In a groundbreaking multidisciplinary study, researchers have unveiled a refined understanding of ancient human migration routes shaped by dynamic sea-level changes since the Last Glacial Maximum. This research, spearheaded by Jerome Dobson, professor emeritus of geography at the University of Kansas, alongside collaborators from Italy, harnesses advanced glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA) modeling combined with archaeological and genetic datasets to reconstruct paleo-coastlines and migratory corridors connecting Africa with West Asia and the Mediterranean. The findings promise to reshape how scientists interpret early human dispersal, highlighting the significant yet overlooked submerged landscapes termed “aquaterra”—regions that were once habitable but are now submerged due to post-glacial sea-level rise.

The significance of aquaterra lies in its potential to harbor archaeological remains from eras when vast coastal plains were exposed due to lower sea levels. Dobson emphasizes that these landscapes, located around continental margins and islands, represent a crucial frontier for understanding human history but remain largely unexplored due to inundation. By refining sea-level reconstructions using sophisticated GIA simulations, the team has gone beyond simplistic topographic adjustments to account for Earth’s crustal deformation under the weight of ice sheets, thereby generating more physically and geophysically accurate paleo-coastlines. This level of precision is essential to map ancient land bridges and corridors critical for human migration out of Africa.

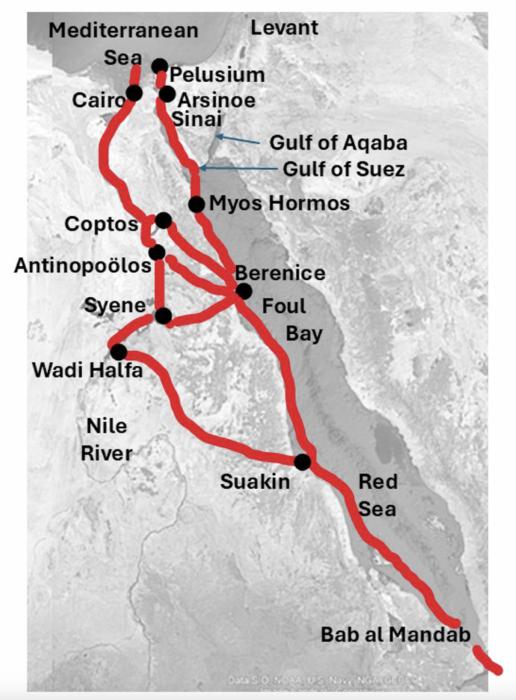

The study integrates the GIA sea-level models with DNA evidence tracing haplotype centers back nearly two million years, aligning genetic lineages with plausible geographical routes. This integrative approach reveals an ancient human haplotype hub in northeastern Sudan near Meroe in Kush, corroborating genetic data suggesting a southern African origin for Homo sapiens. Such correlations offer compelling evidence that early humans utilized multiple migratory pathways, including northern routes through the Sinai Peninsula and southern routes crossing the Red Sea at the Bab el-Mandeb strait. The research challenges previous assumptions by suggesting that some traditionally emphasized passages may have been less traversed due to natural barriers, while alternative routes like the one involving Foul Bay deserve increased scrutiny.

Foul Bay, a region on Egypt’s Red Sea coast near the ancient city of Berenice, emerges from this study as a potentially vital migratory waypoint. The researchers argue that Foul Bay constitutes a more manageable crossing point than the extensive Isthmus of Suez, which spans over 500 kilometers and would have posed immense logistical challenges to early humans. Moreover, the coral reefs and complex marine topography around Foul Bay might have both constrained and shaped human movement, offering unique ecological niches and potential markers for ancient navigational routes. Dobson advocates for further underwater archaeological exploration in these submerged reef systems, proposing that these sites may harbor physical evidence of prehistoric human activity.

Central to this renewed understanding is the acknowledgment that sea-level fluctuations following the Last Glacial Maximum, approximately 21,000 years ago, dramatically remodeled coastal landscapes. Melting ice sheets caused regional variability in sea-level rise and crustal rebound, factors meticulously captured by the team’s enhanced GIA model. This may have exposed key migration corridors for extended periods previously unrecognized, thereby altering timelines and models for human dispersal. These results underscore the necessity of employing geophysically informed models when reconstructing paleoenvironments, as reliance on simplistic sea-level subtraction methods could lead to significant misinterpretations of accessible land during critical periods of human evolution.

