A groundbreaking genomic study of ancient human remains from the Neolithic Shimao city site in China provides unprecedented insight into prehistoric social structures, migration patterns, and kinship practices during a transformative period in East Asian prehistory. Published in Nature in 2025 by Chen et al., this research leverages an extensive, high-resolution dataset from well-preserved settlements in Shaanxi and Shanxi provinces to uncover the complex genetic and social dynamics underlying the emergence of agro-pastoral societies in the region.

The investigation reveals that the inhabitants of Shimao, situated within the Ordos Loop, predominantly descended from a singular ancestral lineage that shows remarkable genetic continuity from the Middle to Late Neolithic. This finding substantiates earlier archaeological hypotheses suggesting that Shimao city emerged as a political center founded by agro-pastoralist elites originating from the Loess Plateau and Ordos region. The study highlights how this locale served as a crucial genetic and cultural corridor linking farming-associated groups with those practicing herding, effectively delineating Shimao’s large settlements from contemporaneous communities in the Central Plain.

Intriguingly, the genetic data underscore the enduring presence of an inland northern East Asian ancestry linked to the nomadic Yumin populations of the Inner Mongolian steppe—a distinctive genetic component that persists both before and during the Shimao occupation. This persistence suggests a pattern of sustained interaction marked by periodic genetic inflows without disrupting the dominant regional Shimao gene pool. Such findings illuminate long-term coexistence and reciprocal influence between pastoral nomads and Yangshao and Shimao cultural groups, reflecting a gradual subsistence shift toward integrated agro-pastoral strategies.

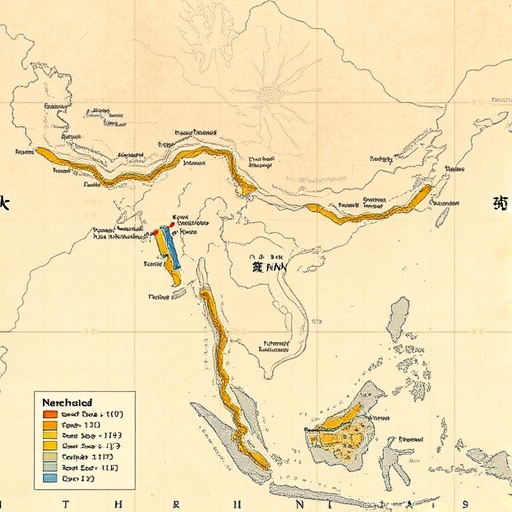

Beyond northern influences, the study also detects a broader genetic input from southern mainland ancestries, notably the Xitoucun culture, as well as coastal indigenous populations represented by Taiwan-Hanben or Ami groups. This ancestral signal, stretching across vast distances from Fujian or Taiwan to Shaanxi and Shanxi, provides genetic corroboration for the archaeological record documenting the northward spread of rice farming and extensive population interactions during this era. However, the precise routes of this southern genetic diffusion—whether direct from coastal or mainland populations or indirectly via the Yangzi River’s Longshan culture—remain open questions pending further sampling.

One of the most striking revelations lies in the remarkable genetic continuity observed within the Shimao population over a millennium, absent notable admixture with other culturally related but genetically distinct groups on the western Eurasian steppe, in Northern and Central Asia, or the eastern coastal Shandong region. This disconnect, despite evidence of artifact imports such as anthropomorphic stone carvings and jade tools from these distant regions, strongly suggests that these material goods were likely acquired through trade rather than population mixing. This disconnect delineates a unique interplay between expansive exchange networks and distinct genetic boundaries.

Comparative genomic analysis between Shimao and contemporaneous settlements like Taosi and Zhoujiazhuang reveals close shared ancestry stemming from pre-Shimao populations in the northern Ordos plain. This finding nuances archaeological models of inter-community relations by substantiating a complex interface marked by trade and occasional conflict. Furthermore, the identification of Yangshao culture-related groups as direct ancestors of these later Shimao and Taosi populations clarifies the origins of political and cultural complexity in this pivotal East Asian cradle of civilization.

Perhaps the most transformative aspect of this study lies in its detailed reconstruction of Shimao’s social organization through kinship analysis. By sequencing DNA from a wide range of burials across different social strata—from high-level elites to commoners and sacrificial victims—the researchers exposed a predominantly patrilineal social structure. Male- and female-specific sacrificial customs also emerged, suggesting ritualized gender roles embedded within a rigid class hierarchy but with notable flexibility as evidenced by elite females occupying high-status positions.

The genomic data enabled the reconstruction of multi-generational pedigrees spanning both elite and common burials, a rare achievement in East Asian archaeological genetics. Unlike comparable pedigrees extensively documented in West and Central Eurasia, these genealogies reflect a large, genetically diverse population with limited close-kin mating, supporting a sizable effective population over centuries. This demographic stability speaks to sustained community coherence and the management of social alliances via ethno-cultural kinship rather than small-scale inbreeding.

Spatial analysis further revealed limited kinship ties or identity-by-descent (IBD) blocks between distinct Shimao cultural communities and between them and geographically distant Taosi cultural settlements. Such genetic stratification implies constrained movement and marriage patterns shaped by cultural or geographical boundaries, underscoring how early social identities were maintained and reinforced via reproductive behaviors.

Remarkably, no direct familial links were found between Shimao elites and the individuals sacrificed in funerary contexts, indicating strong social boundaries surrounding mating and status. Nevertheless, sporadic kinship between elites and lower-status individuals indicates some permeability, raising intriguing questions about social negotiation and mobility within this hierarchical society. The pattern suggests that funerary rituals and sacrifices were tightly regulated practices administered by elites, likely reinforcing political and symbolic power structures.

The study also nuances our understanding of gender and power in ancient Shimao. Though predominantly patrilineal, high-status female individuals demonstrate that gender was not an absolute constraint on social advancement. This insight challenges earlier assumptions of strictly male-dominated leadership and hints at complex gender dynamics within Neolithic power centers in East Asia.

Overall, this exhaustive genomic investigation marks a breakthrough in elucidating how early complex societies in northern China organized themselves socially, managed kin networks, and engaged in dynamic interactions with both local and distant populations. By contextualizing burial practices, artifact distributions, and genetic lineages, the authors illuminate intricate patterns of wealth inheritance, class differentiation, and ritual behaviors that shaped Shimao’s rise as a regional power.

This pioneering research underscores the enormous potential of ancient DNA to unravel the social fabric of prehistoric civilizations, offering a high-definition lens into the lives, identities, and interactions of people who lived thousands of years ago in a critical zone of human cultural evolution. The integration of genetics with archaeology and anthropology provides a compelling model for resolving enduring questions about migration, identity, and social complexity in other ancient societies worldwide.

As this study opens new avenues for understanding Neolithic kinship and social organization, it simultaneously highlights the need for broader sampling across East Asia to discern finer patterns of genetic flow and cultural exchange. Such efforts will further refine our grasp of the complex web of ancestry and interaction that underpinned the emergence of early states and polities in this region and beyond, deepening our appreciation of humanity’s shared past.

Subject of Research:

Ancient DNA analysis of Neolithic populations in Shimao city, Shaanxi and Shanxi provinces, revealing kinship practices, population history, and social organization.

Article Title:

Ancient DNA from Shimao city records kinship practices in Neolithic China.

Article References:

Chen, Z., Gardner, J.D., Sun, Z. et al. Ancient DNA from Shimao city records kinship practices in Neolithic China. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09799-x

Image Credits:

AI Generated