Ancient cooking implements reveal vital insights into early human diets at archaeological sites, particularly the bedrock metates of the western United States. These large, flat stones have stood the test of time, providing archaeologists with an unprecedented opportunity to delve deep into the dietary practices of ancestral peoples. This research is being spearheaded by scientists based at the Natural History Museum of Utah. Their innovative application of modern techniques to extract microscopic plant residues promises a wealth of information about the flora that sustained Indigenous communities for millennia.

The metate, a staple of pre-Columbian cooking, transforms simple raw ingredients into culinary treasures through the grinding process. Traditionally, a mano, or handheld stone grinder, is employed alongside a metate, which can be either a freestanding slab or a depression carved into bedrock. Evidence suggests that these functional tools have been utilized for over 15,000 years—a testament to their value in food preparation. However, it is in the detailed examination of these tools that scientists hope to uncover stories of survival, adaptation, and resilience among ancient populations.

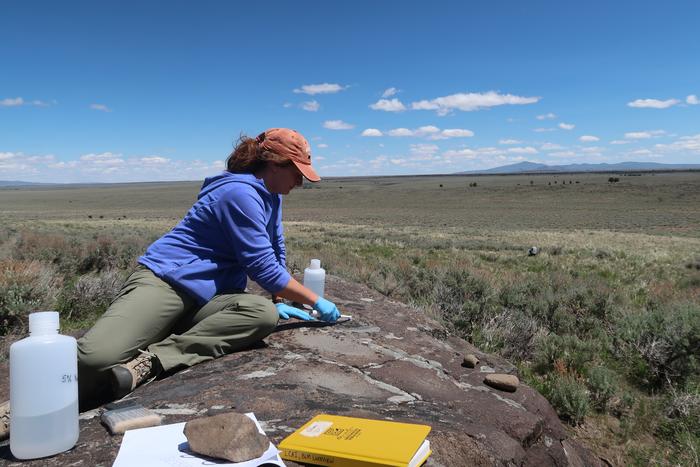

Among the leading researchers pursuing this objective is Stefania Wilks, an archaeobotanist currently based at the University of Utah. Wilks, along with her mentor and NHMU’s Curator of Archaeology, Lisbeth Louderback, is committed to exploring how people interacted with their environment through plant processing. By analyzing starch granules retrieved from the crevices of bedrock metates, the team is illuminating a previously obscured aspect of prehistoric life.

The research process begins with the collection of potentially significant residues. Wilks and Louderback meticulously isolate granules from the surface of bedrock metates, employing an electric toothbrush as a non-destructive extraction tool. However, the true treasures lie deeper within the stone’s cracks—those inaccessible nooks that have preserved plant remains over thousands of years. Using a deflocculant to liberate small particles from the stone, the team can obtain samples that provide a clearer picture of the plants indigenous communities relied on.

In their microscopic examinations, the researchers found a striking disparity between the starch granules present on the metate surfaces and those found embedded in the stone. While the surface samples yielded little to no granules, the deep crevices revealed a trove of starch traces. This key finding validates the hypothesis that ancient peoples used bedrock metates specifically for grinding various plants, highlighting the importance of these structures in their relentless quest for sustenance.

As they refined their methodology, Wilks and Louderback engaged in a painstaking process of identifying the species represented by their findings. This involved analyzing the morphology of hundreds of starch granules, allowing the researchers to create a comparative database with granules from plants that still exist today. This endeavor was not merely academic; it was a linking of past and present, showcasing the enduring significance of certain flora to local Indigenous groups.

Among the noteworthy discoveries, members of the carrot family appeared prominently, with a special focus on biscuit root. Additionally, remnants of wild grasses, particularly wild rye, emerged from the analysis, underscoring the vital role these plants played in the diets of early inhabitants of the region. The findings established essential connections between the identified plants and the traditional food sources utilized by Indigenous cultures, emphasizing the continuity of cultural practices surrounding food preparation.

The significance of this research extends beyond the mere identification of plant taxa. It exposes a complex and rich tapestry of human interaction with the environment, showcasing how early peoples adapted to their surroundings and harvested natural resources sustainably. Understanding how they processed these plants provides critical insights into their diets, health, and lifestyle, while also illustrating how environmental changes may have influenced their practices over time.

One of the challenges faced by the researchers lies in the ephemeral nature of certain plant parts in the archaeological record. Many vegetables and roots decompose quickly, leaving little evidence for study. However, the analysis of starch granules now offers a vital alternative avenue for exploring historic dietary practices. This groundbreaking approach paves the way for further studies concerning the relationships between ancient peoples and their botanical resources, opening new doors to understanding how these interactions shaped cultural and physical landscapes.

Bedrock metates, often relegated to the background in archaeological narratives, deserve recognition for their invaluable contribution to our understanding of ancient human lifeways. These structures are both rugged and unassuming, but they contain rich stories waiting to be told. Each crevice may hold a different narrative of cultural significance, and as the researchers continue their work, they are shedding light on these overlooked artifacts and the deep-rooted histories they encapsulate.

The implications of this research resonate well beyond the confines of academic archaeology. For Indigenous communities, the connections to traditional food practices and the environmental stewardship embedded in these findings are profound. Recognizing the historical significance of local flora not only honors ancestral knowledge but also contributes to ongoing efforts to revive and sustain traditional agricultural practices. As these links between the past and present are forged, the research stands as a powerful reminder of the intricate relationships between people and plants.

As the Natural History Museum of Utah moves forward with its research, the findings will undoubtedly contribute to a more nuanced understanding of early human diets across North America. Bridging the gaps between archaeology, botany, and anthropology, this study exemplifies the value of interdisciplinary collaboration in uncovering the complexities of human history. By placing this important information in a broader context, the researchers advocate for a greater appreciation of our shared heritage and the myriad ways that ancient practices continue to influence the present.

In summary, the innovative approaches taken by Wilks, Louderback, and their team have revealed the hidden stories of bedrock metates and their role in ancient food processing. As they continue to delve deeper into these fascinating artifacts, the research stands poised to redefine our understanding of what it meant to thrive in prehistoric landscapes. Each granule extracted is not just evidence of past diets, but a thread that weaves together the lives of countless individuals who have come before us, reminding us of the intricate connections we share with our environment and each other.

Subject of Research: Microscopic plant residues from bedrock metates

Article Title: Starch Granule Evidence for Biscuitroot (Lomatium spp.) Processing at Upland Rock Art Sites in Warner Valley, Oregon

News Publication Date: 11-Feb-2025

Web References: https://nhmu.utah.edu/science/collections/archaeology

References: Cambridge University Press, American Antiquity

Image Credits: Stefania Wilks, University of Utah

Keywords: Archaeology, Ethnobotany, Anthropology, Human Diets, Food Processing, Indigenous Practices, Starch Analysis, Bedrock Metates