Between approximately 55,000 and 42,000 years ago, Europe was a vast and dynamic landscape undergoing one of its most profound evolutionary and cultural shifts. During this pivotal epoch, the Neanderthals, an iconic archaic human species well-adapted to the continent’s environment, were gradually replaced by anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens, who were migrating out of Africa in successive waves. This transitional period has remained the subject of intense archaeological and anthropological scrutiny, particularly regarding the complex interactions between these human groups and the emergence of new cultural expressions. Central to this debate is the Châtelperronian culture, a distinct prehistoric industry located in what is now France and northern Spain, occupying a critical position at the edge of the Paleolithic timeline and raising compelling questions about cultural exchange, innovation, and identity.

Recent excavations have been undertaken at La Roche-à-Pierrot in Saint-Césaire, France, a site of exceptional archaeological significance. Conducted by the laboratory De la Préhistoire à l’actuel: culture, environnement et anthropologie, which is a collaboration between CNRS, the French Ministry of Culture, and the University of Bordeaux, these excavations have uncovered remarkable evidence illuminating the cultural practices of the Châtelperronian people. Most notably, the team unearthed numerous pierced shells alongside an array of mineral pigments that can be definitively attributed to this period. This discovery is groundbreaking because it designates La Roche-à-Pierrot as an authentic workshop where such jewellery was manufactured—an assertion supported by the careful analysis of wear marks and the presence of both perforated and unpierced shells.

The scientific analyses went beyond simple inventory, revealing that the materials were sourced from distinctly distant regions. The shells were traced back to the Atlantic coastline, which was then approximately 100 kilometers from the site, while pigments originated from territories more than 40 kilometers away. This geographical breadth strongly implies the existence of complex exchange systems or significant territorial mobility, practices that underscore a sophisticated social network within these prehistoric communities. Such findings prompt a reconsideration of Neanderthal behavioral complexity, often underestimated, and hint at possible interactions, cultural borrowings, and shared symbolic systems between Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens during this transformative period.

Adding to the intrigue is the repertoire of associated artifacts found at the site, including characteristic Neanderthal stone tools and faunal remains from large mammals such as bison and horses. This assemblage paints a multifaceted picture of human subsistence, tool production, and environmental exploitation strategies in this era. It suggests a cultural landscape where hunting, crafting, and symbolic behavior coexisted, reflecting adaptive versatility and cultural dynamism. More than a mere relic, La Roche-à-Pierrot serves as a window into the everyday lives and social frameworks that shaped human evolution in the Upper Paleolithic.

Until now, the occurrence of early Upper Paleolithic shell bead workshops was primarily documented in Eastern or Central Europe, making these discoveries at La Roche-à-Pierrot the earliest known instance for Western Europe. The significance of these shell beads transcends decorative use; they provide compelling evidence of symbolic thought, social identity, and possibly group differentiation among prehistoric humans. Historically, the explosion of symbolic materials—jewellery, pigments, and artistic expressions—has been attributed chiefly to Homo sapiens. Yet, the presence of such materials in a Châtelperronian context raises the possibility that Neanderthals either independently developed or assimilated symbolic behaviors, thereby challenging long-held anthropological paradigms.

Crucially, these findings revive the debate surrounding the identity of the Châtelperronian artisans. Were they Neanderthals who had adopted new cultural elements through contact and exchange? Or were they an early wave of modern humans whose presence has been archaeologically masked until now? The data from La Roche-à-Pierrot tip the scales toward a scenario where either the Châtelperronian people were influenced by incoming Homo sapiens or were indeed part of a previously unrecognized early Homo sapiens migration into Western Europe. This revelation could recalibrate our understanding of human dispersals, interactions, and the diffusion of cultural innovations in the Late Pleistocene.

The stratigraphy and site formation processes at Saint-Césaire offer an enduring research venue as they document a nearly 30,000-year continuum of human occupation. The sequential layering at this site captures the ebb and flow of multiple human populations and cultures interacting across millennia. Since excavations began in the mid-1970s, the site has yielded invaluable insights. However, it is the integration of newly applied excavation methods and advanced analytical techniques—such as microtomography, pigment analysis, and refined archaeological stratigraphy—that have precipitated fresh perspectives and more nuanced interpretations of the material record.