The team also integrates archaeological data showing limited evidence supporting the southern route across Bab el-Mandeb, a narrow passage connecting Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, now commonly presumed to be a principal migration corridor. According to Dobson, the archaeological literature reflects sparse connections between populations on either side of this divide, conflicting with genetic narratives that underscore northern pathways through Sinai as more robustly supported. This contrast invites a reassessment of migration models that favor this southern strait, highlighting the complexity and regional variation in human dispersal mechanisms.

Moreover, the Red Sea’s unique environmental conditions, including intense coral reef growth and treacherous marine currents, likely influenced navigational choices for early humans. The western side’s dense coral formations may have presented formidable natural obstacles, potentially motivating the utilization of alternative passages like those involving Foul Bay or the island chains between Sicily and the Messina straits. Dobson’s study probes these hypotheses by reconstructing ancient shorelines and marine barriers with a level of detail that could recalibrate the understanding of human migration within the context of evolving geography and environment.

Beyond hominin migration, these reconstructions hold profound implications for several scientific disciplines, including archaeology, geography, climate science, and conservation biology. Because the GIA datasets and mapping tools developed by the research team are openly accessible, they equip scholars worldwide with the capacity to examine their regions of interest through this refined lens. This democratization of data encourages interdisciplinary collaboration aimed at unraveling the complexities of human history and environmental change in coastal ecosystems over tens of millennia.

The publication of this research in the prestigious Comptes Rendus Géoscience journal cements its credibility within the scientific community. As an heir to centuries-old academic traditions, this platform highlights the interdisciplinary and international nature of the study, bridging geological, anthropological, and genetic scholarship. The involvement of esteemed institutions across continents corroborates the global significance of refining paleoenvironmental reconstructions to address enduring questions about human origins and adaptations.

Ultimately, Dobson’s work advocates a paradigm shift in paleoanthropological research by prioritizing submerged landscapes as critical repositories of human history. He urges the scientific community to harness these insights to direct future fieldwork toward these elusive aquatic terrains, which have remained out of reach for conventional archaeological techniques. The notion that vast archaeological treasures lie beneath modern seas provokes excitement and calls for innovation in underwater technology and survey methodologies. This pioneering research thereby paves the way for transformative discoveries about early human migrations and environmental interactions.

In summary, the integration of state-of-the-art GIA sea-level modeling with genetic and archaeological data presents a compelling narrative that redefines ancient human migratory pathways. By highlighting the dynamic interplay between glaciation, crustal deformation, sea-level rise, and human dispersal, this study enriches the scientific understanding of our species’ epic journey. The uncovering of aquaterra zones and reevaluation of migration corridors like Foul Bay promise to inform and inspire myriad future investigations into humanity’s deep past, fostering a holistic perspective on how environmental processes and human agency co-evolved in shaping civilization.

Subject of Research: Ancient human migration routes, sea-level change, glacial isostatic adjustment, paleo-coastlines, archaeological and genetic integration

Article Title: Not explicitly provided in the text

News Publication Date: Not explicitly provided in the text

Web References:

- https://www.eurekalert.org/multimedia/1083770

- https://dx.doi.org/10.5802/crgeos.273

- https://news.ku.edu/news/article/2014/06/16/researcher-calls-attention-vast-overlooked-zone-called-aquaterra

References:

Dobson, J., Spada, G., & Galassi, G. (Year unspecified). Ancient human demography across Africa and West Asia reconstructed from GIA-modeled sea-level changes and DNA data. Comptes Rendus Géoscience. DOI: 10.5802/crgeos.273

Image Credits: Dobson et al

Keywords: Human migration, aquaterra, glacial isostatic adjustment, Last Glacial Maximum, sea-level change, paleo-coastlines, archaeology, genetics, Red Sea, Foul Bay, Nile Valley, Pleistocene