In Antarctica is a small lake, called Deep Lake, that is so salty it remains ice-free all year round despite temperatures as low as -20 °C in winter. Archaea, a unique type of single-celled microorganism, thrive in this bitterly cold environment.

Credit: Joshua N Hamm

In Antarctica is a small lake, called Deep Lake, that is so salty it remains ice-free all year round despite temperatures as low as -20 °C in winter. Archaea, a unique type of single-celled microorganism, thrive in this bitterly cold environment.

University of Technology Sydney (UTS) microbiologists Dr Yan Liao and Associate Professor Iain Duggin, from the Australian Institute of Microbiology and Infection, have been studying how these simple, ancient life forms grow and survive.

“Archaea is one of three lineages of life, alongside Bacteria and Eukarya (organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus, including plants and animals). They are widespread and play a crucial role in supporting Earth’s ecosystems,” said Dr Liao.

A new study published in Nature Communications, led by Dr Liao and Dr Joshua Hamm from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, shows for the first time some of these archaea behave like parasitic predators that rapidly kill their hosts.

“They are less studied and understood than the other lineages. However, archaea provide clues about the evolution of life on Earth, as well as how life might exist on other planets. Their unique biochemistry also holds promising applications in biotechnology and bioremediation.

“They have been found thriving in very acidic boiling hot springs, deep-sea hydrothermal vents at temperatures well over 100 degrees Celsius, in hypersaline waters like the Dead Sea, as well as in Antarctica,” Dr Liao said.

The archaea used in the study were collected from the cold and hypersaline Deep Lake in Antarctica by Professor Ricardo Cavicchioli, a senior author from UNSW Sydney, who initially led this project. Dr Liao and Associate Professor Duggin have also travelled to Australian pink salt lakes to collect archaea.

Within the archaea, there is a group called DPANN archaea that are much smaller than other archaea, with very small genomes and limited metabolic capabilities. The study reveals they depend on host microbes, particularly other archaea, to survive.

“This is the first time such aggressive behaviour has been observed in archaea. In many ways, the activity is similar to some viruses. It leads us to re-evaluate their ecological role in the Antarctic environment,” said Dr Hamm.

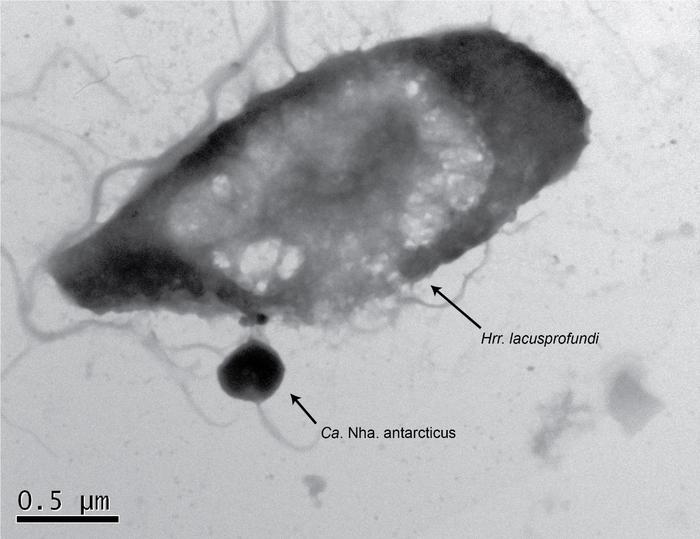

Very few DPANN archaea have been cultivated in the lab, and Dr Liao and colleagues developed new techniques, including unique sample staining, live fluorescence microscopy, and electron microscopy, to visualise the internal parts of the host cells and track interactions between DPANN archaea and their hosts.

Dr Liao stained the host, an archaeon called Halorubrum lacusprofundi, and the parasitic DPANN archaeon Candidatus Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus, with non-cytotoxic dyes that glow with different colours when exposed to laser light.

“This allowed us to observe the organisms together over extended periods and identify the cells by colour. We saw DPANN parasites attach, and then appear to move into the host cell, leading to the host cell’s lysis or bursting open,” she said.

Associate Professor Duggin said predators are important players in ecosystems because when they kill their hosts, they not only feed themselves but also make the remains of the host cells available for other organisms to feed on.

“This allows other microbes to grow and prevents the host organism from hoarding nutrients. The DPANN archaea we investigated appear to play a much more significant role in ecosystems than realised. A parasitic or infection-like lifestyle of these archaea may be common.”

The research was an international collaborative effort involving UTS, the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, UNSW Sydney, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, and the University of Oxford.

Dr Liao said her future research aims to explore archaea for biomedical and biotechnological applications. While no archaea have been found to cause disease, they could still impact wellbeing. Archaea are also responsible for livestock methane emissions, so a greater knowledge of archaeal lifestyles could be useful to combat climate change.

Journal

Nature Communications

Method of Research

Imaging analysis

Subject of Research

Cells

Article Title

The parasitic lifestyle of an archaeal symbiont

Article Publication Date

31-Jul-2024

COI Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.