communicate with entities from beyond the tangible world.

As part of this investigation, Dr. Ella Assaf, Dr. Yafit Kedar, and Professor Ran Barkai critically evaluated existing hypotheses. Historically, theories surrounding children in cave art primarily revolved around educational objectives, suggesting that their presence was intended to instill knowledge of community traditions and customs. This perspective, however, failed to account for the potential sociocultural roles that children might have played as integral participants in ancient rituals. As such, this study enriches our comprehension of prehistoric societies by illustrating how children’s existence was interwoven within the fabric of communal practices that reached toward the supernatural.

Dr. Assaf articulates that the incredible variety of cave art discovered, some executed between 40,000 and 12,000 years ago, contains unequivocal evidence of children actively engaging in the depiction of art forms that represent their society, identity, and beliefs. This perspective hints that these young individuals were not merely passive observers, but rather active contributors shaping the cultural narratives of their time. Establishing child involvement within these contexts significantly alters our understanding of prehistoric rituals and the relationships that existed between human societies and their beliefs.

In exploring the depths of these great caves, the new research proposes that children were considered more than mere apprentices learning about their heritage. Researchers reveal that children were likely seen as possessing a distinct set of cognitive traits that allowed them to navigate between the mundane and the extraordinary realms. This unique perspective positions them as essential communicators—a link drawn between spiritual entities that predated written history. It suggests that children, instead of being hindered by the inherent dangers of cave exploration, were embraced as valuable participants in the spiritual and communal dimensions of early human life.

As these researchers continue their work, they draw upon existing studies focusing on indigenous societies worldwide. Anthropological insights inform their hypothesis that children in these cultures are often revered as “active agents.” Evidence of this notion emerges in contemporary societies, where children exemplify a deeper understanding of familial and cultural connections, reinforcing the argument that prehistoric children echoed similar roles in ancient civilizations. Such explorations can lead to significant revelations into prehistoric cosmologies, facilitating a broader dialogue about the intricate nuances of early human relationships with their environment.

A notable highlight of the findings includes the researchers’ emphasis on children acting as cultural conduits. Just as practices in various communities employ children in rituals, so too might the practices of prehistoric people have served to foster enduring ties between human beings and the natural world. This ideological shift in thinking can open new avenues for studying the interplay between human societal evolution, cultural expression, and the intrinsic communication patterns that emerge within both children and adults alike.

In addition to the continuing dialogue around child participation, Prof. Barkai contributes insight by explaining the role of caves as spiritual gateways. These underground environments were perceived as thresholds to the underworld. Drumming, singing, and rituals often took on transformative meanings, wherein entrances to these caves served to build relationships with otherworldly spirits. Children were believed to occupy a liminal space in this exploratory venture—straddling two realms, that of the living and the spectral—and thereby were uniquely suited to engage in profound communication with entities in mythological constructs.

Taking these findings into account, it is apparent that this study is not only pertinent in understanding the significance of cave art but also serves as a testament to the cultural fabric of ancient societies. Young children possessed unique access to both worlds, granting them the power to express and articulate desires, messages, and information sought from spiritual entities. The suggestion that children were more than bystanders in these artistic expressions unveils a layer of complexity in social interactions that further our understanding of community structures within prehistoric life.

Ultimately, the researchers advocate for a reevaluation of how we interpret the significance of children’s artistic contributions to cave sites. By strategically combining perspectives from anthropology, archaeology, and sociology, this study pushes the boundaries of understanding our collective past. It encourages further exploration into children’s pivotal role as conduits of cultural significance and as communicators of sacred traditions, emphasizing the idea that our understanding of prehistoric societies is profoundly enriched by reflecting on the contributions of their most innocent members.

This groundbreaking work not only affords us a renewed appreciation for the complex interplay between children and cultural production but also reshapes our understanding of humanity’s earliest artistic expressions. Researchers underscore the importance of examining child involvement through an interdisciplinary lens, enriching the historical dialogue regarding the intricate tapestry of human existence. By unraveling these connections, we are encouraged to engage more deeply with the historic narrative—ultimately granting a voice to those who once roamed the ancient halls of the past.

Subject of Research: The role of children in prehistoric cave art

Article Title: New Study Suggests: This Is Why Children Took Part in Creating Prehistoric Cave Art

News Publication Date: October 2023

Web References: N/A

References: N/A

Image Credits: Dr. Van Gelder

Keywords: Prehistoric art, cave paintings, children, spirituality, archaeology, cultural anthropology, ancient societies, communication, indigenous cultures, liminality, rituals, cognitive development.