In a groundbreaking discovery that reshapes our understanding of early human migration, researchers from Griffith University have unearthed stone tools on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi dating back over 1.04 million years. This revelation provides irrefutable evidence that early hominins undertook formidable deep-sea voyages much earlier than previously believed, reaching Wallacea—a complex archipelago separating Asia and Australia—during the Early Pleistocene. The site of this remarkable find, Calio, situated in southern Sulawesi, offers unprecedented insights into the capabilities, adaptability, and dispersal routes of our ancient ancestors during a pivotal epoch often overshadowed by later migrations.

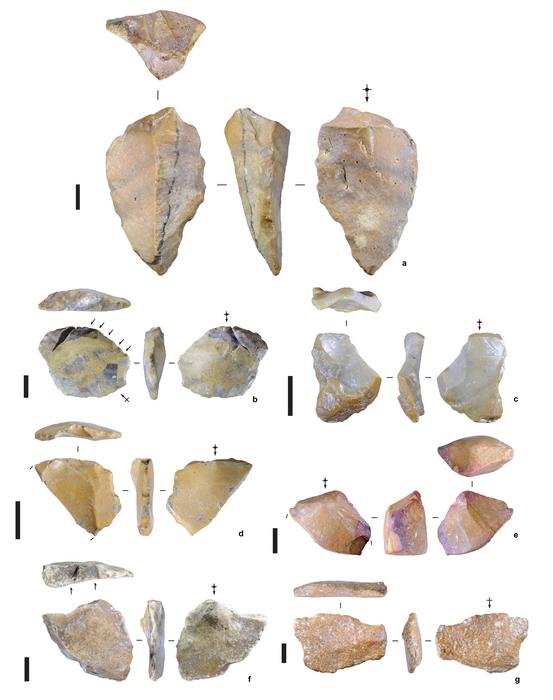

Led by Professor Adam Brumm of the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution and Budianto Hakim from Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), the international research team excavated seven finely crafted stone artefacts from sandstone deposits embedded within a modern agricultural field. These artefacts, composed primarily of small, sharp flakes struck from larger pebbles, indicate a sophisticated level of tool manufacture and use, consistent with early hominin behavior. The precise location—once a river channel in the Ice Age landscape—would have offered a rich ecological niche for tool-related activities such as hunting and butchery. This environment emphasizes not only the technological capabilities of these early populations but also their strategic settlement choices to exploit available resources.

Confirming the extraordinary antiquity of these artefacts required state-of-the-art dating techniques. The research team employed palaeomagnetic analysis on the sandstone layers containing the tools, which involves studying the earth’s historic magnetic field reversals recorded in rock formations, allowing for precise chronological constraints. Complementing this, direct uranium-series dating was applied to associated pig fossils uncovered in the same stratigraphic context. Together, these methodologies have convincingly established a minimum age of 1.04 million years, pushing back previous estimates of hominin occupation in this region by tens of thousands of years. Such a timeline drastically alters our comprehension of the early peopling of Southeast Asia and the complexities of hominin island colonization.

This discovery challenges long-held assumptions about the so-called Wallace Line, a major biogeographical boundary dividing Asian and Australasian fauna. It has traditionally been considered a formidable barrier to terrestrial species due to the deep sea trenches separating islands, and the newly uncovered evidence of hominin presence well to the east of this divide suggests that early humans possessed maritime skills far more advanced than assumed. The ability to cross these substantial water barriers implies early hominins either constructed rudimentary watercraft or demonstrated impressive swimming abilities, raising compelling questions about the cognitive and cultural sophistication of populations living over a million years ago.

Moreover, the Calio site evidence complements previous findings by Professor Brumm’s team on Flores Island, where stone tools dating to at least 1.02 million years ago have been recovered. Flores had earlier made headlines for the discovery of Homo floresiensis, a small-bodied hominin species popularly dubbed the ‘hobbit’ for its diminutive stature. The hypothesis that Homo erectus inhabitants initially reached Flores and later underwent island dwarfism under selective pressure over hundreds of thousands of years remains an enigma. Sulawesi, over twelve times larger than Flores, now represents a critical puzzle piece in this evolutionary narrative, raising questions about whether isolated populations on larger islands experienced similar or divergent evolutionary trajectories.

Sulawesi’s vast size and ecological richness make it a unique ‘mini-continent’ in this prehistoric landscape. If hominins occupied Sulawesi continuously for a million years, their evolutionary path might have diverged substantially from that of their smaller-island counterparts. The absence of hominin fossils at Calio poses a challenge, leaving their exact species identity unresolved. Nonetheless, the sophisticated nature of the stone tools attests to advanced cognitive abilities and adaptability, opening avenues for future paleoanthropological investigations to locate skeletal remains that can clarify which hominins once roamed this island.

The broader implications of this research resonate beyond Sulawesi. Adjacent regions, such as the Philippine island of Luzon, have yielded hominin evidence dating to approximately 700,000 years ago, underscoring a widespread and early dispersal of hominins throughout Southeast Asia. This expanding archaeological record urges a re-evaluation of the timing, routes, and technological innovations that enabled early humans to traverse and settle ecologically diverse and geologically complex archipelagos during the Early Pleistocene. Understanding these migration patterns provides critical context for later Homo sapiens dispersals, as well as insights into how environmental challenges shaped human evolution.

Professor Brumm emphasizes the significance of these findings in reconstructing hominin movement across Wallacea, a transitional zone distinguished not only by its fauna but also by its cultural and biological history. The stone tools from Calio add a crucial data point to the intricate mosaic of early human occupation and technological expression. As the earliest direct evidence of tool-making on Sulawesi, this discovery reframes the prehistoric narrative of human innovation and adaptation in island ecosystems and marine-crossing capabilities.

The Calio artefacts evoke profound questions about the lives, skills, and social organization of the tool-makers who lived there over a million years ago. The meticulous flake production implies not only manual dexterity but also conceptual understanding of lithic technology, demonstrating early hominins’ mastery over their environment. These insights contribute significantly to debates on the cognitive evolution of archaic humans and their capacity to overcome ecological barriers that once seemed insurmountable.

Looking ahead, the research team plans ongoing excavations and regional surveys, aspiring to uncover hominin fossils imperative for taxonomic identification and to refine the chronology of occupation. Such discoveries will shed light on the evolutionary processes acting upon island hominin populations and provide comparative data across Wallacea and beyond. The fusion of archaeological, geological, and palaeontological evidence promises to unveil a richer and more nuanced panorama of Early Pleistocene life in Southeast Asia.

In sum, the discovery at Calio revolutionizes our perspective on early human migration and technological ingenuity. It confirms that hominins ventured across vast maritime landscapes far earlier than assumed, inhabited ecologically varied islands, and engaged in complex behaviors previously unattributed to populations of this antiquity. This advance heralds a new chapter in human evolutionary studies, illuminating the depths of our species’ exploratory courage and adaptive resilience across the prehistoric world.

Subject of Research: Early hominin migration and tool use on the island of Sulawesi during the Early Pleistocene.

Article Title: Hominins on Sulawesi during the Early Pleistocene

Web References:

https://www.eurekalert.org/multimedia/1085131

Image Credits: Credit: M.W. Moore/University of New England

Keywords: Early Pleistocene, hominin migration, Sulawesi, stone tools, Wallacea, Homo erectus, Homo floresiensis, palaeomagnetic dating, deep-sea crossing, island colonization, human evolution, prehistoric archaeology