In recent years, the entertainment industry has witnessed a surge in casting choices that prioritize racial diversity in unprecedented ways. Notably, the casting of Black actors in historically White roles—such as Cleopatra—has sparked a complex and often contentious debate regarding representation, authenticity, and power dynamics in media. This discourse, articulated in the groundbreaking study “Beyond colourblind casting: historical revisionism and Afrocentric blackwashing of Cleopatra in contemporary media” by Saeed, Li, Wu, and colleagues (2025), dismantles the prevailing notion that colourblind casting is an unequivocal path toward inclusivity. Instead, it exposes the structural shortcomings and colonial undercurrents that render colourblind approaches problematic, if not outright harmful, to genuine Black representation.

At its core, colourblind casting promises the appealing ideal of casting actors regardless of race to foster inclusivity. However, scholars argue that this framework is fundamentally flawed because it presumes that race can be abstracted away in a society where racial meanings are deeply entrenched within cultural and social institutions. Anderson’s seminal critique from 2006 emphasized that the very terminology of “colourblindness” is misleading: it suggests an impossible neutrality in a racially stratified world, ignoring how visual racial markers carry potent socio-political significance. This is critically pertinent in media, where representation is not merely an aesthetic choice but a site of cultural semiotics reflecting power structures.

The media’s problematic handling of Afro-American representation is evident when measured against Stuart Hall’s foundational framework for Black cultural identity. Hall, a towering figure in cultural studies, delineated three pillars vital for authentic Black representation: the Black experience, a distinctive cultural repertoire, and a counter-narrative that challenges dominant ideologies. Instead of embedding these pillars into storytelling, many productions opt for superficial gestures—such as casting Black actors in iconic historically White roles—which ostensibly reflect diversity but skirt meaningful engagement with Black cultural realities. This has led to what some critics call “blackwashing,” a phenomenon where Blackness is reduced to a malleable, interchangeable aesthetic easily inserted into narratives without addressing underlying systemic marginalization of Black voices.

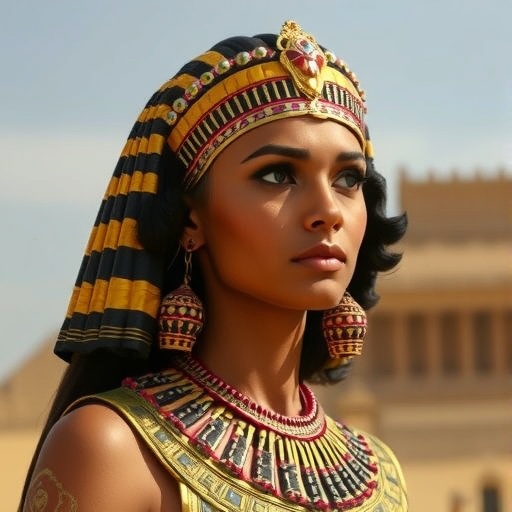

The 2023 adaptation of Queen Cleopatra exemplifies this tension vividly. Cleopatra, a figure of Macedonian Greek descent from the Ptolemaic dynasty, becomes a controversial emblem in this discourse due to the choice of Afrocentric casting. While the casting choice appears to challenge Eurocentric canons by centering Black identity, it simultaneously elides Cleopatra’s specific historical and ethnic context. This practice, rather than honoring Black cultural complexity, arguably perpetuates a colonial framework by commodifying Blackness: Black actors become symbolic tokens deployed to diversify stories while the foundational narratives remain untouched and Eurocentric in essence.

August Wilson’s incisive critique adds an invaluable layer to understanding this paradox. He warned that colourblindness serves as a colonial mechanism that reinvents history, elides Black presence, and maims spiritual cultural products. Wilson’s analogy that colourblind casting is a superficial bandage masking the deep wounds of racial exclusion remains prescient. His analysis illuminates how this practice functions as cultural mimicry—a rehearsal of Black identity stripped of its historical roots and recreated to fit a White gaze. The paradox deepens when Black actors portray historically White figures—Founding Fathers, for example—without the narratives addressing these figures’ entanglements with slavery or colonial oppressions, thus sidestepping uncomfortable histories rather than confronting them.

The problematic embedding of Black actors into White-centric narratives also manifests exploitative dimensions. Colourblind casting commodifies Black identities similarly to colonial extractivism, where Black performers’ labor and cultural capital are mined to project an image of progressiveness without relinquishing creative or institutional control. In this regard, blackwashing imposes a considerable burden on Black artists, expecting them to infuse White-scripted characters with cultural authenticity that the source material lacks. This dynamic resembles a neo-colonial extraction of Black cultural labor—where creative agency remains circumscribed by the dominant paradigm.

Moreover, this commodification has implications far beyond aesthetics. It traps Black performers and audiences within a framework that invalidates their lived experiences, as they are asked to embody characters and histories that have actively excluded or oppressed them. It becomes a cycle of cultural assimilation rather than celebration, where the very symbolism of inclusion camouflages systemic inequities entrenched in casting, narrative sovereignty, and industry power hierarchies.

To truly transcend these limitations, the media industry must embark on a radical reimagining of representation—one that refuses to settle for colourblind casting as an endpoint. Instead, it must prioritize storytelling that centers Black identities on their own terms, interrogates structural inequities, and consciously dismantles colonial legacies embedded within its narratives. This goes beyond tokenistic diversity to embrace equity-driven frameworks where creative control is shared, and Black cultural complexity is neither simplified nor erased.

Failures to grasp these nuances mean that colourblind casting remains a superficial remedy with limited efficacy. It fails to disrupt the architecture of systemic racism because it does not address the deeper socio-historical contexts that shape stories and identities. Existing literature by Day (2021) and Warner (2015) underlines the necessity of confronting institutional bias as an essential step toward authentic racial representation in media—steps that colourblind casting alone cannot fulfill.

Furthermore, a more truthful engagement with Black history in media would require addressing the paradoxes inherent in revising historical narratives. Casting Black actors as founding figures or Ptolemaic rulers could be a form of symbolic reclamation, yet without acknowledging the complicities and contradictions surrounding these histories, such approaches appear to prioritize visual diversity over truth. This also calls attention to the need for intersectional historical literacy in media that can responsibly represent the diasporic odyssey of African Americans alongside global histories.

The scholarly conversation around casting practices reminds us that representation is never neutral. It is inextricably linked to power, history, and identity. Incorporating Black actors into predominantly White roles without deeper structural critique effectively reenacts colonial hierarchies through cultural means, maintaining White hegemony’s status quo under a veneer of progressive change.

Additionally, the entertainment industry’s reliance on blackwashing highlights a broader capitalist logic, where market-driven incentives capitalize on Black cultural aesthetics without committing to systemic transformation. This aligns with critical race theory’s emphasis on how economic structures perpetuate racial inequalities even within seemingly inclusive practices.

In conclusion, the evolution of media casting must move beyond surface-level inclusivity toward transformative equity. This requires consciously rejecting colourblindness’s colonial logics, centering Black experiences authentically, and ensuring collaborative creative agency. Only then can media fulfill its potential as a space for genuine cultural dialogue rather than merely a site for symbolic diversity that masks enduring racial hierarchies.

Article References:

Saeed, A.J., Li, M., Wu, Q. et al. Beyond colourblind casting: historical revisionism and Afrocentric blackwashing of Cleopatra in contemporary media. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1561 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05889-3