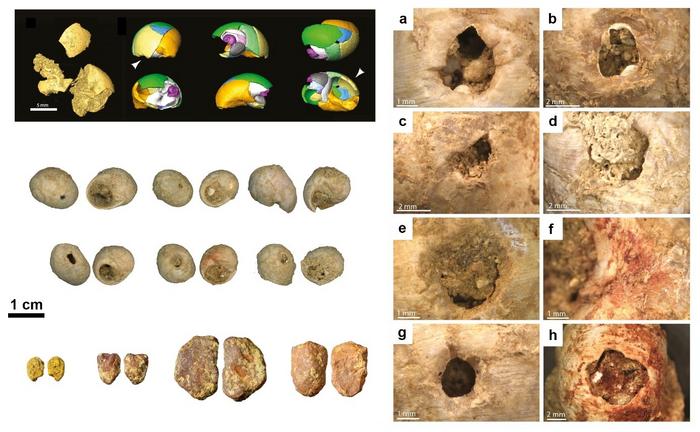

From a technical standpoint, the microtomographic post-processing and virtual reconstructions of Littorina obtusata shells—key materials for ornament production—reveal intricate perforations formed primarily by mechanical pressure. These microscale modifications, accompanied by pigment staining in red and yellow hues, testify to deliberate and skillful manipulation. Such microscopic precision implicates a technological sophistication and intentional symbolic use, rather than purely utilitarian exploitation. These details emphasize not only the craftsmanship of the artisans but also their engagement with symbolic modalities that communicated group identity and social cohesion.

The implications of long-distance acquisition networks also merit attention in reconstructing prehistoric social landscapes. The movement of raw materials over tens of kilometers implies established routes and exchanges that transcend mere survival needs, indicating cognitive and social complexities akin to modern human societies. Whether these networks were maintained exclusively by Châtelperronian populations or also integrated Homo sapiens groups remains an open question, but their existence enriches discussions on territoriality, mobility, and social boundaries during this critical juncture in human history.

Furthermore, the pigments discovered alongside the shells open avenues for exploring the role of color and symbolism in prehistoric societies. The application of red and yellow pigments, both widely recognized in archaeological contexts as indicators of symbolic or ritual practice, aligns with broader patterns of adornment and body decoration. Such practices are often linked to social differentiation, status signaling, or spiritual beliefs, adding a profound cultural dimension to the technological findings. This suggests that symbolic cognition and social complexity were potentially shared or exchanged across different hominin species during the Upper Paleolithic epoch.

The discoveries at La Roche-à-Pierrot contribute significantly to the nuanced understanding of the variability and diversity of Paleolithic cultures during the transition from Neanderthal to modern human dominion. They foreground the possibility that the emergence of symbolic behavior and cultural complexity was not a linear, species-exclusive development but rather a mosaic of interacting traditions and innovations. This paradigm recognizes the multifaceted nature of human evolution, where cultural traits may have diffused horizontally between populations rather than rising from a singular source.

Finally, sites like Saint-Césaire exemplify the critical importance of continuous archaeological investigation and methodological refinement. By revisiting sites with updated technologies and interdisciplinary approaches, researchers can unveil layers of previously inaccessible information, reshaping narratives about human origins. As this research progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that the story of human evolution during the Upper Paleolithic is one characterized by complexity, interaction, and cultural pluralism—painting a richer, more intricate portrait of our shared past.

Subject of Research: Prehistoric cultural diversity and symbolic behavior during the Châtelperronian period, focusing on shell beads and pigment use at La Roche-à-Pierrot, Saint-Césaire.

Article Title: Châtelperronian cultural diversity at its western limits: Shell beads and pigments from La Roche-à-Pierrot, Saint-Césaire.

News Publication Date: 22-Sep-2025.

Web References: http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2508014122

Image Credits: © S. Rigaud & L. Dayet

Keywords: Archaeology, Prehistory, Homo sapiens