In a groundbreaking study published in Nature, researchers have unveiled an intricate and place-based assessment of biodiversity intactness across sub-Saharan Africa, shedding new light on the differential contributions of various land uses to both the loss and preservation of biodiversity. This comprehensive evaluation integrates land use patterns with biodiversity indicators to capture not only the current state of ecological health but also the spatial nuances governing species survival within one of the world’s most biologically diverse regions.

Central to the study’s findings is the overwhelming role of unprotected, largely untransformed lands across sub-Saharan Africa. These areas, covering approximately 80% of the region, harbor an estimated 84% of the remaining Biodiversity Intactness Index (BII), a critical metric measuring the relative abundance and diversity of native species in a landscape. Intriguingly, these vast expanses are also the epicenters of widespread biodiversity loss, accounting for 68% of total BII reductions. This dual role underscores a paradoxical reality: while these lands serve as refuge for biodiversity, they are simultaneously vulnerable to degradation, emphasizing the urgent necessity for sustainable management practices that balance human activity with conservation imperatives.

Protected areas, by contrast, exert an outsized influence relative to their spatial footprint. Though constituting a mere 6% of the sub-Saharan land surface, strictly protected lands contribute about 7% to the remaining BII and are responsible for only 1% of BII loss. This disproportionate contribution highlights the critical role of protected reserves in mitigating biodiversity decline and preserving ecological integrity. However, their limited extent alone cannot compensate for the broader patterns of habitat transformation occurring elsewhere, particularly in agricultural zones.

Agricultural croplands present a complex challenge, covering 14% of the region and contributing 9% of the remaining BII yet driving as much as 29% of the total BII loss. The study delineates croplands as a significant vector of biodiversity decline, reflecting the widespread conversion of natural habitats into cultivated fields. This transformation often disrupts native species assemblages, diminishes ecosystem functions, and facilitates a cascade of ecological consequences that extend beyond the immediate footprint of farmland.

Less abundant land-use types such as settlements, tree croplands, and timber plantations each occupy less than 1% of the landscape and contribute minimally—less than 1%—to both remaining and lost biodiversity intactness. Though small in area, these land uses represent emerging fronts of pressure that warrant close monitoring given their potential to intensify with expanding human populations and shifting economic activities.

Disaggregating these patterns at the biome level reveals further intricacies. Near-natural, unprotected lands dominate remaining BII contributions across forests, savannas, and arid zones, with rangelands playing a similarly pivotal role in biomes such as thickets, grasslands, and the biodiversity-rich fynbos. Protected areas emerge as particularly significant in desert and fynbos biomes, contributing 41% and 23% respectively to remaining biodiversity—a reflection of the strategic conservation efforts in these ecologically sensitive regions.

In contrast, croplands exert prominent negative impacts in grassy biomes such as grasslands, Acacia savannas, and humid savannas. Here, land-use intensity further refines impacts: less intensive croplands predominate in savanna areas, while more intensive agricultural practices, often concentrated in South African grasslands and fynbos regions, correlate with heightened biodiversity loss. These nuanced gradients affirm the necessity of tailoring land management strategies to biome-specific conditions and land-use intensities to optimize biodiversity outcomes.

Rangelands hold a unique distinction as primary drivers of biodiversity loss in the thicket biome. This biome-specific degradation implicates the interplay of grazing pressures with underlying ecological dynamics, offering insights into how traditional land uses can, under certain intensities, become unsustainable and diminish native species integrity.

Forests uniquely demonstrate substantial losses from degradation of near-natural lands, alongside deforestation for conversion to rangelands and croplands. This pattern is emblematic of the broader global narrative where tropical forests remain hotspots of biodiversity loss due to anthropogenic pressures and habitat fragmentation, which alter complex ecological networks and lead to cascading species declines.

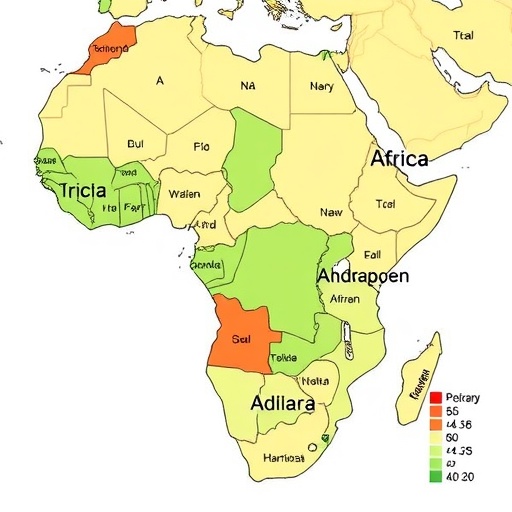

Examining these patterns at national scales reveals variability between biodiversity intactness and the extent of land transformation. Countries exhibiting higher proportions of transformed land tend to possess lower BII scores, aligning with expectations about habitat conversion pressures. However, significant outliers, such as Burundi, challenge this general trend: despite relatively moderate land transformation, Burundi ranks as having one of the lowest BII values. This discrepancy points toward differences in land-use intensity, species vulnerability, and conservation effectiveness between countries.

The cross-country variation also highlights the importance of considering not merely the spatial extent of transformation but its qualitative aspects. Variations in agricultural intensity, protection enforcement, and species adaptive capacity collectively shape a nation’s biodiversity intactness. Such complexity necessitates integrated approaches that couple land-use planning with social, economic, and ecological factors.

Together, these findings paint a nuanced picture of biodiversity intactness across sub-Saharan Africa. They emphasize the critical importance of unprotected, near-natural landscapes for maintaining regional biodiversity, while clarifying that protected areas alone cannot fully offset the extensive transformation occurring elsewhere. Comprehensive conservation strategies thus require balancing protection, sustainable land use, and restoration, especially in cropland-dominated and intensifying agricultural regions.

The study’s data-driven approach leverages the BII as a practical and quantifiable indication of ecosystem health, enabling policymakers and conservationists to prioritize interventions that align with both spatial and categorical risks to biodiversity. Given the rapid land-use changes in sub-Saharan Africa driven by population growth and economic development, this place-based assessment provides timely insights for forging pathways toward reconciling human needs with conservation goals.

In scale and scope, these results underscore the urgent global imperative to harmonize biodiversity conservation with land-use planning. As natural habitats face mounting pressures, capturing spatial heterogeneity in biodiversity loss and persistence through integrative metrics like BII will be indispensable for designing resilient landscapes that sustain both ecological functions and human well-being over the long term.

Subject of Research: Biodiversity intactness assessment in sub-Saharan Africa and its relationship with land use and transformation.

Article Title: A place-based assessment of biodiversity intactness in sub-Saharan Africa.

Article References:

Clements, H.S., Biggs, R., De Vos, A. et al. A place-based assessment of biodiversity intactness in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09781-7